NOTE: My research has been published as a book by Trowel Press entitled Joshua’s Jericho: The Latest Archaeological Evidence for the Conquest. It is available through Amazon here: https://a.co/d/iCUWXQW

In Part 1, I outlined my view that Jericho City V, not City IV is Joshua’s Jericho. I did not come to this conclusion lightly, but rather after hundreds of hours of study, two trips to Tell es-Sultan/Jericho, analyzing the latest research from the most recent excavations, and reading the older reports from the previous digs.

In Part 2, I will share my unique approach to the dating of the conquest. This is important because, if you look in the wrong general time period, you will miss the potential evidence for the conquest.

The more I have studied the relevant biblical texts, the more I have become uncomfortable confidently asserting specific year1 (or day!2) for the exodus/conquest. I still believe the biblical data leads to an early date for the exodus/conquest, not a late date3; however, I see too much imprecision in the chronological information presented in the Bible to identify precise, absolute dates for these events.

Holding to a specific year becomes problematic since it forces one to fit the archaeological data that might support the exodus and conquest within a rigidly narrow timeframe for these events. My approach involves analyzing the data in the biblical text and then, based upon this and other factors, developing a chronological window within which the exodus/conquest occurred. Since archaeological evidence can rarely be dated to a single year, this approach provides greater flexibility when analyzing the potential supporting evidence.

The Key Text

The Bible verse that provides the most specific chronological data with which to date the exodus/conquest is 1 Kings 6:1, which reads, “In the four hundred and eightieth year after the people of Israel came out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel, in the month of Ziv, which is the second month, he began to build the house of the LORD” (ESV). Many scholars point to 967 BC4 as the fourth year of Solomon’s reign, which means one merely counts back 479 years to arrive at 1446 BC for the date of the exodus. The conquest began after wandering for 40 years in the wilderness, or in 1406 BC.

Imprecision Surrounding the Key Text

However, in the Septuagint, 1 Kings 6:1 says that it was in the 440th year, not the 480th year. The Septuagint (LXX) is a stream of Greek translation which predates the Masoretic text by hundreds of years. Moreover, the LXX is translated from a Hebrew source, possibly an Hebrew manuscript of the Old Testament from Egypt.5 In fact, numerous Hebrew manuscripts were discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls that appear to be the sources for the LXX. DSS expert, Peter Flint, notes numerous manuscripts which align more closely with the LXX than the MT.6 While many believe the MT is more reliable than the LXX, one should not dismiss the latter so quickly. Jesus quoted from the LXX7 and it is the main source for quotations by the New Testament writers.8 In other words, Jesus and the apostles read and quoted from a translation of the Bible that almost certainly read “In the 440th year….” (1 Kgs 6:1).

In his well well-researched study of the textual variant in 1 Kings 6:1, Henry Smith Jr. concluded that “440th” is likely the original Greek translation, and while he sides with the 480th reading of the MT (for external reasons), he admits it is “by no means a text critical slam dunk.”9

If the LXX reading of “440th year” is the authentic reading, then the exodus occurred in 1406 BC and the conquest in 1366 BC. So, while both texts give a precise number, there is uncertainty surrounding which is the correct date.

Moreover, there is imprecision surrounding the anchor date of the fourth year of Solomon’s reign. While Rodger Young identifies 967 BC as the fourth year of Solomon’s reign (see footnote 3), Edwin Thiele placed this in 966 BC.10 According to William F. Albright’s dating, the fourth year of Solomon’s reign was in 959 BC,11 while Kathleen Kenyon believed it was in 960 BC.12 In other words, the very anchor date for establishing the exodus/conquest is debated, leading to a window of almost a decade. I believe one can state that Solomon began building the temple sometime between 959 BC and 967 BC. However, confidently stating a specific year, in my opinion, likely rests upon overstating one’s case.

Imprecision in Archaeological Dating Methods

Some people mistakenly think that archaeology can be used to date events to a specific year. The reality is that there is that most produce a window of time in which an event occurred. In other words, there is a level of imprecision in the archaeological dating methods themselves.

First, there is imprecision surrounding the chronology of the Late Bronze (LB) Age and the Egyptian chronology of the 18th Dynasty, upon which the different phases of the Late Bronze Age are based. The LB I is divided into LB I

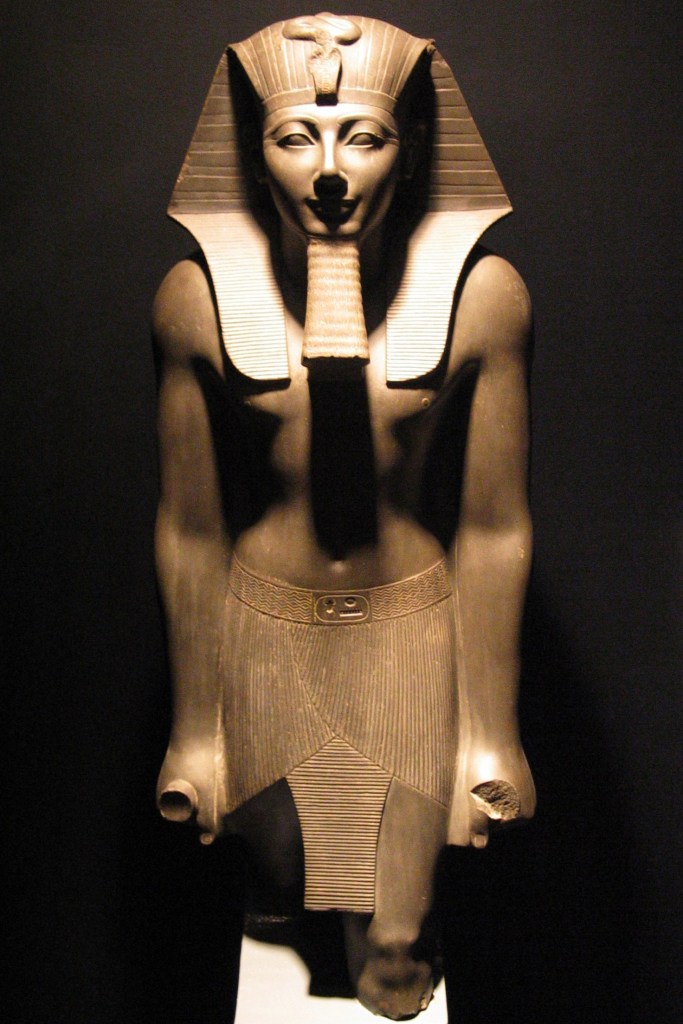

First, there is some uncertainty regarding the chronology of the Late Bronze (LB) Age and its correlation with the Egyptian chronology of the 18th Dynasty, on which the various phases of the Late Bronze Age are based. The LB I period is divided into LB IA and LB IB (15th century BC) primarily based upon whether a certain archaeological level comes before or after Thutmose III’s campaign into Canaan.13 However, Egyptologists cannot even agree when Thutmose III reigned. Those who hold to the high chronology say he reigned around 1504 BC to 1450 BC14, while those who hold to a low chronology believe he reigned around 1479 BC to 1425 BC.15 Kenneth Kitchen notes that there is a margin of error of up to 20 years for the Pharaohs of the 18th Dynasty.16

Secondly, the primary dating method used by archaeologists is ceramic typology. The LB I period is usually dated from 1550 BC to 1400 BC and the LB II period from 1400 BC to 1200 BC. However, it is not like potters woke up on January 1, 1400 BC and decided to scrap their old pottery forms and make entirely new ones. Some vessels changed little over the centuries, and were often used from one period to the next.17 In my personal communication with Dr. Robert Mullins, the world’s leading LB ceramicist, he has used the phrase “LB IB/II A horizon” to discuss Canaanite pottery of this period.18

Thirdly, archaeologists use radiocarbon dating when possible. However, the results are given as a date range, usually decades in length, not a specific year. Moreover, the calibration curve is continually being updated.

My Chronological Window Approach

Because the Bible’s timeline isn’t exact and archaeological dating can only give a range of possible years, it’s more realistic to think in terms of a chronological window for the exodus and conquest, rather than trying to pinpoint the exact year. As we’ve seen, there is a known margin of error of decades in each of the three archaeological dating methods mentioned.

With this in mind, I’ve chosen to use a window of ±20 years around the two main possible biblical dates for these events. If the Hebrew text (MT) is correct, the conquest of Canaan would have begun around 1406 BC. If the Greek version (LXX) is right, the conquest would be dated to around 1366 BC. With my ±20-year window around each of these dates, the archaeological timeframe for the fall of Jericho would be between 1426 and 1346 BC.

In part three, we’ll begin to look at the archaeological evidence for occupation during this chronological window.

Cover Photo: Bill Schlegel / BiblePlaces.com / Used with Permission

Endnotes:

1 The commonly cited early date for the exodus is 1446 BC, with the conquest occurring 40 years later in 1406 BC. See Bryant Wood’s article, “The Rise and Fall of the 13th Century Exodus-Conquest Theory.” Online: https://biblearchaeology.org/research/contemporary-issues/2579-the-rise-and-fall-of-the-13th-century-exodusconquest-theory (Accessed Oct. 24, 2025).

2 Douglas Petrovich, “Amenhotep II and the Historicity of the Exodus Pharaoh.” The Masters Seminary Journal. 17.1 (Spring 2006): 4, footnote 22.

3 For a good overview of why the early date (15th/14th century BC) and not the late date (13th century BC) is correct, I recommend Dr. Scott Stripling’s two-part interview on Digging for Truth: https://youtu.be/bxXXTGD_y40?si=KoF8mB7Oz_ZG0ljO and https://youtu.be/8-mUoS5RvBU?si=ksHpFuUCE7NiTiUg (Accessed Oct. 29, 2025).

4 For example, see Roger C. Young, “When Did Solomon Die?” JETS 46/4 (December 2003): 602.

5 Donald J. Wiseman, Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries: 1 and 2 Kings. (Nottingham: InterVarsity Press, 1993), 63.

6 Peter Flint, The Dead Sea Scrolls. (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2013), 86–104.

7 Craig A. Evans, “The Scriptures of Jesus and His Earliest Followers.” In The Canon Debate, edited by Lee Martin McDonald and James A. Sanders. (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, Inc, 2002), 192.

8 Natalio Fernandez Marcos, The Septuagint in Context: Introduction to the Greek Version of the Bible. (Boston, Brill, 2000), 324.

9 Henry Smith Jr, Henry, “1 Kings 6:1 and the Date of the Exodus from the Masoretic and Septuagint Textual Traditions,” NEASB 69 (2024): 52.

10 Edwin R. Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1983), 80.

11 W.F. Albright, “The Chronology of the Divided Monarchy of Israel Author.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 100 (Dec. 1945): 20.

12 Kathleen M. Kenyon, Digging Up Jericho. (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1957), 259.

13 Robert A. Mullins and Eli Yannai, “Late Bronze Age I–II,” in The Ancient Pottery of Israel and its Neighbours, Volume 3: from the Middle Bronze Age through the Late Bronze Age, ed. Seymour Gitin. (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2019), 151.

14 Charles F. Aling, “Eighteenth Dynasty Chronology.” Artifax, Summer 2014: 15.

15 Ian Shaw, ed., Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 485.

16 K.A. Kitchen, “The Chronology of Ancient Egypt.” World Archaeology, 23-2 (1991), 204.

17 Robert A. Mullins and Eli Yannai, “Late Bronze Age I–II,” in The Ancient Pottery of Israel and its Neighbours, Volume 3: from the Middle Bronze Age through the Late Bronze Age, ed. Seymour Gitin. (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2019), 151.

18 Robert Mullins, Email message to the author, Nov. 6, 2024.

Thanks for engaging with these latest chronological and archeological questions!

I especially appreciate your (more open minded) chronological “window” approach. I hope you won’t mind, I’d like to offer a few differing interpretations to perhaps foster consideration of an even larger perspective.

For example, regarding 1Kings 6:1, rather than taking the 480 years as consecutive years, I suggest using the Septuagint’s “440th year” (439 years), yet understanding that number as a cumulative calculation of Israel’s “righteous” years (as a convenient & succinct way of putting it). That is, I have found that, utilizing the numbers of the LXX-OG text, when periods of oppression and God’s judgment are excluded, 439 years can reasonably be summed up between the Exodus and the foundation of the temple. This proposal is similar to suggestions by scholars like Lightfoot, Nöldeke/G.F. Moore and others. It is not unheard of since it actually aligns with examples of ancient chronological customs (such as found in Egyptian records) that don’t always count years of foreign domination or usurpers.

This approach allows for some overlapping of the Judges periods (similar to Steve Rudd). It also aligns with Jephthah’s 300 years and the overlap of the 490 years of unkept Sabbath cycles.

Also, regarding the Temple anchor date, I’m glad you acknowledge the variation among chronologists (Young 967 BC, Thiele 966 BC, Albright 959 BC, Kenyon 960 BC). Based on the seminal work of Christine Tetley utilizing the LXX-L text (“The Reconstructed Chronology of the Divided Kingdom”) coupled with my opinion (also expressed by others), that Solomon waited 11 months from the completion of the temple until the Jubilee year for its dedication, I would place the dedication of the temple in 1015 BC, which is one jubilee cycle earlier than others (who hold to the Thiele chronological school). Thus, I would place Solomon’s 4th year as 1022 BC with a 525-year total time interval from the Exodus. My early date for the temple aligns with an unabbreviated perspective on the period of the divided monarchy that is very close to Christine Tetley’s reconstruction of the divided kingdom (DK). She begins the DK in 981 BC, but I date the division to 986 BC. (The Thiele school places the DK in 931/930 BC.) In my opinion, an LXX based chronology has the great advantage of taking the Biblical text seriously rather than forcing the biblical chronology to conform to the Assyrian Eponym Canon through coregencies unattested by the text (as the Thiele school does).

Conventional date advocates may find some comfort in that, according to Stephen C. Meyers (“The Date of the Exodus According to Ancient Writers”) a consensus of ancient writers (five of the six writers cited by Meyers, who dated the temple) held to a ~960 BC temple date. While I do not find myself agreeing with the ancients in that regard, I do agree with their general opinions regarding the date the Exodus. I date the Exodus to 1547 BC. So, it is interesting (and perhaps telling) that 14 of 18 ancient writers cited by Meyers differ from modern conservative opinion in that they mostly place the Exodus in the mid-16th century BC (~1550 BC +/- 20 years) rather than the mid-15th century. These ancient sources also understood the time interval from the Exodus to the temple foundation as 565-595 years on average (not simply 479/480 consecutive years).

These alternative interpretations support dates that align more readily with radiocarbon dating – and thus, IMO, argue in favor of the archaeology of Jericho City IV, rather than City V.

I look forward to Part 3!