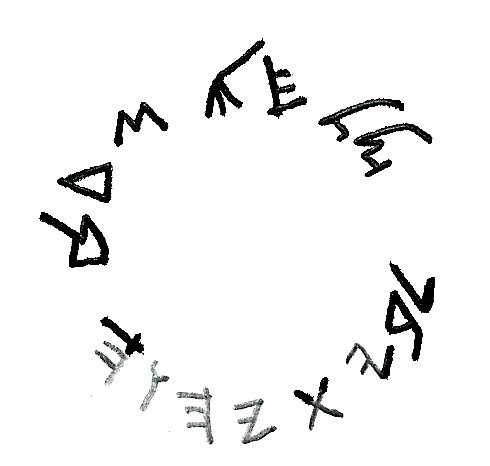

The Ivory Pomegranate is a small, pomegranate-shaped object inscribed with the words, “Belonging to the Tem[ple of the Yahwe]h, holy to the priests.”1 Some believe that it is the top of a scepter that was once used by a priest in the First Temple of Jerusalem. Others are not convinced. All scholars agree that the pomegranate itself is authentic2; however, some believe it was fraudulently inscribed in modern times.3

If authentic, this small artifact has big implications, possibly representing the only physical evidence of the First Temple in Jerusalem. If it is fake, it is a clever forgery that has fooled some of the world’s leading epigraphers and led to Israel Museum, Jerusalem (IMJ) being taken for over half a million dollars.

In this article, I will be analyzing the evidence both for and against its authenticity, and sharing what I feel is a reasonable verdict. I am not an epigrapher, nor have I examined the Ivory Pomegranate in person. I will merely be analyzing the arguments made by scholars on opposing sides that I found to be the most persuasive and sharing my opinion of its authenticity.

Timeline of Events

Before beginning, it is helpful to review the timeline of events related to the Ivory Pomegranate.4

1979 – André Lemaire sees the Ivory Pomegranate for the first time in the shop of an antiquities dealer in Jerusalem

1981 – Lemaire publishes a journal article in French outlining the evidence for the authenticity of the artifact5

1984 – Lemaire publishes a popular article in the magazine Biblical Archaeology Review on the Ivory Pomegranate6

1988 – The IMJ pays $550,000 USD for the Ivory Pomegranate after it had been authenticated by the esteemed Nahman Avigad. The funds to purchase the artifact come from an unsolicited gift to the IMJ.

1990 – Nahman Avigad publishes an article in The Biblical Archaeologist outlining the evidence for the authenticity of the Ivory Pomegranate7

2004 – The IMJ announces that, after further investigation by a team of scholars, the Ivory Pomegranate is a fake and it is removed from exhibition.8

2005-2007 – Scholars on both sides of the debate present their cases for and against the authenticity of the Ivory Pomegranate in series of articles in the Israel Exploration Journal (IEJ).9, 10, 11

2015 – Scholars examine the inscription on the Ivory Pomegranate at the IMJ again under a microscope and determine that the inscription was cut by the old break on the back of the artifact, indicating that the inscription itself is ancient as well (more on this below).12

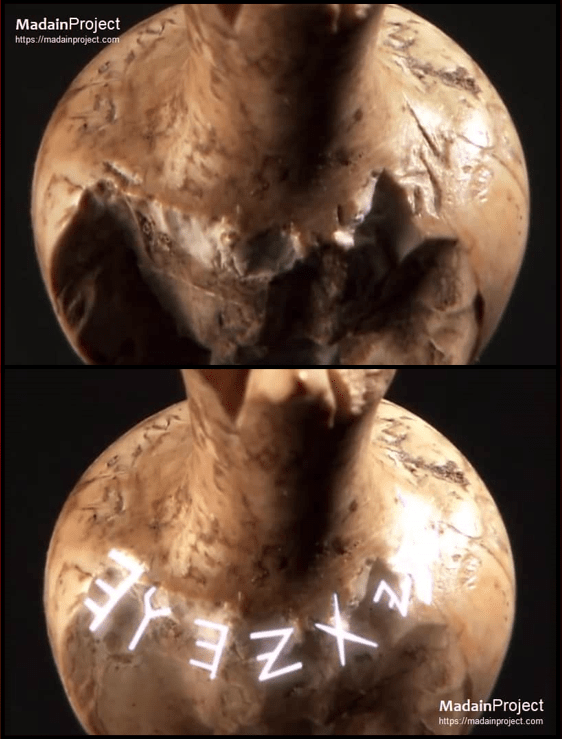

The Artifact

The Ivory Pomegranate is actually carved out of a hippopotamus tooth, and is 1.68 in./43 mm in height and .83 in./21 mm in diameter (basically, the size of a person’s thumb).13 It’s shaped like a pomegranate, with a central ball (called a grenade) and a thin neck that extends upward into what was once six petals, four of which remain. A paleo-Hebrew inscription wraps around the shoulder of the grenade. One side of the grenade is broken off, which is both unfortunate and fortunate. It is unfortunate because several letters of the inscription are fragmentary, having been impacted by the break. It is fortunate because this break may be the key to determining whether the inscription is authentic or not. In fact there are several breaks, both ancient and modern. As mentioned earlier, all scholars believe the pomegranate itself is an authentic ancient artifact, likely dating to the end of the Late Bronze Age (thirteenth-twelfth centuries BC) or to the Iron Age II (eighth century BC).14 Some scholars believe the letters of the inscription stop before the break, indicating that a forger stopped short of the edge of the fracture so as not to further damage the artifact. However, other scholars have observed a connection of two of the fragmentary letters with the old break, indicating they were inscribed before the break occurred which suggest the artifact is authentic.

The Evidence Against its Authenticity

In 2007, the Biblical Archaeology Society, convened the Jerusalem Forgeries Conference to discuss and debate several controversial artifacts, including the James Ossuary, the Ivory Pomegranate and the Jehoash Inscription. Prof. Aaron Demsky from Bar-Ilan University summarized four key lines of evidence that convinced him that the Ivory Pomegranate was a forgery:

- The artifact came from the antiquities market and did not have proper provenance.

- The improbability of the artifact being around for three or four hundred years before it was purportedly inscribed (assuming the pomegranate itself dates to the Late Brone Age and was supposedly inscribed in the Iron Age II period).

- There are two breaks on the pomegranate – one ancient and one modern. Demsky believes a modern forger inscribed an ancient broken artifact and caused the modern break. Moreover, he believes in several letters, the engraver stopped short of the old break because he was afraid of breaking off more of the artifact.

- There are spaces between the words, which Demsky believes acted as word dividers. He maintains this was a convention that was only used much later than the date the artifact was supposedly inscribed.15

Demsky was also part of a team of authors, along with Yuval Goren from Tel Aviv University and Shmuel Ahitu from Ben-Gurion University, who published further objections. These included the awkward syntax of the inscription and the presence of carbon-silicate glue in the patina, supposedly used by the forger to make a fake patina adhere to the artifact.16

The Evidence in Favor of its Authenticity

Andre Lemaire and the late Nahman Avigad are the two epigraphers who first authenticated the artifact. Lemaire, in particular, has presented rebuttals to most of arguments raised against the authenticity of the Ivory Pomegranate. For example, regarding the awkward syntax, Lemaire points out that the critics are critiquing Avigad’s translation, not his, which is worded exactly as that which Demsky, Goren, and Co. suggest proper syntax should dictate.17 Furthermore, the presence of a carbon-silicate glue on the artifact does not necessarily mean that it was used to affix fake patina, especially when it is well-known that restoration work was done on the object. Glue was used to reattach part of the break and a silicon spray was used as a protective coating on it.18 In fact, Amnon Rosenfeld and Shimon Ilani from the Geological Survey of Israel, Jerusalem have presented arguments that chemical makeup of the patina is what would be expected if it was retrieved from a tell somewhere and is actually evidence of its authenticity.19

Here are credible responses to Demsky’s four main objections:

- From the beginning, Lemaire says he was cautious about the Ivory Pomegranate and wary of it being a fake because it came from the antiquities market and not a controlled excavation.20 Artifacts from the antiquities market ought to be approached with the utmost of caution due to the sheer number of forgeries found there. However, coming from the antiquities market does not automatically disqualify an artifact from being authentic. For example, the Dead Sea Scrolls and the early Hezekiah bullae (all authentic) came to light through the antiquities market. The key is to approach the research of such an object with an abundance of caution. This is what Lemaire claims to have done with the Ivory Pomegranate.

- While Demsky raised the improbability of a Late Bronze Age artifact being inscribed in a later period, he was part of an authorship team that actually stated the opposite in a 2005 article in the Israel Exploration Journal: “It is theoretically possible that an Iron Age II inscription was engraved on a Late Bronze Age item; hence, this detail does not necessarily indicate that the inscription was added in modern times.”21 One must remember prized items, such as ivories and precious metals were known to have been kept for centuries and even millennia.22

- The question of whether the inscription stops short of the new or old breaks or continues into them is the key to assessing the authenticity of the artifact. Lemaire concedes: “The principal argument advanced by the authors against the authenticity of the inscription, based on this examination with a stereomicroscope, is that the engraving of certain fragmentary letters stops before reaching the old or new breaks. If true, this would be a clear indication that the engraving of the letters was made after the old and new breaks. Consequently, the inscription would be a modern forgery.”23 Is the is actually the case? It appears that it is not. Subsequent to their preliminary article in IEJ, Demsky, Goren and Ahitu (the critics), along with Lemaire (the proponent), co-authored a follow-up article after further investigation of the artifact. While they did not change their respective views, they all agreed that at least one letter formerly thought to be an indication of forgery because it stopped short of the break (the letter yod of byt) had a perfectly rational explanation and is incised as it should be.24 More importantly there is a connection between two fragmentary letters (the upper parts of the taw and the he) with the old break, implying the inscription was made before the ancient fracture of the artifact. This implies the inscription is not a modern forgery, but rather an authentic ancient inscription. In 2015, Lemaire met with Robert Deutsch, and Ada Yardeni (one of Israel’s leading paleographers) at the Israel Museum. Yardeni had previously examined the Ivory Pomegranate and could not confirm its authenticity. This time, however, she was able to see the crucial part of the stroke of the taw at the break. Yardeni admitted that she had earlier missed the proper angle to view this. She concluded, “Following my new examination of the tiny pomegranate with the microscope, I am now convinced and agree with André Lemaire that there is no reason to doubt the authenticity of the pomegranate [inscription].”27

- Lemaire has pointed out that the critics themselves note some ancient Hebrew inscriptions do not have word dividers. In fact, that there are so many examples of this, particularly with inscriptions on small objects like bullae (clay seal impressions), that the absence of word dividers is not a problem in Hebrew epigraphy. Finally, the contention that spaces were used as word dividers is incorrect, because, apart from two spaces that are explained syntactically, there are no consistent spaces between the other letters, as Lemaire demonstrates with specific measurements.28

The Verdict

In researching the Ivory Pomegranate, I read a variety of articles by scholars on both sides of the debate – more than I have cited below29 – but have chosen to focus on the arguments that I found to be the most persuasive. It seems to me that the question of the authenticity of the inscribed Ivory Pomegranate comes down to whether or not the inscription touches the ancient break or not. If it does – that is, if the break crosses the inscribed letters – then one can reasonably conclude the inscription is authentic, as it was there before the artifact was originally damaged. Lemaire’s most recent work has convinced some leading epigraphers that this is indeed the case for at least two of the fragmentary letters. Because the object in question was not discovered in a controlled excavation, there will always be some doubt associated with it. However, the evidence seems to me to indicate that the Ivory Pomegranate is likely an authentic artifact from the First-Temple period.

Cover Photo: The Madain Project – https://madainproject.com/ivory_pomegranate

Endnotes:

1 André Lemaire, “Probable Head of Priestly Scepter from Solomon’s Temple Surfaces in Jerusalem.” BAR, (January/February 1984). Online: https://library.biblicalarchaeology.org/article/probable-head-of-priestly-scepter-from-solomons-temple-surfaces-in-jerusalem/ (Accessed July 12, 2024).

2 André Lemaire. “A Re-Examination of the Inscribed Pomegranate: A Rejoinder.” Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 56, no. 2, 2006, p. 167. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27927141 (Accessed July 12, 2024).

3 Yuval Goren, et al. “A Re-Examination of the Inscribed Pomegranate from the Israel Museum.” Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 55, no. 1, 2005, p. 19. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27927086 (Accessed July 12, 2024).

4 This timeline is taken largely from the following article: Hershel Shanks, “Ivory Pomegranate: Under the Microscope at the Israel Museum.” BAR. March/April 2016.

5 André Lemaire, “Une inscription paleo-hebraique sur grenade en ivoire, Revue Biblique,” Vol. 88, pp. 236–239.

6 André Lemaire, “Probable Head of Priestly Scepter from Solomon’s Temple Surfaces in Jerusalem,” BAR, January/February 1984.

7 Avigad, Nahman. “The Inscribed Pomegranate from the ‘House of the Lord.’” The Biblical Archaeologist, vol. 53, no. 3, 1990, pp. 157–66. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3210115. (Accessed 24 July 2024).

8 The Associated Press, “Solomon Relic a Fake, Museum Concludes.” NBC News. Dec. 24, 2004. https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna6753063 (Accessed July 24, 2024).

9 Yuval Goren et al., “A Re-Examination of the Inscribed Ivory Pomegranate from the Israel Museum,” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 55, 2005, p. 3. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27927086 (Accessed 24 July 2024).

10 André Lemaire, “A Re-examination of the Inscribed Pomegranate: A Rejoinder,” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 56, 2006, p. 167 http://www.jstor.org/stable/27927141 (Accessed 24 July 2024).

11 Aḥituv, Shmuel, et al. “The Inscribed Pomegranate from the Israel Museum Examined Again.” Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 57, no. 1, 2007, pp. 87–95. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27927158 (Accessed 24 July 2024).

12 Hershel Shanks, “Ivory Pomegranate: Under the Microscope at the Israel Museum.” BAR. March/April 2016.

13 Yuval Goren et al., “A Re-Examination of the Inscribed Ivory Pomegranate from the Israel Museum,” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 55, 2005, p. 3. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27927086 (Accessed 24 July 2024).

14 André Lemaire. “A Re-Examination of the Inscribed Pomegranate: A Rejoinder.” Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 56, no. 2, 2006, p. 167. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27927141 (Accessed July 12, 2024).

15 Hershel Shanks, Jerusalem Forgery Conference: Biblical Archaeology Society Special Report

(Washington: Biblical Archaeology Society, 2007), p. 13-14.

16 André Lemaire. “A Re-Examination of the Inscribed Pomegranate: A Rejoinder.” Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 56, no. 2, 2006, p. 168. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27927141 (Accessed July 12, 2024).

17 Lemaire, 169-170.

18 Lemaire, 170 (including footnote #4).

19 Lemaire, 175-176.

20 André Lemaire, “Probable Head of Priestly Scepter from Solomon’s Temple Surfaces in Jerusalem,” BAR, January/February 1984.

21 Yuval Goren et al., “A Re-Examination of the Inscribed Ivory Pomegranate from the Israel Museum,” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 55, 2005, p. 6. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27927086 (Accessed 24 July 2024).

22 André Lemaire. “A Re-Examination of the Inscribed Pomegranate: A Rejoinder.” Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 56, no. 2, 2006, p. 167. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27927141 (Accessed July 12, 2024).

23 Lemaire, 171.

24 Aḥituv, Shmuel, et al. “The Inscribed Pomegranate from the Israel Museum Examined Again.” Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 57, no. 1, 2007, p. 92. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27927158 (Accessed 24 July 2024).

25 André Lemaire. “A Re-Examination of the Inscribed Pomegranate: A Rejoinder.” Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 56, no. 2, 2006, p. 175. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27927141 (Accessed July 12, 2024).

26 Hershel Shanks, “Ivory Pomegranate: Under the Microscope at the Israel Museum.” BAR. March/April 2016.

27 Shanks, 2016.

28 André Lemaire. “A Re-Examination of the Inscribed Pomegranate: A Rejoinder.” Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 56, no. 2, 2006, p. 169. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27927141 (Accessed July 12, 2024).

29 For example, I read Christopher Rolstons article, “The Ivory Pomegranate: The Anatomy of Probable Modern Forgery” (2015) in Epigraphy, Philology and the Hebrew Bible: Methodological Perspectives on Philological and Comparative Study of the Hebrew Bible in Honor of Jo Ann Hackett, but found his argument unconvincing. He has selectively chosen a few examples and made a general principle out of them that forgeries follow upon the heals of discoveries. Thus, since there were some articles published in the 1970’s about a few words that were also on the Ivory Pomegranate, it too follows the discovery-then-forgery pattern. This seems to me to be stretching the evidence to fit it into his pattern.