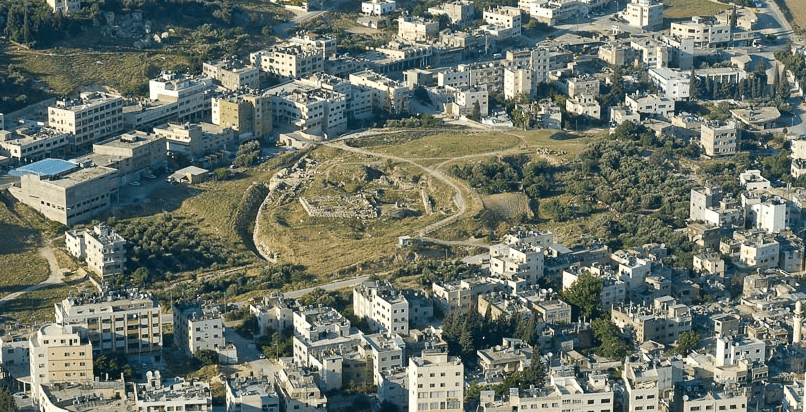

I’m beginning a new series entitled “Letters from the Biblical World.” Over the past century, numerous letters—often inscribed on cuneiform tablets—have been unearthed that appear to reference or provide background to biblical events. In this series, we’ll explore several of these collections. For the inaugural blog post, I will analyze the Amarna Letters, which were discovered at Tell el-Amarna in Egypt.

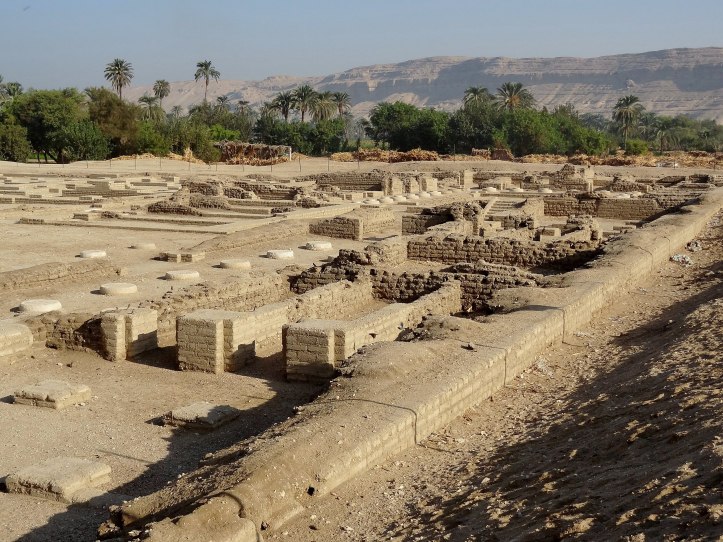

What is Tell el-Amarna?

Tell el‑Amarna is the modern name for the ruins of the ancient Egyptian city of Akhetaten (“Horizon of the Aten”). Located about 180 miles (300 km) south of Cairo, it served as Egypt’s capital for a brief period in the mid‑14th century BC.

Pharaoh Amenhotep IV, later known as Akhenaten (“Effective for the Aten”), abandoned the traditional worship of Egypt’s many gods and goddesses and dedicated himself instead to the sole worship of the Aten, the sun’s disk.

There is ongoing debate over the exact dates of Akhenaten’s reign, depending on whether one follows the high or low Egyptian chronology. According to Egyptologist Charles Aling, Akhenaten ruled from 1354–1337 BC¹ (high chronology), while Egyptologist Ian Shaw places his reign at 1352–1336 BC² (low chronology)³. Because Akhenaten’s son, Tutankhamun, later moved the capital back to Thebes, the city of Akhetaten was effectively a one‑generation capital, existing only during Akhenaten’s reign.

According to Anson Rainey, when the royal entourage moved to the new capital of Akhetaten, the scribes brought with them some letters from the archive of Amenhotep III, Akhenaten’s father, who had since died, which they felt were important. By the time the site was abandoned during the reign of Tutankhamen, a large collection of letters from the reign of Akhenaten, which were deemed obsolete, were discarded and left behind.4 This collection of letters, discovered in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, has come to be known as the Amarna Letters.

What Are the Amarna Letters?

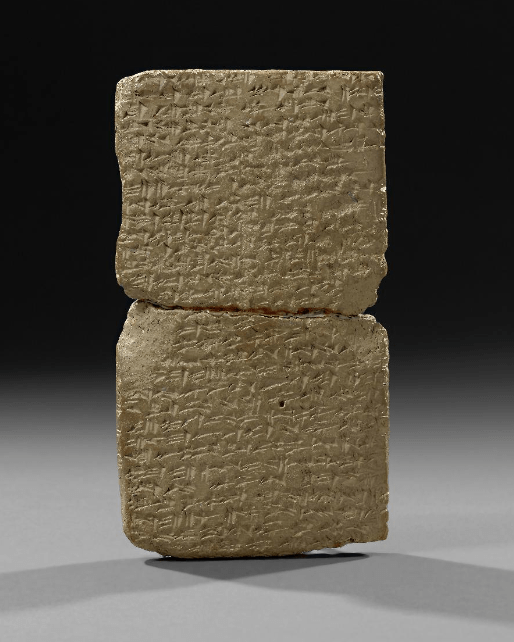

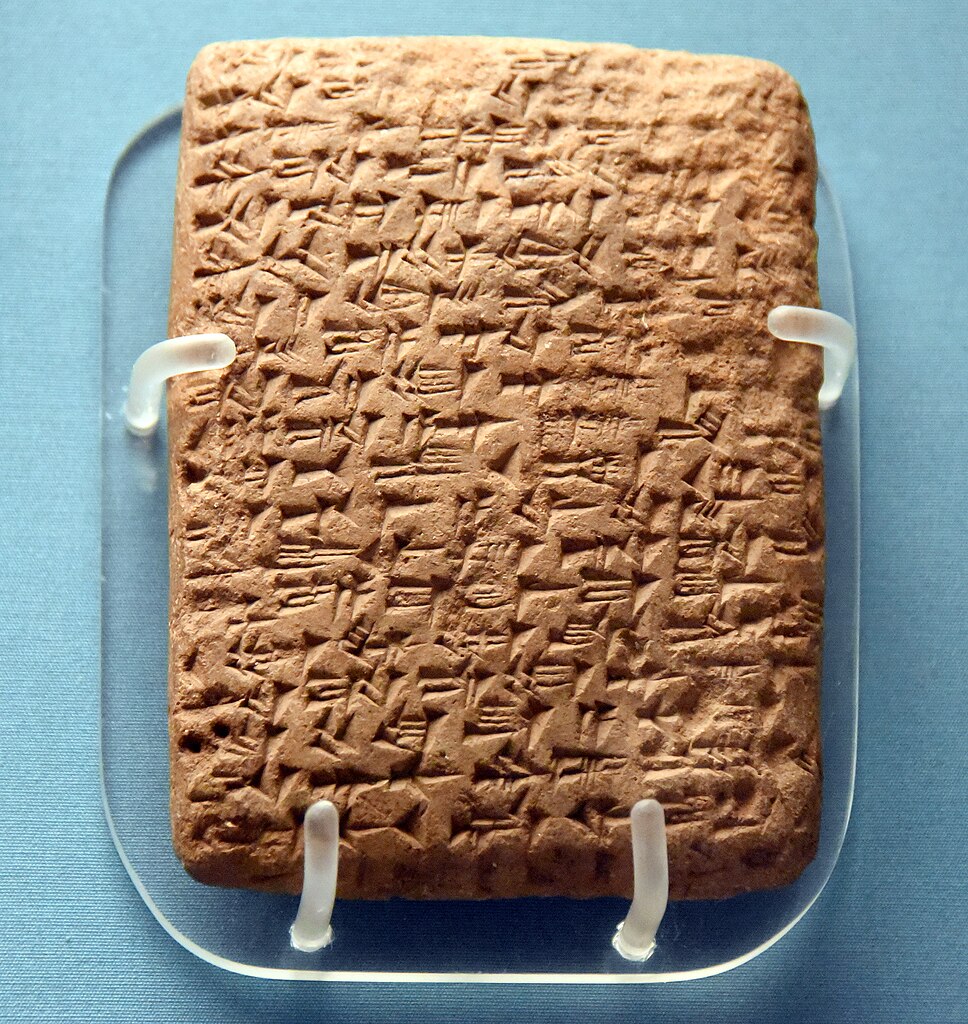

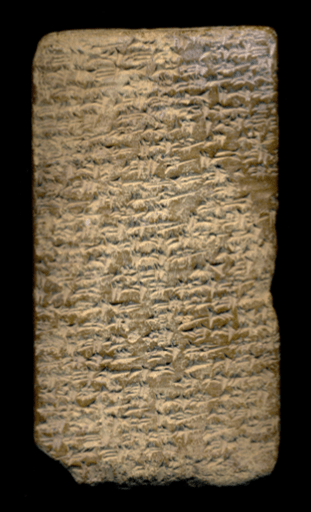

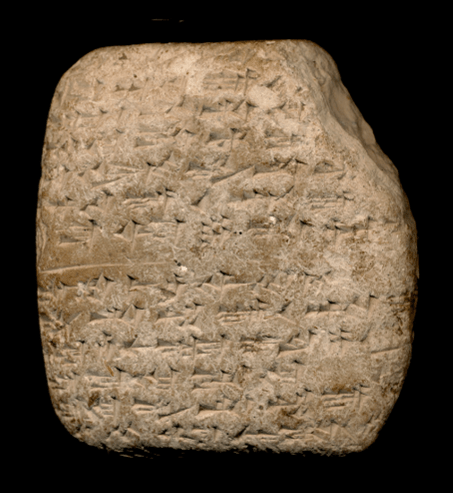

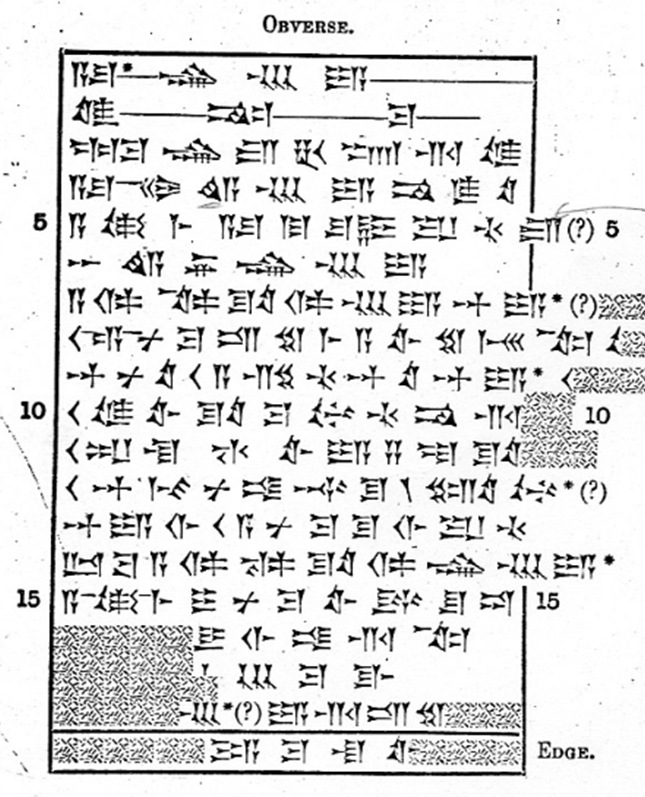

The Amarna tablets are a collection of 382 letters from the royal archives of the pharaohs Amenhotep III and Akhenaten, which were discovered at Tell el-Amarna, near a structure with bricks bearing the inscription, “The place of the letters of the Pharaoh.”5 They are official dispatches from kings as far away as the kingdom of Hatti (in modern-day Turkey) and Babylonia (in modern-day Iraq). One group of letters comes from the heads of the Canaanite city-states, which were under Egyptian control.6 Scholars can sometimes identify which letters were addressed to Amenhotep III and which were addressed to Akhenaten, based upon whether the concluding formula of the sender mentions the god Amon or not; those that do were written during Amenhotep III’s reign, and those that do not, were likely written during Akhenaten’s reign, when he had abandoned the traditional gods of Egypt.7 Each of the 382 letters are designated with an identifying code, such as EA282 (el-Amarna #282).

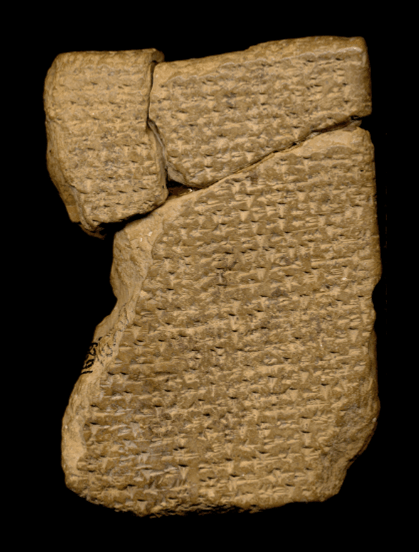

ḫa-bi-ru are taking the cities. Photo: State Museums of Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum / Olaf M. Teßmer / CC BY-SA 4.0

The Amarna Letters illuminate the geo-political situation in Canaan in the mid-14th century BC8, the period after the initial conquest battles, as Israel was establishing a presence in the land.9 Within these letters, the heads of the Canaanite city-states seek to present themselves in the most favorable light to Pharaoh, request what they lack—often Egyptian troops for defense—and report the suspected treasonous schemes of rival rulers. In some of these letters, heads of the Canaanite city-states call for help from the king of Egypt against a group or groups identified as the ʿapîru, or in the case of the letters from the king of Jerusalem, the ḫa-bi-ru.10 The ʿapîru/ḫa-bi-ru are mentioned in other ancient texts, from the UR III period to the 20th Egyptian Dynasty (roughly 800 years). The term is primarily used as a sociological designation for “marauding nomads”11 or “bands of brigands.”12 While an earlier generation of scholars tried to make an etymological link between the word ḫa-bi-ru and the term Hebrews, the term ʿapîru/ḫa-bi-ru is not usually used as an ethnic designation. The rulers of the Canaanite city-states would have surely seen the Israelites who invaded Canaan as ʿapîru/ḫa-bi-ru, a band of marauding nomads or brigands. While not every mention of the ʿapîru/ḫa-bi-ru in the Amarna letters necessarily refers to the Hebrews, the ones that refer to ʿapîru/ḫa-bi-ru in the central highlands, where the Israelites initially settled, likely do.13 At the same time, the Amarna letters indicate there were other bands of ʿapîru/ḫa-bi-ru, besides the Israelites, who were attacking Canaanite cities during the 14th century. It was a period of great upheaval for those living in the land of Canaan.

How do the Amarna Letters Relate to Biblical History?

The description of Canaan in both the Amarna letters and the Bible aligns in several striking ways:

- While the Canaanite city-states are under Egyptian control during this period, they also have some level of autonomy. For example, in EA366, Shuwardata of Hebron writes to Pharaoh that he and Abdi-Heba of Jerusalem have formed an alliance against the ʿapîru/ḫa-bi-ru (for comparison, see Josh. 10:3, where Jerusalem and Hebron are allied against the Israelites). S. Douglas Waterhouse notes, “As in Joshua’s Canaan, the Amarna texts speak of independent city-states who possess the freedom to form their own alliances and pursue their own local agendas (though they owed nominal allegiance to Egypt).”14

- According to the Amarna Letters, the rulers of the Canaanite city-states appear to be known within Canaanite society as kings (EA147:67; EA148:40–41; EA197:13–14; EA 227:3; EA256:8), just as they are in the Book of Joshua, and the phrase “kings of Canaan” is to be found in both the Bible (Jdg 5:19) and the Amarna Letters (EA 30:1; 109:46).15

- It is somewhat surprising that the Israelites appear to have encountered no Egyptian troops during their conquest battles. Similarly, the Amarna Letters seem to indicate there were few or no Egyptian troops left in the region, despite it being under Egyptian control. For example, Rib-Addi of Byblos declares, “I have repeatedly written for garrison troops but they have not been given and the king, my lord, has not heeded the words of his servant” (EA137).16 One plausible explanation for this is that, after the entire northern army was destroyed while trying to chase the Israelites through the Red Sea a generation earlier, Egyptian troops had been withdrawn from Canaan to reform an army to defend the northern border of Egypt.

The most obvious connection between the Amarna Letters and biblical history is that some of the letters appear to be describing, in real-time, the attacks of the Israelites during the period of the conquest. Remember, the initial conquest battles took a period of some 5–6 years17, but the attempts by various tribes to conquer their allotted territories lasted into the period of the Judges.18 The letters from the rulers of some of the very cities named in the biblical conquest calling for help from the attacking ʿapîru/ḫa-bi-ru, provide a poignant backdrop to this period of biblical history.

Milkilu, the ruler of Gezer writes to Pharaoh: “May the king, my lord, be apprised that hostility is strong against me…so may the king, my lord, deliver his land from the hand of the ʿapîru men” (EA271).19 In Joshua 10:33, Horam the king of Gezer is killed in a battle against Joshua’s army, and yet, Joshua 16:10 notes that the Israelites were unable to drive the Canaanites from Gezer, and instead, impressed them into forced labor. Perhaps after the death of Horam, Milkilu was appointed king and found the hostility of the ʿapîru/ḫa-bi-ru to be of such concern that he wrote to Pharaoh for help. Moreover, Waterhouse notes, “A further Gezer missive makes the telling admission that: ‘the Habiru are stronger than we’ (EA299:18–19)…the Israelites were militarily stronger than their foes and were thus able to impress a tribute of servile work upon the Canaanites of Gezer (Josh 16:10). Perhaps this is why Gezer’s ruler reports that people (=his citizens) can be ransomed ‘from the mountains for 30 shekels of silver’ (EA292:48–50). The only way the king of Gezer could rescue those from his own citizenry, who had been made liable to forced labor, was to pay as ransom the going price for a slave.”20

Abdi-Ḫeba, the king of Jerusalem, writes to Pharaoh begging for Egyptian soldiers to be sent to him and warning of the dire situation in Canaan: “May the king turn his attention to the regular troops so that the regular troops of the king, my lord, may come forth. The king has no lands! The ʿapîru men [lit. the ḫa-bi-ru] have plundered all the lands of the king. If there are regular troops in this year, there will still be lands of the king, my lord. But if there are no regular troops, the lands of the king, my lord, are lost” (EA286).21 Joshua 10:1–26 describes a battle Joshua’s army fought against Adoni-zedek, king of Jerusalem, and his coalition of kings from Hebron, Jarmuth, Lachish, and Eglon. Joshua captured them and put them to death. It is interesting that, in EA 286, lines 9–15, Abdi-Ḫeba notes that he was not king by lineage, but was rather appointed by Pharaoh as king. Furthermore, in AE288 (lines 7-15) Abdi-Ḫeba notes that he was just a soldier whom Pharaoh appointed ruler. This seems to imply some exceptional circumstances surrounding his accesssion. It may be that, upon the untimely death of Adoni-zedek, Abdi-Ḫeba was hastily installed as the new king.

Biridiya, the ruler of Megiddo, writes, “I am guarding the city of Megiddo, the city of the king, day and night…But now the hostility of the ʿapîru men is intense in the land so may the king, my lord be apprised concerning his land” (EA243).22 According to the biblical text, the king of Megiddo was killed during a conquest battle (Josh. 12:21), but the Israelites were unable to drive out the inhabitants of Megiddo (Jdg. 1:27). It is quite possible that Biridiya’s defense of the city prevented the Israelites from taking Megiddo, as the Bible describes.

Abdi-Shullim, the ruler of Hazor, writes to Pharaoh stating that he is guarding the city and her towns against “what is being done against the city of Ḥaṣôra (Hazor)” (EA228).23 According to the biblical text, the Israelites defeated Jabin, king of Hazor, and burned parts of the city with fire (Josh. 11:1–13). Yet both the Amarna Letters (EA227 and EA228) and the Bible (Jdg 4:2–3) reveal that Hazor survived and became a city of some influence in Canaan again.

Finally, there is an interesting link between the ʿapîru/ḫa-bi-ru and the city of Shechem. In the book of Joshua, after decisive military victories at Jericho and Ai, the Israelites come to Shechem without any battles to renew their covenant (Josh 8:30–35), suggesting some sort of arrangement between the local leader and the Hebrews. The Amarna letters appear to shed light on this situation, as Lab’ayu, the ruler of Shechem, is accused by Abdi-Ḫeba, the leader in Jerusalem of having “given the territory of Shechem to the ʿapîru men” (EA 289).24 Bryant Wood suggests the fact that Jacob’s descendants retained rights to land at Shechem [Gn 33:19; 48:22; Josh. 24:32] may have resulted in longstanding ties between the Israelites and the people of Shechem.25 The historical tie between the people of Shechem and the people of Israel would plausibly explain some sort of arrangement between them during the conquest period, which would make sense of the close connections seen in the both the Amarna texts and the Bible between the ʿapîru/ḫa-bi-ru (Israelites) and the people of Shechem.

Conclusion

The Amarna Letters describe the situation in Canaan around the time of the biblical conquest. However, one must understand that the conquest was a prolonged affair, and not the lightning-fast, complete devastation some misunderstand from the biblical text. As Kenneth Kitchen rightly pointed out, “The book of Joshua in reality simply records the Hebrew entry into Canaan, their base camp at Gilgal by the Jordan, their initial raids (without occupation!) against local rulers and subjects in south and north Canaan, followed by localized occupation (a) north from Gilgal as far as Shechem and Tirzah, and (b) south to Hebron/Debir, and very little more. This is not the sweeping, instant conquest-with-occupation that some hasty scholars would foist upon the text of Joshua, without any factual justification.”26 Within this context, the Amarna Letters are describing similar events at the same time as the Bible. Simply put, the Canaan of the Bible and the Canaan of the Amarna Letters is one and the same.

At numerous points, the Amarna Letters and the Biblical text align in their description of the geopolitical events in Canaan in the 14th century BC. Some of the references to the ʿapîru/ḫa-bi-ru, who were attacking specific cities named in the conquest narratives, specifically those from the Central Highlands, likely refer to the Israelites. As such, some of the tablets from the el-Amarna archive are relevant letters from the biblical world.

Cover Photo: Amarna Tablets / © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence

Endnotes

1 Charles Aling, “Eighteenth Dynasty Chronology.” Artifax, Summer 2014, 14–16.

2 Ian Shaw, Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 484–485.

3 There is a wider range between the high and low chronologies for earlier pharaohs of the 18th Dynasty. For example, Aling believes Thutmose III reigned from 1504–1450 BC, while Shaw says he reigned from 1479–1425 BC (see above footnotes). However, the chronological gap narrows later in the 18th Dynasty.

4 Anson F. Rainey, ed. The El-Amarna Correspondence. (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 5.

5 Anson F. Rainey, ed. The El-Amarna Correspondence. (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 3.

6 William L. Moran, The Amarna Letters. (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1992), XXVI.

7 Anson F. Rainey, ed. The El-Amarna Correspondence. (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 28.

8 I plan to write a series of blogs based on my Masters thesis that explain the textual variant in the Septuagint (LXX). In it, 1 Kings 6:1 says it was in the 440th year after the Israelites came out of Egypt that Solomon began building the temple in the fourth year of his reign. This is different than the Masoretic Text (MT) which reads “480th” year. If the LXX is the correct reading, the exodus occurred around 1406 BC and the conquest around 1366 BC. This fits with the evidence in the Amarna Letters (if some of the Habiru are indeed the Hebrews); It would be a chronological stretch to associate the Amarna Letters with the conquest if it occurred in 1406 BC (according to the MT).

9 Bryant G. Wood, “The Role of Shechem in the Conquest of Canaan.” Associates for Biblical Research. April 5, 2008. https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/conquest-of-canaan/2608-the-role-of-shechem-in-the-conquest-of-canaan (Accessed Oct. 8, 2021).

10 EA 286, line 56; EA 288, line38.

11 Steven Collins and Joseph Holden, The Harvest Handbook of Bible Lands. (Eugene: Harvest House Publishers, 2019), 126.

12 “Bands of Brigands” is a description for the Habiru that archaeologist Gary Byers prefers. Personal communication. Nov. 8, 2021.

13 S. Douglas Waterhouse, “Who are the Habiru of the Amarna Letters?” Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 12/1 (2001), 31.

14 S. Douglas Waterhouse, “Who are the Habiru of the Amarna Letters?” Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 12/1 (2001), 35.

15 Waterhouse, 35.

16 Anson F. Rainey, ed. The El-Amarna Correspondence. (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 699.

17 In Joshua 14:7-10, Caleb asks for his inheritance in the land, noting that he was 40 years old when he spied out the land, and that his request was coming 45 years later. Taking into account the 40 years of wandering in the wilderness, this would mean the conquest had been on-going for five years by this point.

18 See the first chapter of the Book of Judges.

19 Anson F. Rainey, ed. The El-Amarna Correspondence. (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 1071.

20 S. Douglas Waterhouse, “Who are the Habiru of the Amarna Letters?” Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 12/1 (2001), 36.

21 Anson F. Rainey, ed. The El-Amarna Correspondence. (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 1108–1109.

22 Rainey, 999.

23 Rainey, 967.

24 Rainey, 1121.

25 Bryant G. Wood, “The Role of Shechem in the Conquest of Canaan.” Associates for Biblical Research. April 5, 2008. https://biblearchaeology.org/research/chronological-categories/conquest-of-canaan/2608-the-role-of-shechem-in-the-conquest-of-canaan (Accessed Oct. 8, 2021).

26 K. A. Kitchen, On The Reliability of the Old Testament. (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2006), 163.

4 – t

Thanks Bryan. Always top notch work. Regarding footnote 8 and the geo-political situation in Canaan…while various tribes continued to conquer their allotted territories into the period of the Judges, IMO, from a chronological perspective, you need not grant that the Amarna letters refer to the period during the mid-1300’s (longer than needed after the initial conquest battles). Sorry if I may seem like a broken record, but I recommend the arguments set forth by the late Christine Tetley be seriously considered. These can be found in “The Reconstructed Chronology of the Egyptian Kings” (pdf available for free online) as well as her first book on “The Reconstructed Chronology of the Divided Kingdom.” Although I would differ with Tetley in many respects, her anchor dates (especially for Amenhotep I in 1651 BC) can be used to place Amenhotep II (the Pharoah of the Exodus in 1547 BC) just beginning to reign in 1548. This relates to the pharaohs of the Amarna letters as follows: Amenhotep III (1514-1476) the pharaoh during the conquest, and then Akhenaten (1476-1459) reigned during the 5th year of oppression by Cushan-Rishathaim near the beginning of the Judges period. If these drastically different dates (~100 years earlier than what is currently accepted) seem ridiculous, please be advised that the LXX-L chronology coincides much better with these earlier dates (with the divided kingdom in 986 BC and the 440 years as cumulative & autonomous, not consecutive, years). Maybe someday Tetley will get the credit she deserves (and don’t forget yours truly ;>)