I published my first archaeological biography on King Hezekiah back in 2019. Since then, I have had a goal to publish an article on every Hebrew king directly attested in extra-biblical historical sources.1 With this blog on Ahaziah, King of Judah, I have completed that task. Hopefully, more inscriptional evidence for other Israelite or Judahite kings will be discovered and I will add more blogs to the list below. Until then, there are many foreign kings named in the Bible that I will write about in the future.

Here is the complete list of Hebrew kings confirmed by archaeology through extra-biblical inscriptions:

| Kings of Judah | Kings of Israel |

| David (ca. 1009 – 969 BC)2 | Omri (ca. 885-874 BC) |

| Ahaziah (ca. 841 BC) | Ahab (ca. 874 – 853 BC) |

| Uzziah (ca. 767 – 740 BC) | Jehoram (ca. 852 – 841 BC) |

| Ahaz (ca. 732 – 716 BC) | Jehu (ca. 841 – 814 BC) |

| Hezekiah (ca. 716 – 687 BC) | Jehoash (ca. 798 – 782 BC) |

| Manasseh (ca. 687 – 643 BC) | Jeroboam II (ca. 782 – 753 BC) |

| Jehoiachin (ca. 598 BC) | Menahem (ca. 752 – 742 BC) |

| Pekah (ca. 752 – 732 BC) | |

| Hoshea (ca. 732 – 723 BC) |

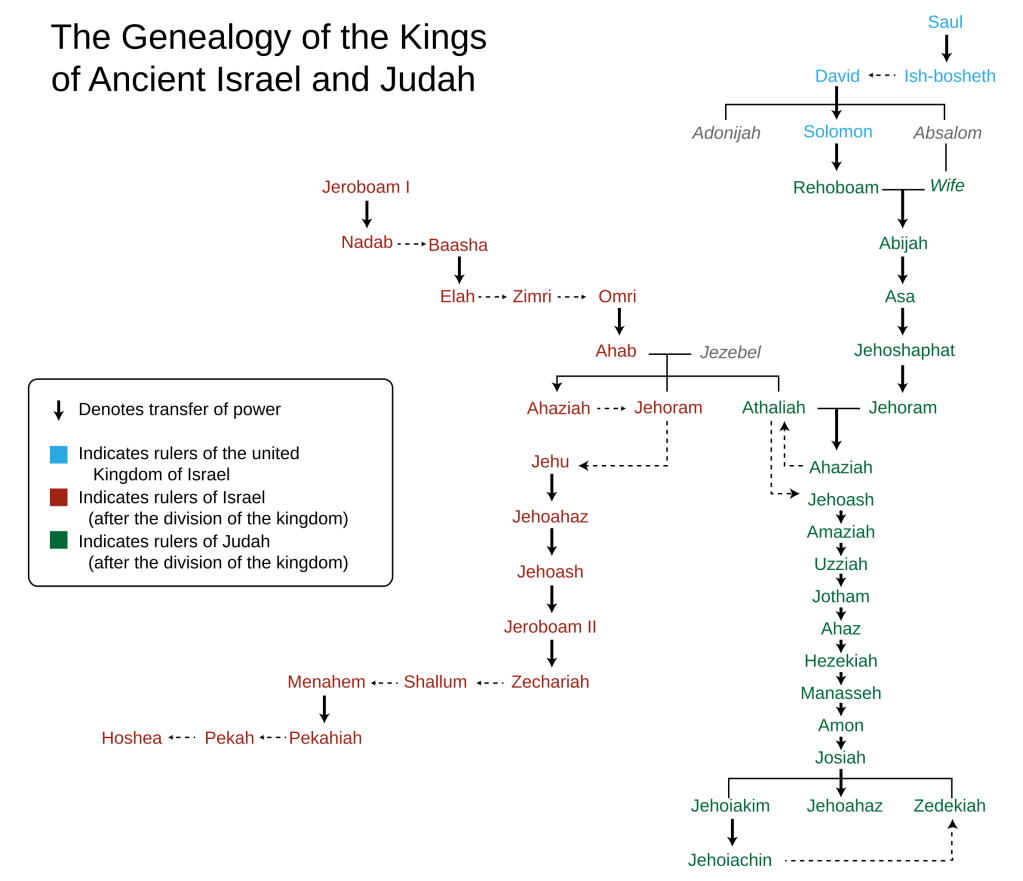

Today we’ll be using archaeology to analyze the life of Ahaziah, king of Judah (not to be confused with Ahaziah, king of Israel). Ahaziah reigned as king over Judah for only one year (ca. 841 BC). The biblical description of his reign is summarized in 2 Kings 8:25 – 29:

In the twelfth year of Joram the son of Ahab, king of Israel, Ahaziah the son of Jehoram, king of Judah, began to reign. Ahaziah was twenty-two years old when he began to reign, and he reigned one year in Jerusalem. His mother’s name was Athaliah; she was a granddaughter of Omri king of Israel. He also walked in the way of the house of Ahab and did what was evil in the sight of the LORD, as the house of Ahab had done, for he was son-in-law to the house of Ahab. He went with Joram the son of Ahab to make war against Hazael king of Syria at Ramoth-gilead, and the Syrians wounded Joram. And King Joram returned to be healed in Jezreel of the wounds that the Syrians had given him at Ramah, when he fought against Hazael king of Syria. And Ahaziah the son of Jehoram king of Judah went down to see Joram the son of Ahab in Jezreel, because he was sick.

Ahaziah’s name means, “Yahweh has taken hold [for protection]” or “whom Yahweh sustains.” In 2 Chronicles 21:17 and 25:23 he is referred to by the name Jehoahaz, a simple transposition of the component parts of the compound name.3

Jerusalem During the Reign of Ahaziah

Ahaziah reigned for only one year and would not have been able to complete any substantial building projects in so short a time. What do we know, archaeologically, about Jerusalem in the mid-ninth century BC? What did the Jerusalem that Ahaziah ruled look like? According to the New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, “Remains belonging to stratum 13 (ninth century BCE) were meager, in comparison with the remains antedating and postdating this stratum. The remains of this century must have been destroyed between the massive building activities in the tenth century BCE and the building boom during Hezekiah’s reign.”4 So there are few archaeological remains from Ahaziah’s day.

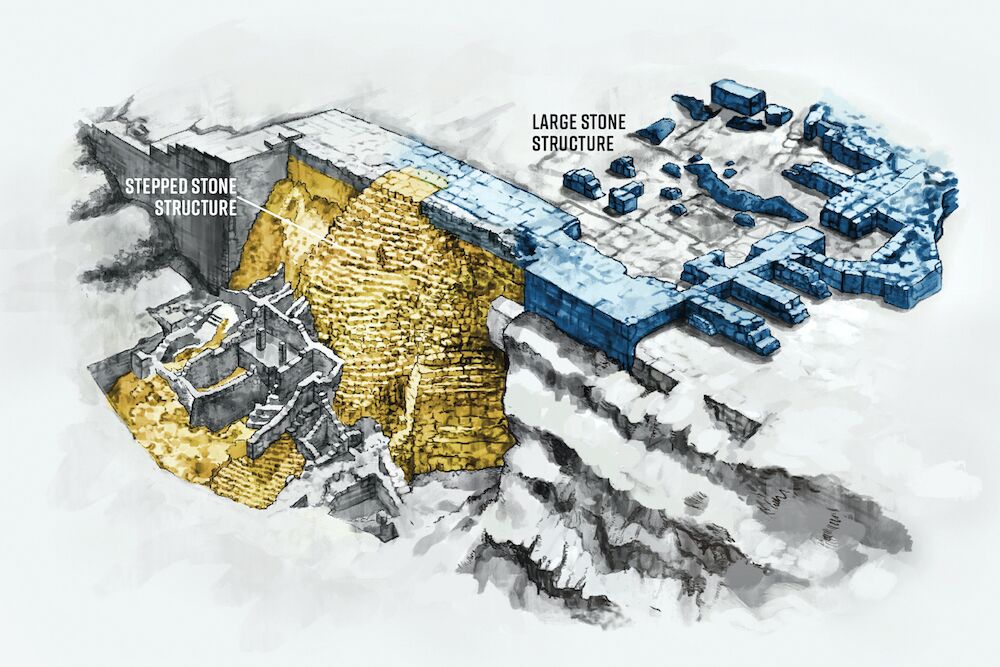

Still, several monumental structures would have been standing during Ahaziah’s reign, including the Temple, the palace complex, and the Millo. Very little remains from the First Temple, due in large part to the destruction by the Babylonians, the subsequent rebuilding of the Temple Mount, especially during the days of Herod, and the fact that excavations there today are not possible.

Potential remains of the palace complex, however, do remain, and were excavated by Eilat Mazar from 2005 – 2007. The “Large Stone Structure,” as it has been dubbed, is a monumental palatial complex constructed of impressive stones with walls that were 6-8 feet wide and having beautiful proto-Aeolic capitals. It is located above the famous Iron-Age Stepped-Stone Structure, which probably supported the Fortress of Zion and the Large Stone Structure above. Based on the dating of the pottery, the structure, which Mazar identified as the palace of King David, was likely constructed in the 10thcentury BC and underwent several renovations in two or three phases over a period of almost 200 years.5

The Millo, which stood from at least the days of Solomon (1 Kgs 9:15) to Hezekiah (2 Chr 32:5) was another monumental structure that was still standing when Ahaziah reigned. What the Millo was has been a matter of debate: Kenyon suggested it was a terrace wall she uncovered in her excavations, while others believe it was the famous Stepped Stone Structure.6 A new theory suggests the Millo, which comes from the Hebrew word meaning “to fill” refers to the fortified place where the ancient people of Jerusalem filled their water containers.7 The Spring Tower, on the eastern side of Jerusalem, was part of a fortification system that protected the Gihon Spring, and allowed the inhabitants of the city to access their water source in safety. Excavations have revealed that the Spring Tower and fortified passage to it were likely constructed by the Canaanites in the Middle Bronze Age (ca. 2000 – 1550 BC), were in use throughout much of the Iron Age, and underwent renovations during the nineth and eighth centuries BC.8

The Alliance Between Judah and Israel

Ahaziah reigned at a time when Judah was allied with Israel. When the great schism originally occurred, resulting in the formation of the northern Kingdom of Israel and the southern Kingdom of Judah, there was “there was war between Rehoboam and Jeroboam continually” (1Kgs 14:30 ESV). The hostility between the two kingdoms continued throughout the reigns of subsequent kings: “And there was war between Asa and Baasha king of Israel all their days” (1Kgs 15:16 ESV). However, during the reign of Ahaziah’s grandfather, “Jehoshaphat also made peace with the king of Israel” (1Kgs 22:44). This alliance between Israel and Judah appears to have been formalized when Jehoshaphat secured, Athaliah, the granddaughter of Omri and likely the daughter of Ahab and Jezebel, as a wife for his son Jehoram. Athaliah later became the mother of Ahaziah (2 Kgs 8:26) and may haven named him after his uncle, Ahaziah, king of Israel. Thus Ahaziah of Judah was the grandson of both Jehosaphat and Ahab, and was descended from the lines of both the kings of Judah and Israel.

Israel and Judah, now allies, fought together against Ben-Hadad King of Syria (1 Kgs 20:1; 1 Kgs 22:1-4). This alliance was short-lived, however, as Ahaziah’s grandson, Amaziah went to war against Jehoash, king of Israel, when the latter would not give a daughter to Amaziah’s son for a wife (2 Kgs 14:9-12). This battle was recently affirmed by an archaeomagnetic study of the destruction layer at Beth-Shemesh, attributing the destruction to Jehoash, King of Israel.9

Ahaziah’s Death and the Tel Dan Stele

Ahaziah’s alliance with Israel ultimately led to his downfall. The Chronicler records:

“[Ahaziah] went with Jehoram the son of Ahab king of Israel to make war against Hazael king of Syria at Ramoth-gilead. And the Syrians wounded Joram, and he returned to be healed in Jezreel of the wounds that he had received at Ramah, when he fought against Hazael king of Syria. And Ahaziah the son of Jehoram king of Judah went down to see Joram the son of Ahab in Jezreel, because he was wounded. But it was ordained by God that the downfall of Ahaziah should come about through his going to visit Joram. For when he came there, he went out with Jehoram to meet Jehu the son of Nimshi, whom the LORD had anointed to destroy the house of Ahab. And when Jehu was executing judgment on the house of Ahab, he met the princes of Judah and the sons of Ahaziah’s brothers, who attended Ahaziah, and he killed them. He searched for Ahaziah, and he was captured while hiding in Samaria, and he was brought to Jehu and put to death” (2 Chr 22:5 – 9a ESV).

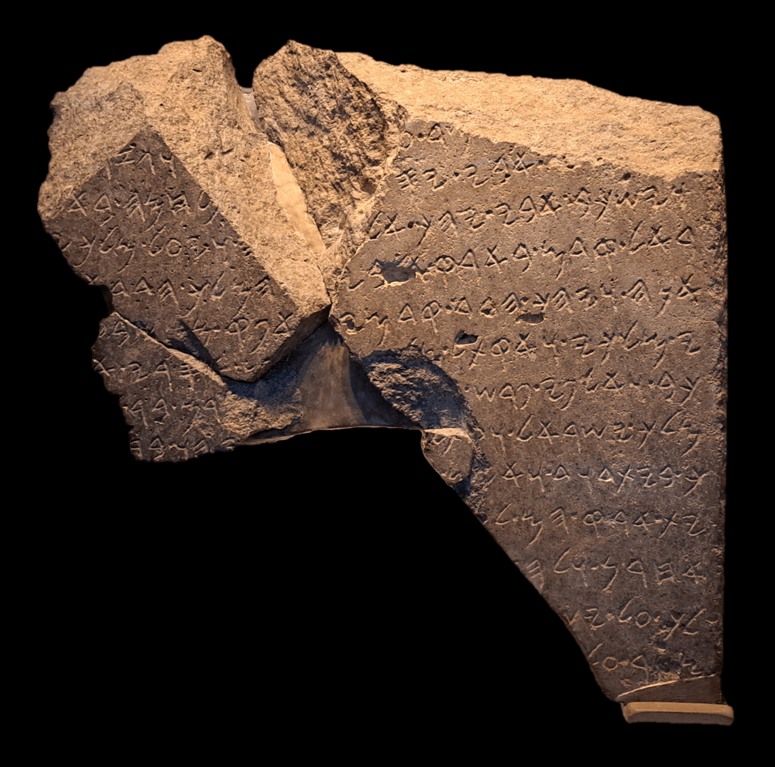

Archaeological confirmation of Ahaziah’s historicity comes from the Tel Dan Stele, a victory monument erected by an Aramean (Syrian) king, likely Hazael. It appears to reference the events surrounding Ahaziah’s death. It reads:

“And my father lay down and went to his [ancestors] and the king of I[s]rael entered previously into my father’s land. [And] Hadad made me king. And Hadad went in front of me, [and] I departed from [the] seven […]s of my kingdom, and I slew the [seve]nty kin[gs]. , who harnessed thou[sands of cha]riots and thousands of horsemen (or: horses). [I killed Jeho]ram son of [Ahab] king of Israel, and [I] killed [Ahaz]iahu son of [Jehoram kin]g of the House of David.”10

The inscription is fragmentary and only contains only the ending of the two kings who were slain: “[…]ram son of […] king of israel and “[…]iahu son of […]g of the House of David.” However it is virtually certain that it originally read, “Joram son of Ahab king of Israel” and “Ahaziahu son of Jehoram king of the House of David.” The reality is that there is only one king in the entire list of Israelite kings whose name ends with -ram: Jehoram, son of Ahab.11 And ruling at the same time was Ahaziah, son of Joram, king of Judah.

We do need to be careful to avoid circular reasoning, that is, using a biblical context to confirm a biblical person, in making these identifications.12 I recommend using Lawrence Mykytiuk’s three three-step methodology13 in order to make a positive identification. Applied to the Tel Dan Stele, he demonstrates that the inscription is: 1) Authentic; 2) Likely written by Hazael within 50 years of the events; and 3) Bears three identifying marks: the endings of the names of the kings killed matches the names of the biblical kings of Israel and Judah at this time, the kingdom they are said to have ruled over also match, and Hazael is implicitly connected to the killings of Jehoram of Israel and Ahaziah of Judah in both the biblical text and Tel Dan Stele. Based on this reasoning, he concludes, “the stele refers to these two kings with virtual certainty.”14

An explanation of the contradiction between the Tel Dan Stele’s version of history and the Bible’s is needed at this point. While Hazael claims to have killed both Jehoram of Israel and Ahaziah of Judah on the Tel Dan Stele, the Bible explicitly states that Jehu killed them. Some scholars, such as William M. Schniedewind, have explained this through an alliance between Hazael and Jehu, whereby Jehu was a vassal of Hazael. He notes a previous alliance between Damascus and Israel at the Battle of Qarqar, the connection between the rise to power of both Hazael and Jehu (1 Kgs 19:15-17), and the biblical description of Jehu later losing territory to Hazael (2 Kgs 10:32-33) as evidence.15 While this may be possible, it need not necessarily be the case. Numerous kings in antiquity took credit for the work of others. Moreover, the word translated “kill” on the Tel Dan Stele, can also mean to “strike” or “defeat.” Thus, Hazael would have had some justification for taking credit for Jehoram’s death since he was recovering from wounds he had received in battle against the Syrians when Jehu killed him.16

Conclusion

Despite reigning just one year, Ahaziah’s historicity has been confirmed by the Tel Dan Stele. Furthermore, this artifact also affirms the alliance between Israel and Judah at that time, as the rulers of both kingdoms are named as enemies of Hazael.

Title Photo of the Tel Dan Stele: יעל י / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

Endnotes:

1 I am indebted to bible scholar Lawrence Mykytiuk for his excellent research and the process he created for confirming the historicity of biblical people. Be sure to check out his article, “53 People in the Bible Confirmed Archaeologically”, available here: https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/people-cultures-in-the-bible/people-in-the-bible/50-people-in-the-bible-confirmed-archaeologically/

2 When I began writing my bioarchaeographies, I was using Edwin Thiele’s groundbreaking chronology in The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings. I have since begun to use the chronology of Roger Young, who as refined Thiele’s chronological work, fixing several minor errors. You can find his chronological tables here: https://www.rcyoung.org/CTables/frame4.html While I appreciate Roger’s quest for precision in, for example, using “931n” to represent the year beginning on Nisan 1, 931 BC and ending the day before Nisan 1, 930 BC, I will use only the year as I am writing to a non-technical audience. Further, I will only give the regnal dates for their sole reigns, as some of these kings had co-regencies with their fathers.

3 “Ahaziah,” Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary. Eds. J.D. Douglas and Merrill C. Tenney; Revised by Moises Silva. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011), 107.

4 Yigal Shiloh, “Jerusalem” in New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, Vol. 2. Ed. Ephraim Stern.(Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and Carta), p. 704.

5 Eilat Mazar, “Did I Find King David’s Palace?” Biblical Archaeology Review, January/February 2006. Online: https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-sites-places/jerusalem/did-i-find-king-davids-palace/ (Accessed Oct. 13, 2023).

6 Chris McKinny, et al. “The Millo” Jerusalem’s Lost Monument.” Biblical Archaeology Review Vol. 49, No. 3 (Fall 2023), 38.

7 McKinny, et al., 38

8 McKinney, et al., 38.

9 Ron Shaar, et all. “Archaeomagnetism in the Levant and Mesopotamia Reveals the Largest Changes in the Geomagnetic Field,” PNAS Vol. 119, No. 44 (2022), p. 4. Online: https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JB024962 (Accessed Oct. 12, 2023).

10 Avraham Biran and Joseph Naveh, “The Tel Dan Inscription: A New Fragment.” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 45, No. 1 (1995), 13. Online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27926361 (Accessed Oct. 14, 2023).

11 K. A. Kitchen, On The Reliability of the Old Testament. (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2006), 37.

12 Lawrence Mykytiuk, “Don’t Pave the Way for Circular Reasoning! A Better Way to Identify the Two Deceased Hebrew Kings in the Tel Dan Stele.” In Epigraphy, Iconography, and the Bible. Edited by Meir Lubetski and Edith Lubetski. Hebrew Bible Monographs 98. (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2021), 117.

13 Bryan Windle, “Scholar’s Chair Interview: Dr. Lawrence J. Mykytiuk.” Bible Archaeology Report. Oct. 2, 2020. Online: https://biblearchaeologyreport.com/2020/10/02/scholars-chair-interview-dr-lawrence-j-mykytiuk/ (Accessed Oct. 16, 2023).

14 Lawrence Mykytiuk, “Don’t Pave the Way for Circular Reasoning! A Better Way to Identify the Two Deceased Hebrew Kings in the Tel Dan Stele.” In Epigraphy, Iconography, and the Bible. Edited by Meir Lubetski and Edith Lubetski. Hebrew Bible Monographs 98. (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2021), 128 – 131.

15 William M. Schniedewind, “Tel Dan Stela: New Light on Aramaic and Jehu’s Revolt.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 302 (May, 1996), p. 83-85. Online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1357129 (Accessed Oct. 16, 2023)

16 Todd Bolen, “The Aramean Oppression of Israel in the Reign of Jehu,” PhD diss., (Dallas Theological Seminary, 2013), 56. https://www.academia.edu/6097624/The_Aramean_Oppression_of_Israel_in_the_Reign_of_Jehu (Accessed Oct. 16, 2023).