Here is the video version of this blog:

Every year, when my calendar flips to December, I know I will start to see the Pagan Christmas memes showing up in my social media feeds. These typically all make the same claim that various elements of Christmas are copied from pagan religions.

Depending on how one defines the word pagan, I would not have a problem with taking something that was pagan and redeeming it for good. Within the context of Christianity, the Miriam-Webster dictionary defines pagan as non-religious or non-Christian.1 By this definition, an electric guitar is a pagan instrument, having been developed in the 1930s and 1940s for non-Christian purposes by pioneers such as George Beauchamp, Adolph Rickenbacker, and Les Paul.2 Yet I regularly play the electric guitar as part of our worship team. My “pagan” electric guitar is being used for God-honoring purposes.

However, having looked into the source material of these claims, I’ve discovered that the claims made by most of these memes are false. When it comes to Christmas, Christians didn’t steal the ideas from the pagans. In fact, some scholars believe it was the other way around – that the pagans chose to copy Christian practices.

Here then are three of the most common myths about the pagan roots of Christmas.

Myth #1 – The Date of Christmas

This urban myth goes something like this: Christians chose Dec. 25th as the date of Christ’s birth to counter a pagan feast, sometimes identified as Sol Invictus or Saturnalia. The problem with this claim is that the historical evidence and timeline does not back it up.

Unlike Christ’s resurrection, which has been celebrated almost continuously since Jesus rose from the dead, celebrations of the birth of Christ came later in history. Still, by the end of the second century, Christians were trying to determine when Jesus was born, with several dates being suggested. In the third and fourth centuries, December 25th was one of the dates Christians had settled on. Only later did the Sol Invictus feast possibly become associated with the date; Saturnalia was never celebrated on December 25th.

Here is the timeline:

Photo: Firenze. Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana. Used with Permission

195 AD – Clement of Alexandria writes, “And there are those who have determined not only the year of our Lord’s birth, but also the day; and they say that it took place in the twenty-eighth year of Augustus, and in the twenty-fifth day of Pachon [May 20]…others say that He was born on the twenty-fourth or twenty-fifth of Pharmuthi [April 19 or 20].”3

211 AD – Hyppolitus of Rome writes in his commentary on Daniel that Jesus was born eight days before the Kalends of January (ie, December 25th).4

221 AD – Julius Africanus writes his Chronographiai, in which he calculates that Jesus was born in 42 Augustus (or around 2 BC).5

336 AD – Within the Philocalian Calendar, there is an earlier section dating to 336 AD, called the Depositio martyrum (“list of martyrs’ feasts”), which includes an entry, “VIII kal. Ian. natus Christus in Betleem Iudaeae” (“Eighth day before the Kalends of January, the birth of Christ in Bethlehem of Judea”). This places a feast celebrating Christ’s birth on December 25th.6

354 AD – The Philocalian Calendar of 354 AD (Part VI) has an entry for December 25th that reads: “N · INVICTI · CM · XXX” (“Natalis Invicti, games ordered, thirty [chariot] races.”7 It’s important to note that this does not say Sol Invictus, simply Invictus, but is generally assumed to be referring to this festival. If so, this is the earliest reference to Sol Invictus being celebrated on Dec. 25th. However, before 354 AD, Sol Invictus was celebrated on other days. Imperial fasti (ancient Roman calendars that recorded religious festivals and official events) note that Sol Invictus was celebrated on August 8, August 9, August 28, and December 11.8 Moreover, the Philocalian Calendar itself notes October 19 as “LVDI·SOLIS” (Games of the Sun) and Oct. 22 as “SOLIS·CM·XXXVI” (Sun, circenses missus “games ordered,” i.e. 36 chariot races).9 Indeed, there is evidence that, in AD 274, Aurelian instituted games in honor of Sol, which were held from Oct. 19-22.10

All of this leads me to the following conclusions:

a. The contention that Sol Invictus was held on December 25th is tentative at best, and if it was, it was added to other, earlier dates on which these celebrations were traditionally held, the most important of which was October 19–22.

b. Over a century before Sol Invictus was supposedly celebrated on Dec. 25th, Christians in North Africa were trying to pinpoint the day of Christ’s birth.

c. The first evidence we have of Sol Invictus possibly being celebrated on December 25th is in 354 AD, decades after Christians were already celebrating a feast in honor of Christ’s birth on December 25th.

If anything, it could be argued the Romans changed their feast day to compete with the Christians’ celebration, not the other way around.

Indeed, Wes Huff notes, “In reality, Roman temple worship was on the decline by the fourth century. It is just as possible, and even more probable, that the pagans moved their celebrations to Dec. 25th to compete with the Christians, who were a growing religious majority at the time.”11

Others suggest Saturnalia was celebrated on December 25th, but this is not the case. Macrobius, writing around 431 AD, provides the date for Saturnalia, the feast honoring the Roman god of seed and sowing. He writes, “Among our ancestors the Saturnalia was confined to one day, the fourteenth before the Kalends of January, but after Gaius Caesar gave the month two more days, it began to be celebrated on the sixteenth day before the Kalends.”12 In Roman dating, “the fourteenth before the Kalends of January” means 14 days before January 1, or December the 19th. When Julius Caesar reformed the Roman Calendar, this feast was moved two days earlier (Dec. 17th).13 So it appears Saturnalia was not associated with December 25th.

Then why December 25th, we don’t know for sure, but two plausible suggestions have been made. First, some early Christians believed Jesus was both conceived on and died on March 25,, which would mean he was born on Dec. 25th.14 For example, Thomas C. Schmit has demonstrated that Hippolytus of Rome likely identified December 25th as the date of Christ’s birth because he believed died on March 25th and was also conceived on that day, which he also believed was the anniversary of the creation of the world.15

The other suggestion, is that December 25th, believed to be the winter solstice, was a fitting date for Jesus, who is the true “sun of justice.”16

While we cannot say for certain why Christians chose December 25th to celebrate Christ’s birth, we do know that they were honoring this day decades before the Romans supposedly moved their Sol Invictus celebration to it.

Myth #2 – The Virgin Birth of Other gods

This urban myth suggests that Christians stole the “virgin birth” motif for their God, Jesus, from the virgin birth accounts of other gods, supposedly including Mithra, Horus, and Thammuz, who are said to have also been born on December 25th. So let’s see if there is any evidence to back up these claims.

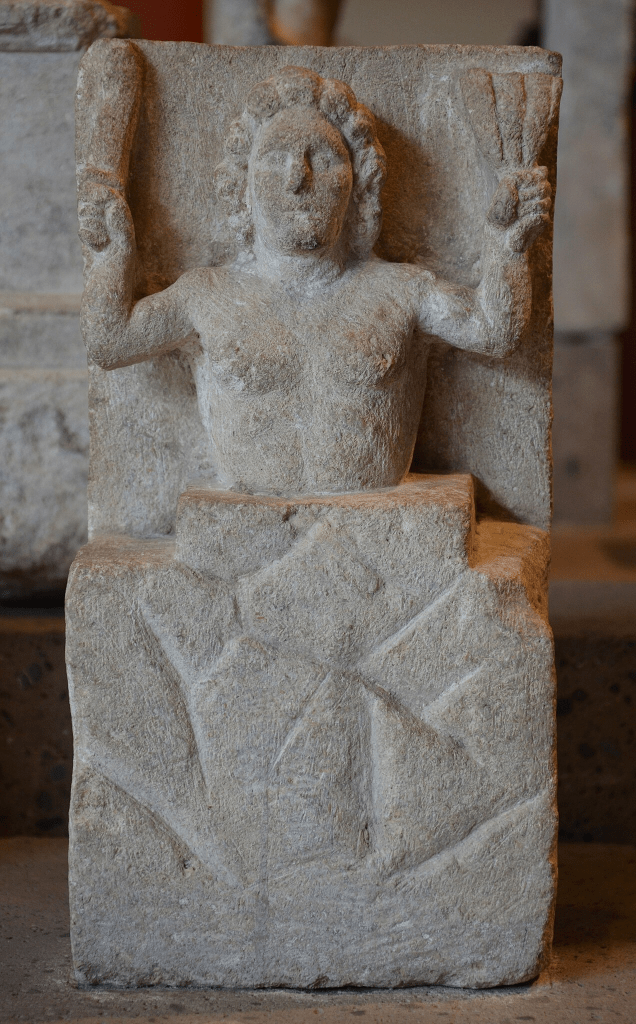

a. Mithra

Carole Raddato / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 2.

There is literally no historical evidence providing the date of Mithra’s birth. However, all of the ancient literary and archaeological evidence is clear, that Mithra was born, fully grown, out of a rock. The ancient poet Commodanius wrote, “Inuictus de petra natus si deus habetur” (The unconquered one, born from a rock, if he is considered a god).167 In his book, The Roman Cult of Mithras, Manfred Claus notes that the literary sources are “unmistakeable: Mithras was known as the rock-born god…The inscriptions confirm this nomenclature: one even reads… ‘To the almighty God Sun invincible, generative god, born from the rock.’ Mithras here is invoked as the all-powerful, invincible sun-god, as creator-god, and as rock-born.”18 Moreover, multiple ancient statues and reliefs depict Mithra emerging from a rock. There is no virgin girl involved in Mithra’s birth accounts.

b. Horus

Similarly, there are no dates associated with the birth of Horus, nor any descriptions of him being born in a cave, with his birth being announced by a star in the east and being attended by wise men. Seriously, there is absolutely nothing; these claims are simply made up for the meme! Moreover, Horus is the son of Osiris and Isis, not born of a virgin. The Pyramid Texts of Pepi I (ca. 2321–2287 BC), Utterance 573 records, “Horus has loved thee, he is thy son, the son of Osiris.”19 In an Egyptian story called, “The Contendings of Horus and Seth,” which dates to the New Kingdom period, it clearly states that Horus was the son of Osiris and Isis.20

c. Tammuz

It is sometimes suggested that Tammuz, also known as Dumuzi, the Mesopotamian fertility god, was born of a virgin on December 25th. However, this is also false. There is no historical evidence associating Tammuz with any dates in December. Rather, the cult of Tummaz was centered around two yearly festivals: one celebrating his marriage to the goddess Inanna in Feb-March, and one in March-April honouring his death.21 Moreover, ancient sources are clear that he was not born of a virgin. He was the son of Enki, one of the most powerful gods in the Mesopotamian pantheon, and the goddess Dutter. The ancient Sumerian poem, The Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi, states that he was “conceived on the sacred marriage throne.”22 So no virgin birth on December 25th here either.

Myth #3 – Christmas Symbols and Traditions

According to this myth, many of the traditions and symbols associated with Christmas have pagan origins.

a. The Christmas Tree

For example, some memes suggest that Christmas trees have roots in pagan worship and are explicitly condemned in the book of Jeremiah. To be sure, ancient people did include trees in their worship. In the late Second Century, Maximus of Tyre recorded that the “worshippers of the oak in Dodona [Greece], who lie on the ground, and whose feet are unbathed, deliver oracles…which they derive from the oak”23 and that the Celts “venerate Jupiter, but the Celtic statue of Jupiter is a lofty oak.”24 However, this is a far cry from decorating a (real or imitation) pine tree with tinsel and lights, which has no religious significance to most. According to the Oxford Handbook of Christmas, “The most certain historical knowledge we have of the tree used in home decoration during Christmas comes from the sixteenth-century German-speaking lands of the Alsace region.”25

Furthermore, those who assert that Christmas trees are explicitly condemned in the book of Jeremiah take the passage out of context. A simple reading of the entire chapter reveals that Jeremiah is condemning the making of literal idol statues from trees. The passage goes on to say, “Their idols are like scarecrows in a cucumber field, and they cannot speak; they have to be carried, for they cannot walk. Do not be afraid of them, for they cannot do evil, neither is it in them to do good” (Jer. 10:5 ESV). So as long as one is not worshiping their Christmas tree as a god and living in fear of it, there is nothing wrong with this tradition.

b. Mistletoe

Kissing under the mistletoe is another Christmas tradition that is said to have roots in Druid worship. It is true that Pliny the Elder describes the Druids of Gaul using mistletoe in their religious rituals:

[Mistletoe] is gathered with rites replete with religious awe…Having made all due preparation for the sacrifice and a banquet beneath the trees, they bring thither two white bulls, the horns of which are bound then for the first time. Clad in a white robe the priest ascends the tree, and cuts the mistletoe with a golden sickle, which is received by others in a white cloak. They then immolate the victims, offering up their prayers that God will render this gift of his propitious to those to whom he has so granted it. It is the belief with them that the mistletoe, taken in drink, will impart fecundity to all animals that are barren, and that it is an antidote for all poisons Such are the religious feelings which we find entertained towards trifling objects among nearly all nations.26

However, the modern tradition of kissing under the mistletoe is not a religious rite. It’s merely a quaint tradition. Moreover, there is no mention that the Druids kissed under the mistletoe. It does not logically follow that because they used the same plant in their religious ceremonies, kissing under the mistletoe has pagan roots. In actual fact, the first historical reference to using mistletoe as a Christmas decoration comes from Robert Herrick’s poem “Ceremonies for Christmas Eve,” published in 1648 in England. In it the opening stanza reads:

Down with the rosemary and bays,

Down with the mistletoe;

Instead of holly, now up-raise

The greener box (for show).27

By the 18th century, elaborate kissing bough/bushes of mistletoe were hung in farmhouses and kitchens throughout England.28 Again, there are no pagan roots to this tradition.

c. St. Nicholas/Santa Claus

Finally, no blog about the supposed pagan roots of Christmas would be complete without addressing Santa Claus. The historical roots of the imaginary jolly man dressed in red go back to a real person named St. Nicholas, the Bishop of Myra (modern-day Demre, Turkey), who lived sometime between 260 and 343. He is famous for giving three bags of gold as dowries for his poor neighbor’s three daughters so they could marry. St. Nicholas died on Dec. 6, 343, and soon a tradition arose of gift-giving on his feast day.29 This tradition spread to other countries, including Holland, where “Sint Nikolaas” became known as “Sinterklaas.” In the 17th century, Dutch settlers brought their Sinterklaas traditions to America, where the name eventually morphed into Santa Claus. The tradition of gift-giving shifted from St. Nicholas’s Day (Dec. 6) to Christmas Eve/Day (Dec. 24–25). Finally, “the definitive depiction of this new and Americanized St. Nicholas [Santa Claus] came in 1823, when The Sentinel of Troy, New York, published an anonymous poem. It began with these memorable lines: ’Twas the night before Christmas, when all thro’ the house, Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse…’ Initially, the poem was given the title, ‘An Account of a Visit from Saint Nicholas.’”30 So the historical roots of Santa Claus are actually Christian, not pagan. That said, I will admit Santa Claus has become secularized and the commercialization of Christmas gift-giving has grown to a point that it overshadows both the birth of Jesus and the real St. Nicholas’ humble generosity.

Conclusion

As you can see, the urban myth about the supposed pagan roots of Christmas is just that…a myth. There is no historical evidence that these (and other) elements of Christmas are grounded in ancient pagan worship. Yet today, many people actually believe Christmas came from a pagan holiday. In fact, some people in the church are abandoning the celebration of Christ’s birth because they have been deceived by the spurious claims of memes like the ones addressed above. To them I would say, “If your primary source of history is social media, you need to get out more and be more discerning.”

As I have shown above, there is no historical evidence that Christmas has pagan roots. Long before pagans were celebrating Sol Invictus on December 25th, Christians had identified it as a possible date of Christ’s birth and were holding a feast in His honor on that day. In truth, we do not really know what day Jesus was born on. However, I do not believe there is anything inherently wrong with celebrating Christmas. In fact, I believe it is a wonderful opportunity to remind people about the incarnation and the reason Jesus came into the world – to seek and to save the lost.

Endnotes:

1 For brevity, I have paraphrased this definition to apply it to things, instead of people. The actual definition is, “A person who is not religious or whose religion is not Judaism, Islam, or especially Christianity.” See https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/pagan (Accessed Sept. 29, 2025).

2 “The Invention of the Electric Guitar, “ Smithsonian. Online: https://invention.si.edu/invention-stories/invention-electric-guitar (Accessed Sept. 29, 2025).

3 Clement of Alexandria, The Stromata, or Miscellanies, 1:21. Online: https://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/clement-stromata-book1.html (Accessed Sept. 29, 2025).

4 Hyppolatus, Commentary on Daniel. 4.23.3. Online: https://www.pergrazia.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/0205_hippolytus_commentary-on-daniel_2010.pdf (Accessed Sept. 29, 2025).

5 I have seen claims that Africanus pinpointed Dec. 25th as the date of Christ’s birth because he believed Jesus died on March 25th, but I cannot find this in the original source material. I believe it may be an urban myth. Perhaps someone confused the anonymous 4th-century homily “On the Solstices and the Equinoxes of the conception and nativity of our Lord Jesus Christ and of John the Baptist” (see footnote 14), which makes this claim, for the work of Africanus. Regardless, here is the reference for what Africanus actually said: Martin Wallraff, ed., lulius Africanus Chronographiae: The Extant Fragments (New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2007), 275.

6 “The Chronography of 354 AD. Part 12: The commemoration of the martyrs.” Online: https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/chronography_of_354_12_depositions_martyrs.htm (Accessed Dec. 6, 2025)

7 “The Chronography of 354 AD. Part 6: the calendar of Philocalus.” Online:https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/chronography_of_354_06_calendar.htm? (Accessed Oct. 3, 2025)

8 Steven Hijmans, “Sol Invictus, the Winter Solstice, and the Origins of Christmas.” Mouseion, Series III, Vol. 3 (2003), p. 385.

9 “The Chronography of 354 AD. Part 6: the calendar of Philocalus.” Online: https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/chronography_of_354_06_calendar.htm? (Accessed Oct. 3, 2025)

10 Steven Hijmans, “Sol Invictus, the Winter Solstice, and the Origins of Christmas.” Mouseion, Series III, Vol. 3 (2003), p. 385.

11 Wes Huff, “Christmas Isn’t Pagan and here’s why,” Dec. 15, 2021, YouTube video, 4:46. Online: https://youtu.be/5zcaQlBbk6s?si=As9LkrPsvXYSxRtU (Accessed Sept. 29, 2025).

12 Macrobius. Saturnalia, Volume I: Books 1-2. Edited and translated by Robert A. Kaster. Loeb Classical Library 510. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 101. https://www.loebclassics.com/view/macrobius-saturnalia/2011/pb_LCL510.101.xml (Accessed Sept. 26, 2025)

13 James Grout, “Saturnalia.” Encyclopaedia Romana. Online: https://penelope.uchicago.edu/encyclopaedia_romana/calendar/saturnalia.html (Accessed Sept. 26, 2025).

14 See the early Christian (ca. fourth century) homily “On the Solstices and the Equinoxes of the conception and nativity of our Lord Jesus Christ and of John the Baptist.” Trans. Isabella., p. 7–9. Online: https://www.roger-pearse.com/weblog/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/De-Solstitiis-et-Aequinoctiis-Image-2022.pdf (Accessed Sept. 29, 2025).

15 Thomas C. Schmit, “Calculating December 25 as the Birth of Jesus in Hippolytus’ Canon and Chronicon.” Vigiliae Christianae 69 (2015), 544-563.

16 Steven Hijmans, “Sol Invictus, the Winter Solstice, and the Origins of Christmas.” Mouseion, Series III, Vol. 3 (2003), p. 396.

17 Commodanius, Instructiones, Poem 12. Online: https://www.thelatinlibrary.com/commodianus/commodianus2.html (Accessed Sept. 29, 2025).

18 Manfred Claus, The Roman Cult of Mithras. Transl. by Richard Gordon. (New York: Routledge, 2001), p. 62.

19 R.O. Faulkner, The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969), p. 236.

20 William Kelly Simpson, ed. The Literature of Ancient Egypt. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003, p. 93 and 95.

21 The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Tammuz.” Encyclopedia Britannica, January 5, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tammuz-Mesopotamian-god.

22 Diane Wolkstein and Samuel Noah Kramer, Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth. (New York: Harper and Row, 1983), p. 31.

23 Maximus of Tyre, Dissertation VII. In Maximus Tyrius, The Dissertations. Transl. by Thomas Taylor. (London: C. Whittingham, 1804), p. 62.

24 Maximus of Tyre, Dissertation VII. In Maximus Tyrius, The Dissertations. Transl. by Thomas Taylor. (London: C. Whittingham, 1804), p. 194.

25 David Bertaina, “Trees and Decorations,” In the Oxford Handbook of Christmas, Ed. Timothy Larson. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), p. 266–267.

26 Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 16.95. Online: https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D16&force=y (Accessed Oct. 2, 25).

27 Herrick, Robert. “Ceremonies for Candlemas Eve.” In Hesperides, 1648. Online: https://poetsonline.blogspot.com/2013/02/a-poem-for-candlemas-eve.html (Accessed Oct. 3, 2025).

28 Jacqueline Simpson and Steve Roud, “Mistletoe,” In A Dictionary of English Folklore. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 242.

29 Adam C. English, “From St Nicholas to Santa Claus,” In The Oxford Handbook of Christmas, Ed. Timothy Larson. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), p. 255.

30 English, p. 258.