“In Damascus the ethnarch under Aretas the king was guarding the city of the Damascenes in order to seize me…” (2 Cor. 11:32 NASB).

In our next bioarchaeography, we’ll be archaeology to explore the life of the Nabataean king, Aretas IV. He is only mentioned once in the Bible in connection with the apostle Paul’s escape from Damascus. He is also indirectly involved in the drama surrounding John the Baptist’s death, as the prophet had publicly criticized Herod Antipas for divorcing his first wife, the daughter of Aretas, to marry Herodias (Lk 3:19).

The Nabataeans

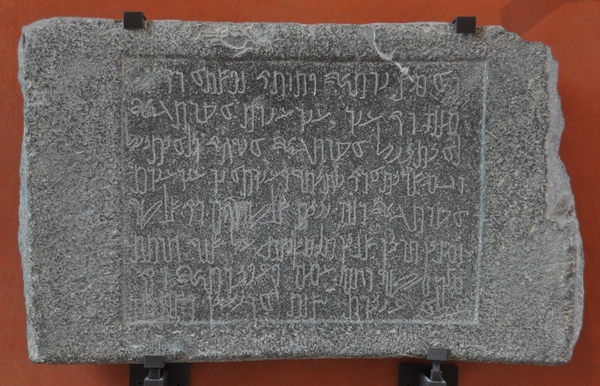

There is no known ancient written history of the Nabataeans. They are first mentioned by the first-century BC writer, Diodorus of Siculus (Bibliotheca Historica, 19.94:1–10), who based his information on the writings of the fourth-century BC writer, Hieronymus. of Cardia (ca. 360–260 BCE).1 By the second century BC, an independent Nabataean kingdom had emerged, indicated by the fact that they began minting their own coins.2 They were known for inhabiting the arid region east of the Jordan River (in modern-day Jordan) and became wealthy through their trade of frankincense, myrrh, and spices. Most of what is known about the Nabataeans comes from scattered comments by ancient writers, archaeological evidence (ie. architecture and limited inscriptions), and from numismatics.

Aretas IV’s Rise to Power

When the Nabataean king Obodas III (ca. 30–9 BC) died the kingdom was plunged into a period of political turmoil. Aeneas claimed the throne at Petra and changed his name to Aretas (IV); he immediately sent an envoy to Caesar Augustus hoping to be recognized as the new ruler.3 Augustus was angry with Aretas for taking the kingdom without first seeking his approval and instead recognized Syllaeus, an important official in the court of Obodas, as the king.4 Aretas accused Syllaeus of poisoning Obodas, being financially irresponsible, and committing adultery with many Roman women. An envoy of Herod the Great also accused Syllaeus of these things and of being the cause a rift between Caesar and himself.5 Caesar Augustus eventually condemned Syllaeus to death and reluctantly acknowledged Aretas as king of Nabataea. Aretas reigned for over 40 years (ca. 9 BC–40 AD), and brought both relative stability and economic prosperity to the Nabataean kingdom.

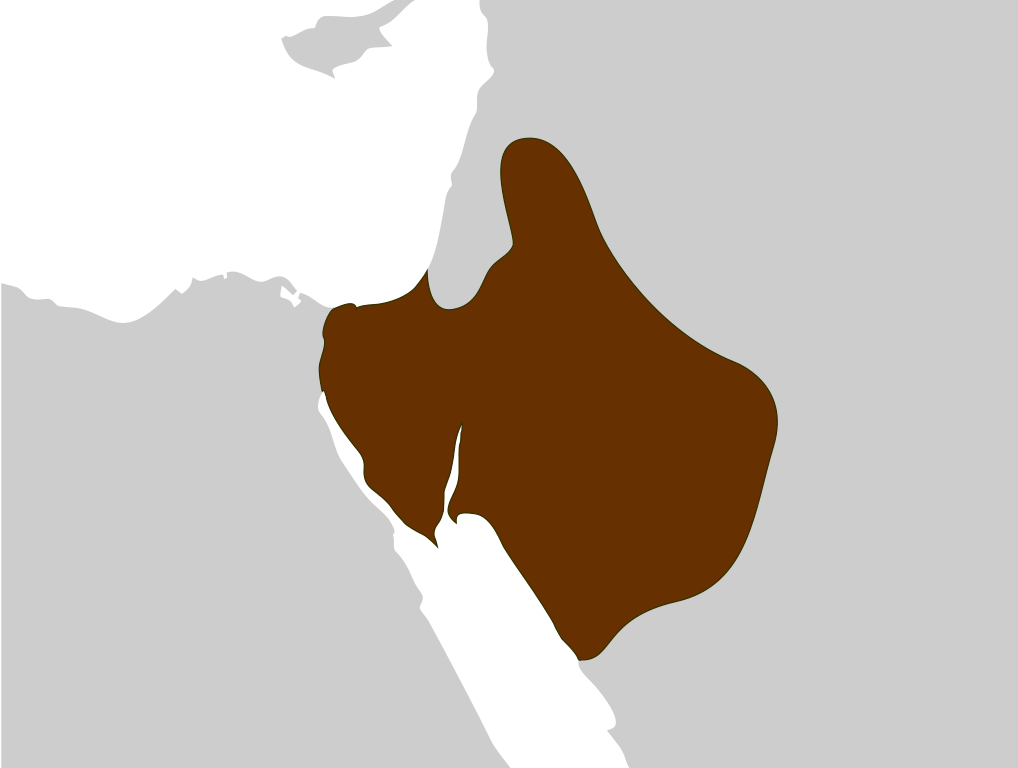

Aretas IV’s Kingdom

Under Aretas’s rule, the Nabataean kingdom continued to expand their vast trading network, setting up merchant ports in far away places, such as at Alexandria, Egypt and Peteoli in modern-day Italy. They also controlled the Silk Road, the Frankincense Road, and the King’s Highway, along with maritime trade routes in modern-day India and Sri Lanka.6 This allowed the Nabataeans to become a major economic power in the first century.

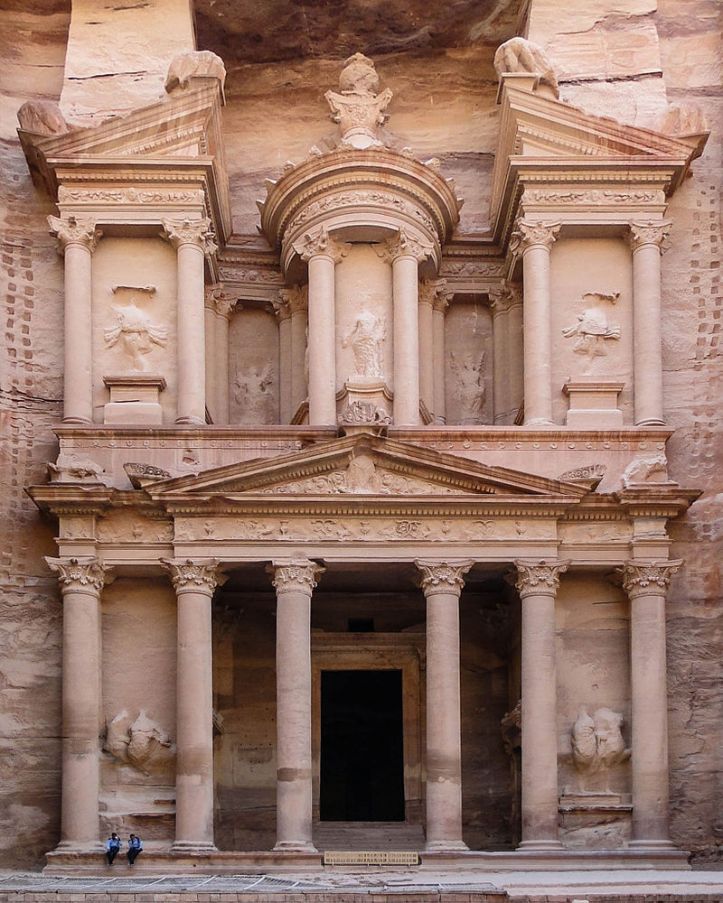

The Nabataean city of Petra grew during the reign of Aretas with many of the monumental structures attributed to this period, including the construction of the theater.7 Excavations in 1973 revealed a temple dedicated to the Nabataean god Dhu-Shara (“Lord of the Shara Mountain”), which was built by Aretas.8 Many scholars believe the Khazneh/Treasury, the massive rock-carved façade popularized by the 1989 movie, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, was the tomb of Aretas.9

The Nabataean culture reached its height under Aretas IV’s rule. According to the Anchor Bible Dictionary, “Their distinctive art, architecture, pottery, and peculiar Aramaic script all developed their classical style during his reign.”10

Aretas IV’s Coins

According to Rachel Barkay, a numismatics teacher at the Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem: “Aretas IV was the most prolific of the Nabataean kings, minting the greatest variety and quantity of coins, in silver, bronze and lead, in the course of his 48 years in power…Aretas IV’s dated coins cover 75% of his 48years in reign; most of these are silver sela‘in.”11 Many of his coins bear the title, “Aretas, king of the Nabataeans, the lover of his people.” Aretas is known to have had two queens, who are often depicted on his coins: Huldu, from years 1-24, and Shuqailat, from years 26-48.12

Aretas IV and Herod Antipas

Aretas formed an alliance with Herod Antipas by giving his daughter, Phasaelis, as his wife. However, when Antipas visited Rome, he stayed with his step-brother, Herod Philip I, and fell in love with his wife, Herodias. Both Antipas and Herodias agreed to divorce their spouses to marry each other. When Phasaelis discovered the plan, she fled to her father, who raised the army. According to Josephus, “When they had joined battel all Herod’s army was destroyed”13 Herod Antipas married Herodias nonetheless, and faced sharp criticism from John the Baptist for this. Herod responded by imprisoning and eventually executing the prophet at the request of Herodias’ dancing daughter (Mt 14:1-12).

Aretas IV’s Ethnarch in Damascus

The apostle Paul’s mention of “the ethnarch under Aretas” in Damascus has cause no shortage of discussion. Some critics point out that, since there is no known Nabataean control of Damascus during Aretas’s reign, Paul was mistaken. Others have tried to suggest that the word ethnarch means something other than what it usually means, and that the ethnarch was nothing more than an official who oversaw the Nabataean trading colony at Damascus. The sole reason for questioning a Nabataean ethnarch at Damascus seems to rest solely upon an anti-biblical bias: if there is no extra-biblical evidence for something mentioned in the Bible, it is generally doubted.

However, Jerome Murphy-O’Connor has noted, “In default of any reliable evidence to the contrary, therefore, Paul’s assertion of a Nabataean presence in Damascus prior to the death of Aretas IV must be considered trustworthy.”14 Moreover, there are good historical reasons to take the biblical text at face value.

First, there is the fact that Damascus was under Nabataean control earlier in history: In 85 BC Aretas III took control Damascus and ruled it for a dozen years.15 Damascus was an important urban center that benefited their trade network, so it is not difficult to imagine Aretas IV wanted it back under Nabataean control.

Secondly, when the Tiberius Caesar died in 37 AD, Gaius (better known as Caligula) became emperor and initiated a change in imperial policy, giving various regions to friends of Rome: In AD 37, Commagene was given to his friend Antiochus, Herod Agrippa received extended territory in the Transjordan, and the next year Ituraea was given to Sohaemus.16 In this historical context, it is entirely probable that Aretas, who had previously supported Gaius’ father Germanicu17, would have been given control of Damascus for a short time before his death.

Thirdly, Justin Taylor has shown that the Nabataean kingdom had royal officers over various districts, who were sometimes called ethnarchs.18

Thus, Paul’s comment about the ethnarch of Aretas in Damascus is both historically accurate and an important chronological marker in his life.

Conclusion

Understanding the life of Aretas IV of Damascus helps students of the Bible understand the background to two events in the New Testament: John the Baptist’s death and Paul’s escape from Damascus. Aretas’s power, wealth, and the length of his reign made him a significant figure in the first century. The vast Nabataean trade networks brought many of the things that people used in their everyday lives in the New Testament-era. Indeed, it is likely, given the virtual monopoly that the Nabataeans had on the trade of frankincense, even one of the gifts given to the child Jesus by the magi originally came from the stores of Aretas at Petra.

Cover Photo: AR Drachm of Aretas IV. Used with permission of wildwinds.com

Endnotes

1 Rachel Barkay, “Coinage of the Nabataeans.” Qedem, Vol. 58, (2019), 3.

2 Ibid, 4.

3 Josephus, Antiquities, 16.9.4.

4 David F. Graf, “Aretas,” In The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. D.N. Freedman. (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 636-637.

5 Josephus, Antiquities, 16.10.8.

6 Dan Gibson, “Nabataean Trade Routes,” Nabataea.net. Online: https://nabataea.net/explore/travel_and_trade/nabataean-trade-routes/ (Accessed June 16, 2023).

7 David F. Graf, “Aretas,” In The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. D.N. Freedman. (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 637.

8 Philip C. Hammond, “New Light on the Nabataeans.” Biblical Archaeology Review 7:2 (March/April 1981), 33.

9 Avraham Negev, “Understanding the Nabateans.” Biblical Archaeology Review 14:6 (November/December 1988), 34.

10 David F. Graf, “Aretas,” In The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. D.N. Freedman. (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 637.

11 Rachel Barkay, “Coinage of the Nabataeans.” Qedem, Vol. 58, (2019), 45.

12 Ibid, 46.

13 Josephus, Antiquities, 18.5.1.

14 Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, Paul A Critical Life. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 6.

15 Dan Gibson, “The History of Nabataea.” Nabataea.net. Online: https://nabataea.net/explore/history/history/ (Accessed June 19, 2023).

16 Robert Jewett, A Chronology of Paul’s Life. (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1979), 32

17 Ibid, 33.

18 Justin Taylor, “The Ethnarch of King Aretas at Damascus: A Note on 2 Cor 11, 32-33.” Revue Biblique, Vol. 99, No. 4, (October 1992), 722-723.