In the fourth year of King Hezekiah, which was the seventh year of Hoshea son of Elah, king of Israel, Shalmaneser king of Assyria came up against Samaria and besieged it (2 Kgs 18:9 ESV)

Just as numerous Hebrew kings are mention in Assyrian inscriptions, a number of Assyrian kings are mentioned in the Bible:

- Tilgath-pileser III/Pul – 2 Kings 15:19; 16:7; 1 Chron. 5:26;

- Shalmaneser V – 2 Kings 17:3; 18:9

- Sargon II – Isaiah 20:1

- Sennacherib – 2 Kings 18-19; 2 Chron. 32; Isaiah 36-37

- Esarhaddon – 2 Kings 19:37, Isaiah 37:38; Ezra 4:2

- Ashurbanipal – Ezra 4:10

Having already written an archaeological biography on Tilgath-Pileser III, it is time to turn our attention to his son, Shalmaneser V. Unlike his father, who enjoyed a long reign, Shalmaneser V reigned for only five years from ca. 726-722 BC. Compared to other Assyrian kings, relatively little is known about Shalmaneser’s reign.

Shalmaneser’s Rise to Power

Prior to ascending the throne, Shalmaneser was known by his birth name, Ululayu (sometimes spelled Ululaiu or Ululaju), which means “born in the month of Elul” (the sixth month of the Assyrian calendar, equivalent to August-September).1 As the crown prince, he held an important administrative role in his father’s kingdom, directing affairs in the region west of Assyria.2 Five letters written from Ululayu to his father were discovered at Nimrud and date to this period.3 In one he writes, “It is well with the land of Assur. It is well with the temples. It is well with the fortresses of the king, all (of them). Let the heart of the king my lord be very glad.” 4 Upon his father’s death in 726 BC, he became king and took the throne name Shalmaneser, meaning “the god Salmānu (= ‘friendly one’) is foremost.”5 The Babylonian Chronicle names Shalmaneser as the king of both Assyria and Akkad (Babylonia), which his father had earlier conquered.6

Shalmaneser’s Reign

Information about Shalmaneser’s reign is scarce as there are few inscriptions dating to the years he was in power. The Assyrian Eponym List is a year-by-year description of important events in Assyrian history with each year named after an important person. According to this list, Shalmaneser was engaged in military campaigns in the second, third, and fourth years of his reign (725 – 723 BC), but the tablets are damaged and the place he campaigned each year is missing. An Aramaic ostracon from Assur, dating from a later time period, notes that Shalmaneser deported captives from Bit-Adini,7 so perhaps that would account for one of his campaigns. The fact that Shalmaneser ruled as both king of Assyria and Babylon, and participated in various military campaigns indicates that he was following the polices of his father.

Only a few other artifacts bearing Shalmaneser’s name have been discovered. Sixteen bronze weights, shaped like crouching lions, were discovered in the Northwest palace at Nimrud. They bear the name Shalmaneser, and since they were discovered with other weights attributed to Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon II, they undoubtedly refer to Shalmaneser V and not one of the other kings of the same name.8 A golden bowl belonging to Shalmaneser’s queen, Banitu, was discovered along with other artifacts in a sarcophagus in a tomb under Room 49 in the Northwest Palace. It bears an inscription that reads, “Belonging to Banitu, queen of Shalmaneser, king of Assyria.”9

Shalmaneser’s Palace

While Shalmaneser was king, he ruled from the palace of the Assyrian kings at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu/ Calah) which is located about 30 km southeast of Mosul in modern-day Iraq. The Northwest Palace was constructed by Ashurbanipal II (ca. 883–859 BC), as the royal residence and administrative center of the empire. This palace was 120 x 200 meters in size; its walls were lined with stone reliefs and its entrances were guarded by lamassu, giant human-headed, winged bull figures.10 When Shalmaneser’s successor Sargon II became king, he built a new royal city and palace which he called Dûr-Sharrukin, the Fortress of Sargon

Sadly, in 2014, northern Iraq fell under the control of ISIS and the terrorist group began to intentionally destroy historical sites throughout the region. In April 2015, the group vandalized and destroyed parts of the Northwest Palace using heavy equipment and barrel bombs, which had been placed in front of the remaining stone reliefs. Before-and-after Google Earth images show the extent of the damage to the palace from which Shalmaneser once ruled.

Shalmaneser and Israel

Shalmaneser is best known for his attack on Israel in 722 BC, an event recorded both in the Bible and in a Babylonian text. According to the Bible, Shalmaneser attacked Israel when King Hoshea withheld his tribute, and turned to So, king of Egypt for help in his rebellion.

Against him came up Shalmaneser king of Assyria. And Hoshea became his vassal and paid him tribute. But the king of Assyria found treachery in Hoshea, for he had sent messengers to So, king of Egypt, and offered no tribute to the king of Assyria, as he had done year by year. Therefore the king of Assyria shut him up and bound him in prison. Then the king of Assyria invaded all the land and came to Samaria, and for three years he besieged it. In the ninth year of Hoshea, the king of Assyria captured Samaria, and he carried the Israelites away to Assyria and placed them in Halah, and on the Habor, the river of Gozan, and in the cities of the Medes. (2 Kgs 17:3-6 ESV)

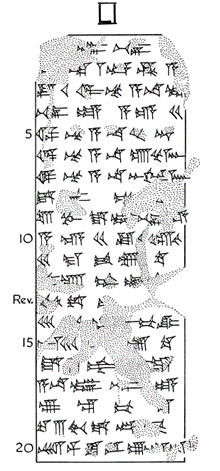

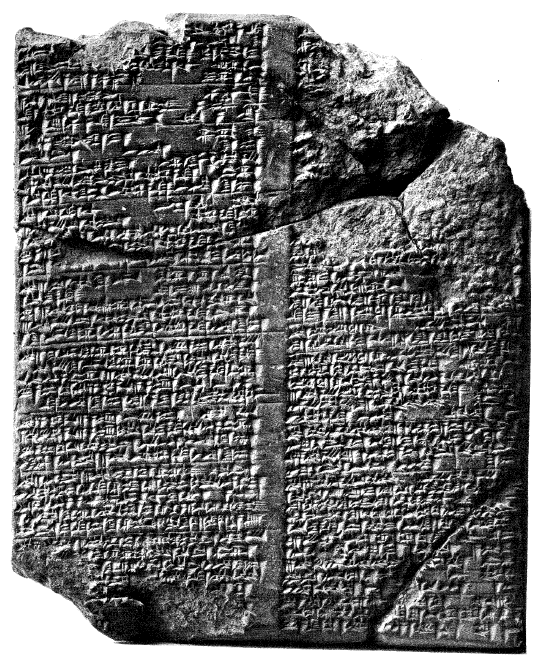

The Babylonian Chronicle (ABC 1) records Shalmaneser’s reign and his attack on Israel (Samaria) in just a few lines:

On the twenty-fifth of the month Tebêtu, Šalmaneser in Assyria and Akkad ascended the throne. He ravaged Samaria. The fifth year:note Šalmaneser went to his destiny in the month Tebêtu. For five years Šalmaneser ruled Akkad and Assyria.11

Despite this testimony from the Bible and the Babylonian chronicle, Sargon II boasted in numerous inscriptions that he had conquered Israel.12 How does one account for this discrepancy. There are at least two plausible solutions to this problem:

- The conquest of Israel was begun under Shalmaneser, and finished under Sargon. Thus, Shalmaneser is named as the Assyrian king who invaded the land and imprisoned Hoshea (2 Ki 17:3-4), while Sargon is the unnamed “king of Assyria” who captured Assyria and carried off the Israelites (2 Ki 17:6). This would be similar to the five-year siege of Tyros, which was begun by Shalmaneser and ended during the reign of Sargon.13

- Shalmaneser conquered Israel, but died shortly afterward. Sargon later took credit for the conquest in his inscriptions. Kenneth Kitchen explains:

“Following Shalmaneser’s very brief reign, which ended before any account of his last year could be monumentalized, Sargon II replaced him…and subsequently claimed the capture of Samaria for himself, much later in his reign. This was certainly a propaganda exercise, to cover the gap in military successes that would otherwise disfigure the accounts of his reign. The mere three months of his “accession year” were not adequate to run a campaign, nor the season suitable; and internal strife occupied the first year of his reign. So the later annalists had to cover this over by attributing Shalmaneser’s capture of Samaria to Sargon.”14

Shalmaneser’s Death

The circumstances surrounding Shalmaneser’s death are unknown. The Babylonian Chronicle (above) merely states that he “went to his destiny.” It has long been assumed that Shalmaneser was killed in the rebellion that brought Sargon, a usurper, to the throne. This theory is usually based upon the fact the new king took the throne name Sargon, meaning “legitimate one” which is seen as an attempt to justify his kingship. Moreover, the Assur Charter of Sargon paints a negative picture of Shalmaneser, claiming that the god Assur overthrew his predecessor because Shalmaneser did not revere the city of Assur and imposed forced labor upon its citizens.15 This inscription seems to be a pro-Sargon, anti-Shalmaneser piece of propaganda intended to legitimize Sargon’s rise to power.

However, French historian Josette Elayi maintains, “Currently the opinion that Sargon was not a usurper is better supported. In fact, the filiation is indicated in two Sargon inscriptions where he was clearly presented as the son of Tiglath Pileser III, king of Assyria. He also referred to his ‘royal fathers’ in the so-called Borowski Stela, probably originating from Hamath.”16 She believes Shalmaneser died of natural causes, and his brother Sargon was the logical choice to became king.

Whatever the cause, Shalmaneser V died in 722 BC, having reigned only five years.

Conclusion

Despite his short reign and a complete lack of royal inscriptions, the one key event in his reign is attested historically: Shalmaneser’s devastating attack on the northern kingdom of Israel is described both in the Both and in the Babylonian. Sargon’s boasts to have been the conqueror of Israel have plausible explanations. Until his royal archive is found or more contemporary inscriptions shed light on his reign, Shalmaneser V will remain a somewhat enigmatic biblical figure.

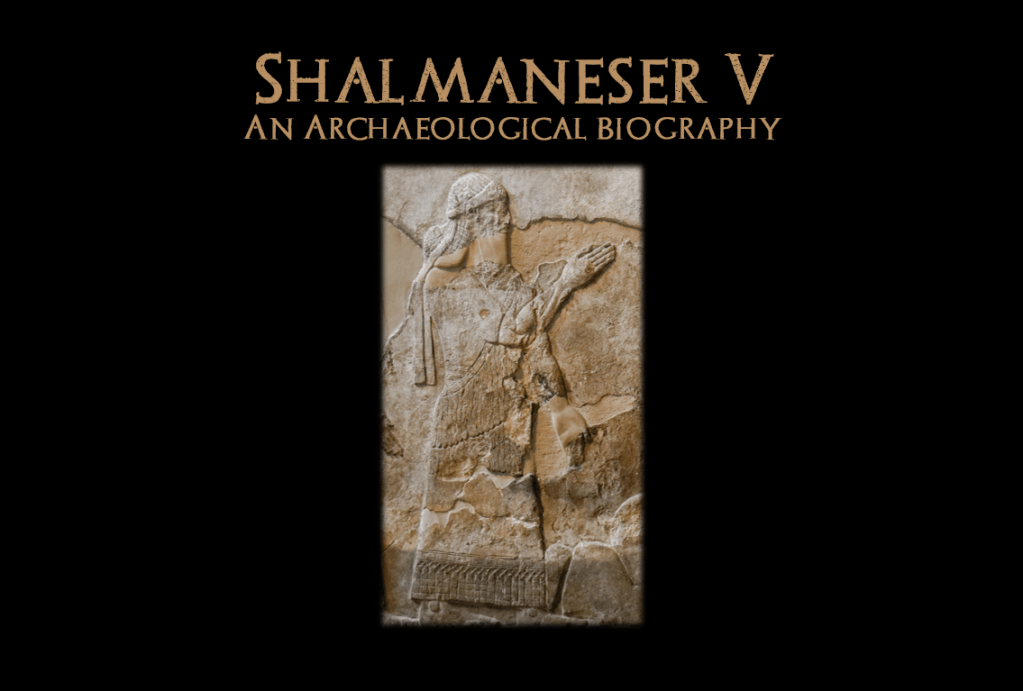

Cover: A relief from the Northwest Palace at Nimrud likely depicting Shalmaneser V as the crown prince known then as Ululayu. Photo: Todd Bolen / BiblePlaces.com

Endnotes:

1 Karen Radner, “Shalmaneser V, king of Assyria (726-722 BC)”. UCL Assyrian empire builders. Online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/essentials/kings/shalmaneserv/ (Accessed April 18, 2024).

2 H. D. Baker, ‘Salmanassar V.’, in M. P. Streck et al. (eds.), Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 11/7-8, Berlin: de Gruyter, 2008, 586. Online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/downloads/baker_rla2008.pdf (Accessed April 18, 2024).

3 Karen Radner, “Shalmaneser V, king of Assyria (726-722 BC)”. UCL Assyrian empire builders. Online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/essentials/kings/shalmaneserv/ (Accessed April 18, 2024).

4 H. W. F. Saggs, “The Nimrud Letters, 1952: Part V.” Iraq, Vol. 21, No. 2 (Autumn, 1959), 159. https://doi.org/10.2307/4199658 (Accessed April 18, 2024).

5 Keiko Yamada and Shiego Yamada, “Shalmaneser V and His Era, Revisited”. In Baruchi-Unna, Amitai; Forti, Tova; Aḥituv, Shmuel; Ephʿal, Israel; Tigay, Jeffrey H. eds. Now It Happened in Those Days”: Studies in Biblical, Assyrian, and Other Ancient Near Eastern Historiography Presented to Mordechai Cogan on His 75th Birthday. Vol. 2. (Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 2017), 388. Online: https://www.academia.edu/35496181 (Accessed April 19, 2024).

6 H. D. Baker, ‘Salmanassar V.’, in M. P. Streck et al. (eds.), Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 11/7-8, Berlin: de Gruyter, 2008, 586. Online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/downloads/baker_rla2008.pdf (Accessed April 18, 2024).

7 Baker, 587.

8 Hayim Tadmor and Shigeo Yamada, The Royal Inscriptions of Tiglath-pileser III (744–727€BC), and Shalmaneser V (726–722 BC), Kings of Assyria. (Winona Lake, Eisenbrauns, 2011), 171.

9 Tadmor and Yamada, 188.

10 Michael Danti, Scott Branting, Tate Paulette, and Allison Cuneo, “Special Report: On The Destrution of the Northwest Palace at Nimrud.” ASOR, May 5, 2015. Online: https://www.asor.org/chi/reports/special-reports/on-the-Destruction-of-the-Northwest-Palace-at-Nimrud (Accessed April 19, 2024).

11 “ABC 1 (From Nabû-Nasir to Šamaš-šuma-ukin),” Livius.org. Online: https://www.livius.org/sources/content/mesopotamian-chronicles-content/abc-1-from-nabu-nasir-to-samas-suma-ukin/ (Accessed April 19, 2024).

12 Sargon claims to have defeated and deported the Israelites from Samaria in the Khorsabad Summary Inscription, the Calah summary Inscription, and the Khorsabad Annals. See Mordecai Cogan, The Raging Torrent: Historical Inscriptions from Assyria and Babylonia Relating to Ancient Israel. (Jerusalem: Carta, 2015), 90–101.

13 H.J. Katzendstein, The History of Tyre, as quoted in Keiko Yamada and Shiego Yamada, “Shalmaneser V and His Era, Revisited”. In Baruchi-Unna, Amitai; Forti, Tova; Aḥituv, Shmuel; Ephʿal, Israel; Tigay, Jeffrey H. eds. Now It Happened in Those Days”: Studies in Biblical, Assyrian, and Other Ancient Near Eastern Historiography Presented to Mordechai Cogan on His 75th Birthday. Vol. 2. (Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 2017), 387. Online: https://www.academia.edu/35496181 (Accessed April 19, 2024).

14 K. A. Kitchen, On The Reliability of the Old Testament. (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2006), 39.

15 Keiko Yamada and Shiego Yamada, “Shalmaneser V and His Era, Revisited”. In Baruchi-Unna, Amitai; Forti, Tova; Aḥituv, Shmuel; Ephʿal, Israel; Tigay, Jeffrey H. eds. Now It Happened in Those Days”: Studies in Biblical, Assyrian, and Other Ancient Near Eastern Historiography Presented to Mordechai Cogan on His 75th Birthday. Vol. 2. (Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 2017), 424. Online: https://www.academia.edu/35496181 (Accessed April 19, 2024).

16 7 Josette Elayi, Sargon II, King of Assyria. (Atlanta, SBL Press, 2017), 27.

[…] In the fourth year of King Hezekiah, which was the seventh year of Hoshea son of Elah, king of Israel, Shalmaneser king of Assyria came up against Samaria and besieged it (2 Kings 18:9). The Bible Archeology Report puts together wonderful biographies of biblical characters based on archeological discoveries that corroborate the account in Scripture. Here is the biography of Assyrian King Shalmaneser V. […]