In this five-part series, I will present a general overview of the latest research on Jericho in the Late Bronze Age. This was the subject of my Master’s thesis and was recently published as a book entitled Joshua’s Jericho: The Latest Archaeological Evidence for the Conquest, from Trowel Press. It is available from Amazon here: https://a.co/d/iCUWXQW

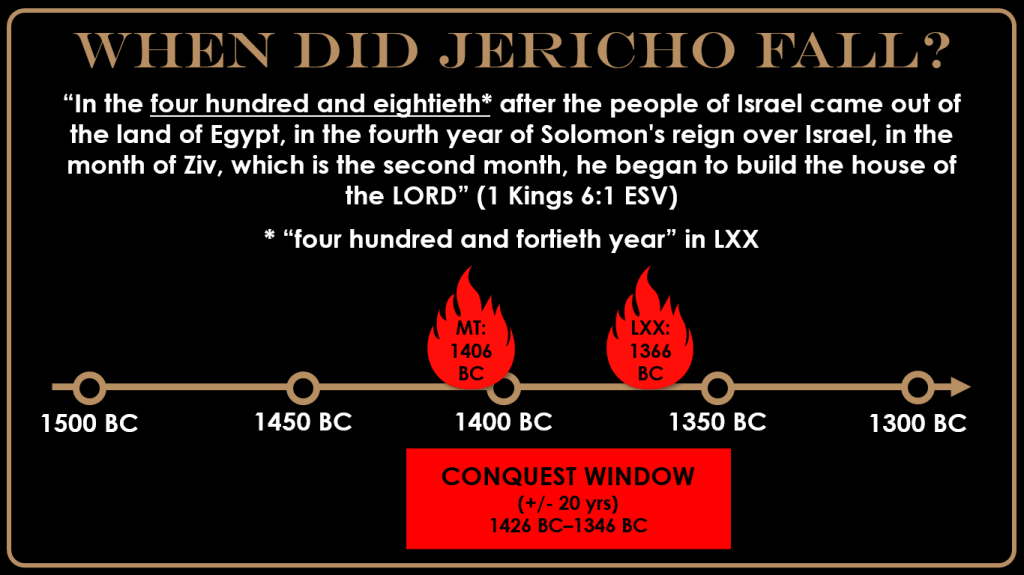

In Part One, I set the stage by reviewing the major excavations that have taken place at Jericho and accepted the most recent stratigraphy of the team from Sapienza University that City V, not City IV was the Late Bronze (LB) city. In Part Two, I presented my unique approach to dating the exodus and conquest by noting the imprecision surrounding the biblical chronological data and the margins of error in archaeological dating methods. I use a window of ±20 years around the two main possible biblical dates for these events (1406 BC if the Masoretic text of 1 Kings 6:1 is correct and 1366 BC if the Septuagint reading is correct), resulting in an archaeological timeframe for the fall of Jericho between 1426 and 1346 BC. In Part Three, we will analyze three lines of archaeological evidence that demonstrate Jericho was occupied within this chronological window.

Pottery

LB pottery was discovered at Jericho by every major excavation team. Sherds and vessels were discovered all around the tell, but primarily on Spring Hill, the outcrop on the eastern side of the tell overlooking the spring where a series of palaces once stood. Most of the pottery comes from Garstang’s Middle Building, which Nigro calls “the Residency.”1 Dating the pottery from this building is difficult, which resulted in a famous debate in the pages of BAR in the 1990s by Bienkowski and Wood.2 Garstang, who originally excavated the Middle Building, came to believe the painted pottery from this area dated to the LB IIA period (ca. 1400–1300 BC).3 Robert Mullins, the leading expert on LB pottery, has noted, “Based on the available pottery (in publication as well as what can be seen physically from Jericho) City V is LB IIA.”4 Having studied Garstang’s pottery sherds in-person at the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem, and having compared these to similar pottery assemblages at six other sites within 50 miles of Jericho,5 I would date the pottery sherds to the LB IIA period as well.

In addition to the pottery from the Middle Building, Kenyon also excavated a domestic structure, which she dated to the 14th century.6 She discovered a mendable dipper juglet lying on the floor of this house beside an oven. She wrote, “The evidence seems to me to be that the small fragment of a building which we have found is part of the kitchen of a Canaanite woman, who may have dropped the juglet beside the oven and fled at the sound of the trumpets of Joshua’s men.”7

Garstang also excavated three tombs8 that had been used in the LBA, and discovered over 200 pieces of LB pottery within, including many whole vessels. He dated these to the LB I period.9 However, Kenyon believed most of these vessels dated to the LB IIA period, writing that the tombs “were reused between about 1400 BC and c. 1350–1325 B.C.”10 According to Nigro, Tomb 5 contained vessels datable as early as 1450–1400 BC, while Tombs 4 and 13 yielded vessels datable to 1375–1275 BC.11

The takeaway from all of this is that the pottery indicates Jericho City V was occupied within the chronological window set for the fall of Jericho.

Scarabs

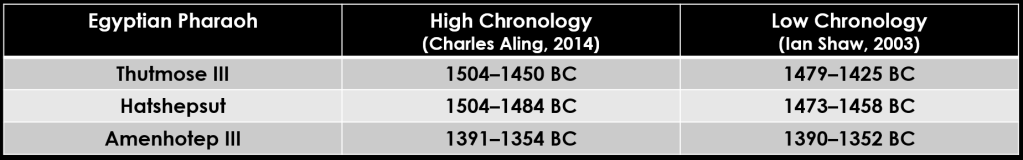

John Garstang also discovered a seal of Thutmose III and a scarab of Hatshepsut in Tomb 5 and two scarabs of Amenhotep III in Tomb 4. All three of these scarabs were found within the LB levels of the tombs.12 Pharaohs like Thutmose III and Amenhotep III were popular and revered long after their deaths. Consequently, their scarabs were copied and collected for many years and are therefore not always helpful in determining an occupational date. However, if they are found in a layer dating to the reign of said pharaoh, then they can be used to date a site. This was the case with the scarabs of Amenhotep III, which were discovered while sifting material from a level that included LB IIA vessels.13 Given that Amenhotep III reigned in the LB IIA period, and his scarabs came from an LB IIA context, the scarab can be used to date the occupation of Jericho to the LB IIA period. Hatshepsut’s scarab is also helpful for dating. Unlike popular pharaohs like Thutmose III and Amenhotep III, Hatshepsut was despised, and her name was systematically erased from inscriptions in Egypt in antiquity.14 Her scarabs are rare because they were not copied or kept as amulets. This makes the Hatshepsut scarab a good chronological indicator,15 implying some occupational evidence in the LB IB period. Regardless of whether one uses the high16 or low17 Egyptian chronology, the series of scarabs indicates occupation at Jericho City V during the late 15th and early 14th centuries BC, within my chronological window for the conquest.

Cuneiform Tablet

Garstang also discovered a cuneiform tablet on the eastern slope of the tell, just outside the Middle Building. He described it as “most similar to the Tell el-Amarna tablets” and estimated that it most likely dated to the 14th century BC.18 The tablet discovered by Garstang was significantly damaged, and only a handful of signs are discernible, not enough to translate anything meaningful with certainty. One partial translation reads, “…older? S[o]n of Ta[g]atuka…”19 Even though the inscription cannot be meaningfully read, there are potentially important inferences that can be drawn from its discovery, especially if it dates to the Amarna period. Nigro summarized the importance of this discovery as it relates to City V: “On the eastern flank of the tell, Garstang retrieved a LB clay tablet preserving an administrative text, which suggests that the city still had a political role, a palace, a ruler, and even an archive”20

Conclusion

The dates of the pottery discovered on the tell and in the tombs, along with the scarabs and the cuneiform tablet, all fit within the chronological window I established for the conquest. The archaeological evidence clearly indicates that Jericho City V was occupied at the time the Bible indicates the fall of Jericho occurred.

Is there evidence that Jericho was fortified and destroyed within the chronological window? Stay tuned for my next blogs.

Cover Photo: Bill Schlegel / BiblePlaces.com / Used with Permission

Endnotes

1 Lorenzo Nigro, “Tell es-Sultan/Jericho in the Late Bronze Age,” in Durch di Zeiten: Through the Ages, eds. Katja Soennecken, Patrick Leiverkus, Jennifer Zimni and Katharina Schmidt. (Munich: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 2023), 605.

2 Bienkowski argued that the painted pottery discovered by Garstang on the tell was not LB I Cypriot bichrome ware, but rather it was standard LB II painted ware that came from the rooms of the Middle Building, referring to the room numbers written on the pottery sherds. Wood responded that the fabric of the sherds was finer and of better quality than the relatively poor LB II pottery, and must therefore date to the LB I, and that this pottery came from the erosional layers above or beneath the Middle Building, even though it was labelled with the room numbers of the Middle Building. See Piotr Bienkoswki, “Jericho Was Destroyed in the Middle Bronze Age, Not the Late Bronze Age.” Biblical Archaeology Review 16.5 (September/October 1990), 45–46 and Bryant G. Wood, “Dating Jericho’s Destruction: Bienkowski Is Wrong on All Counts.” Biblical Archaeology Review 16.5 (September/October 1990), 45–68.

3 John Garstang and J.E.B. Garstang. The Story of Jericho. (London: Marshall, Morgan & Scott, Ltd., 1948), 177–180.

4 Robert Mullins, Personal Communication, 2024.

5 Tall el-Hammam, Shiloh, Shechem, Tel Batash, Beth Shean, and Tel Esur

6 Kathleen M. Kenyon and Thomas A. Holland, Excavations at Jericho, Vol. Three. (London: British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, 1981), 371 and Kathleen M. Kenyon, Digging Up Jericho. (ew York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc., 1957), 261, 263.

7 Kathleen M. Kenyon, Digging Up Jericho. (ew York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc., 1957), 263.

8 Tombs 4, 5, and 13.

9 Garstang, John, “Jericho: City and Necropolis.” University of Liverpool Annals of Archaeology

and Anthropology, Vol. XX, 1933, 19-36.

10 Kathleen M. Kenyon, Digging Up Jericho. (ew York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc., 1957), 261.

11 Lorenzo Nigro, “Tell es-Sultan/Jericho in the Late Bronze Age,” in Durch di Zeiten: Through the Ages, eds. Katja Soennecken, Patrick Leiverkus, Jennifer Zimni and Katharina Schmidt. (Munich: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 2023), 607.

12 Garstang, John, “Jericho: City and Necropolis.” University of Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology, Vol. XX, 1933, 22, 27.

13 Garstang, John, “Jericho: City and Necropolis.” University of Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology, Vol. XX, 1933, 27.

14 Joyce Tyldesley, Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh. (London: Viking, 1996), 114–115.

15 Bryant G. Wood, “Dating Jericho’s Destruction: Bienkowski Is Wrong on All Counts.” Biblical Archaeology Review 16.5 (September/October, 1990), 49.

16 Charles F. Aling, “Eighteenth Dynasty Chronology.” Artifax, Summer 2014, 15–16.

17 Ian Shaw, ed. Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 485.

18 Garstang, John. 1934. “Jericho: City and Necropolis, Fourth Report.” University of Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology, Vol. XXI, 116, 117.

19 W. Horowitz and T. Oshima, Cuneiform in Canaan, Cuneiform Sources from the Land of Israel in Ancient Times (Jerusalem, Israel Exploration Society, 2006), 96.

20 Nigro, Lorenzo. 2016b. “TELL ES-SULTAN 2015: A Pilot Project for Archaeology in Palestine.” Near Eastern Archaeology 79.1 (2016), 16.