Rehum the commanding officer and Shimshai the secretary, together with the rest of their associates-the judges and officials over the men from Tripolis, Persia,Erech and Babylon, the Elamites of Susa, and the other people whom the great and honorable Ashurbanipal deported and settled in the city of Samaria and elsewhere in Trans-Euphrates. (Ez 4:9-10 NIV)

In this blog, we turn our attention to the final Assyrian king named in the Bible: the “great and honorable Ashurbanipal.” You can find my articles about the other biblical Assyrian kings here:

- Tilgath-pileser III/Pul – 2 Kings 15:19; 16:7; 1 Chron. 5:26;

- Shalmaneser V – 2 Kings 17:3; 18:9

- Sargon II – Isaiah 20:1

- Sennacherib – 2 Kings 18-19; 2 Chron. 32; Isaiah 36-37

- Essarhaddon – Ezra 4:1-2

Identifying Ashurbanipal

In Ezra 4, Rehum, the commanding officer, and Shimshai, the secretary over the Persian province called “Beyond-the-River,” write a letter to King Artaxerxes to object that the Jews are rebuilding Jerusalem, which they describe as “that rebellious and wicked city” (Ez 4:12). They specifically mention that they are governing people in the area formerly known as Judah and Samaria, whom Ashurbanipal settled from Babylon and Elam, among other places.

Actually, the name used in Ezra 4:10 is Onsappar, as it is translated in the ESV and NASB. Onsappar is generally considered to be a corruption of Ashurbanipal, the last great Assyrian king. Alan Millard proposed several possible linguist ways the Assyrian king’s name could have morphed into Onsappar and concluded, “Identification with Ashurbanipal can hardly be doubted.”1 Historically, this identification fits, since Ashurbanipal is known to have waged numerous campaigns against the Elamites2 and he also had to put down a significant revolt led by his brother who was king of Babylon.3 It is probable that Ashurbanipal would have relocated these conquered peoples to the area of Judah and Samaria, as previous Assyrian kings, such as Sargon II, did.

Ashurbanipal’s Reign

Ashurbanipal’s father, Esarhaddon, seems to have been intent on ensuring a smooth transition of power, unlike his own turbulent ascension. As such, four years before he died the Assyrian king appointed his successors, by splitting the empire between his two sons: Ashurbanipal was to become king of Assyria and Shamash-shum-ukin would inherit the throne of Babylon.4 While this arrangement may have made sense to Esarhaddon at the time, it would eventually lead to a rebellion led by Shamash-shum-ukin.

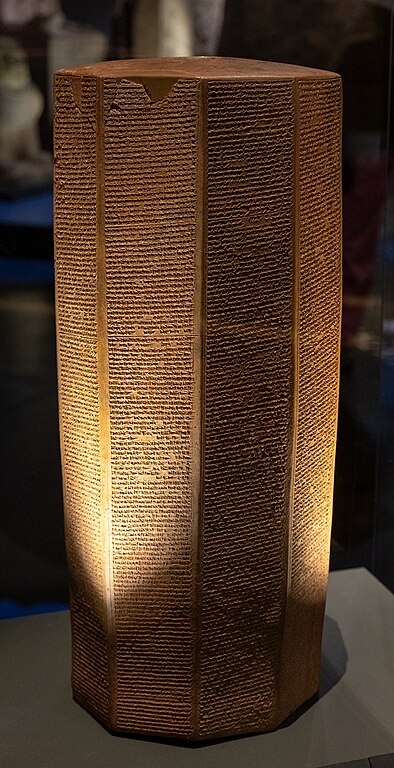

Ashurbanipal’s own inscriptions affirm that he was his father’s selection as heir to the throne and credits this as the will of the Assyrian gods. On the Rassam Cylinder he wrote: “I (am) Assurbanipal, offspring (creature) of Assur and Belit, the oldest prince of the royal haram, whose name Assur and Sin the lord of the tiara, have named for the kingship from the earliest days, whom they formed in his mother’s womb, for the rulership of Assyria…Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, the father who begot me, respected the word of Assur and Belit-ile (the Lady of the gods), his tutelary (divinities), when they gave command that I should exercise sovereignty.”5

Ashurbanipal ascended the throne of Assyria upon his father’s death in 669 BC and ruled until 631 BC.

According to Sami Said Ahmed, “Ashurbanipal came to the throne in a time of uneasiness. Egypt, Tyre, and Arvad were in open revolt and an Assyrian army was already on its way to deal with the rebels.”6 In his annals, Ashurbanipal claims to have subdued the kings along the Mediterranean coast before sweeping into Egypt to quell the rebellion there.7

Assyrian’s historic enemy was Elam, and the Elamites attacked Assyria, despite the fact that Ashurbanipal claims to have sent aid to them during a severe famine in their land. He wrote, “On my sixth campaign, I marched against Urtaku, the king of the land of Elam, who did not remember the kindness of the father who engendered me nor did he respect my friendship. After famine occurred in the land Elam and hunger had set in, I set to him grain…”8 This would not be the last of the Elam’s rebellions nor Ashurbanipal’s campaigns against Elam, especially when the Elamites allied themselves with his brother in his rebellion.

Shamash-shum-ukin had been given the throne of Babylonia, no doubt with the intent that he would rule southern Mesopotamia. However, important cities like Nippur, Ur, and Uruk considered Ashurbanipal to be their ruler and virtually ignored Šamaš-šuma-ukīn.9 Moreover, Ashurbanipal had informers report on his brother’s activity and required Shamash-shum-ukin to report on all matters to the king of Assyria.10 The situation eventually caused Shamash-shum-ukin to revolt against his brother in 652 BC. Ashurbanipal records that the king of Elam “accepted bribe(s) from the hands of the messengers of Shamash-shum-ukin— (my) unfaithful brother, my enemy — he sent his forces with them to fight with my troops, my battle troops who were marching about in Kardunias (Babylonia) (and) subduing Chaldea.”11 After a two-year siege Babylon surrendered and Shamash-shum-ukin died under mysterious circumstances. Ashurbanipal stated that “the god who created me, the god Assur determined for him a cruel death; he consigned him to a conflagration.”12

Given the constant problems with the Elamites and Babylonians, it is hardly surprising Ashurbanipal relocated these conquered peoples to the region of peoples to the area of Judah and Samaria (Ez 4:9-10).

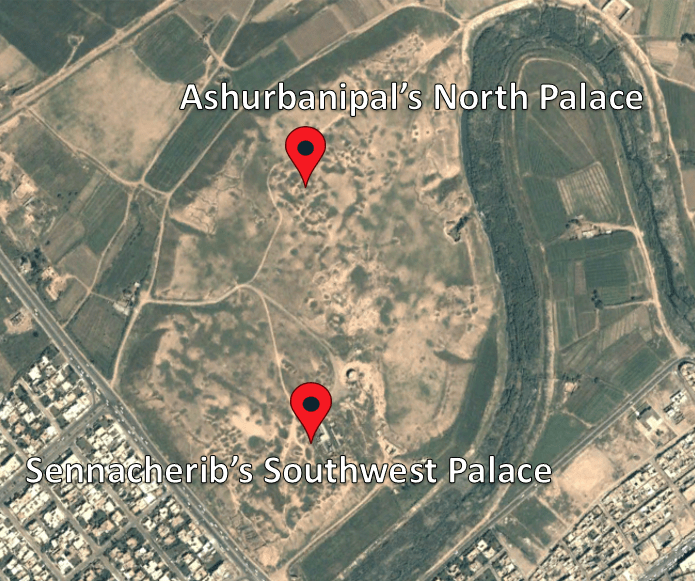

Ashurbanipal’s Palace

Ashurbanipal’s grandfather, Sennacherib, constructed his palace on the south-west part of the main hill called Kuyunjik at Ninevah. His father, Esarhaddon, built his palace on another mound at Nineveh called Nabī Yūnus. For his part, Ashurbanipal returned to the main hill of Kuyunjik to build his palace in the northern section. It was discovered on Dec. 20, 1853 by Hormuzd Rassam. In his book, Asshur and the Land of Nimrod, Rassam describes how he discovered the palace while digging at night. He was digging at night because permission had been granted to another scholar, a Frenchman named M. Place, to dig in the northern corner. This irked Rassam because it was the common etiquette at the time that no agent of another museum was to intrude on sites already being excavated by another. Rassam had been digging at Kuyunjik on behalf of the British Museum and felt he had the prior claim to the site. So, after a year of inactivity by M. Place, Rassam began digging at night, in hopes of finding something of significance, which would allow him to be the one to exclusively excavate the northern portion of the site. Rassam describes his discovery this way: “It was on the night of the 20th of December, 1853, that I commenced to examine the ground in which I was fortunate enough to discover, after three nights’ trial, the grand palace of Assur-bani-pal, commonly known by the name of Sardanapalus….the remnant of the sculptured wall discovered was on a low level running upward, and this fact alone was enough to convince an experienced eye that the part of the building I had hit upon was an ascending passage leading to the main building….after three or four hours’ hard labor [we] were rewarded by the first grand discovery of a beautiful bas-relief in a perfect state of preservation, representing the king, who was afterwards identified as Assur-bani-pal, standing in a chariot, about to start on a hunting expedition, and his attendants handing him the necessary weapons for the chase.”13

News of the discovery spread quickly bringing M. Place came from Khorsabad, where he was excavating. He was displeased that Rassam had excavated in his area. Rassam tried to reason with him that the British had the prior claim to the site, but M. Place, while publicly congratulating Rassam, hinted that he would be protesting this infringement. Later, in his own Book, Place ignored Rassam and implied that it was the French who made the discovery.14 This was likely because the French had excavated part of Ashurbanipal’s palace, albeit only after its discovery and excavation by the British. Following the British and French excavations of the 19th century, the North Palace of Ashurbanipal was again excavated by Campbell Thompson in 1904-05.

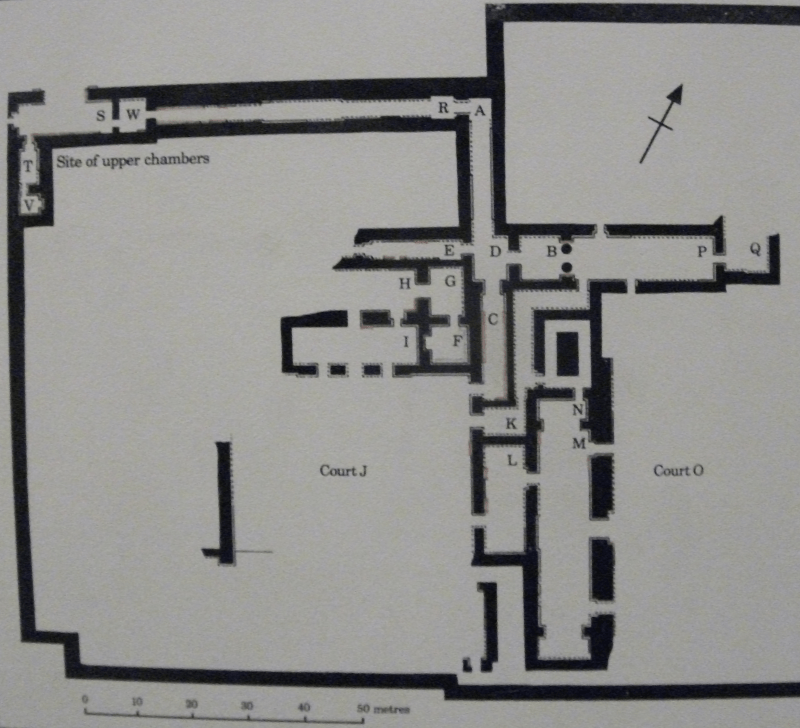

In all, only about half of Ashurbanipal’s palace was excavated. It appears that it was smaller than Sennacherib’s Southwest Palace, but that it followed the typical layout of an Assyrian palace. It appears the palace was approximately 120m wide x 250m long.15 It was constructed around two main courtyard: the Throne Room Courtyard (O) and the Inner Courtyard (J).16 Many of the famous lion hunting reliefs from Ashurbanipal’s palace came from rooms A, C and E, although mostly from room C.17 While Ashurbanipal probably completed the construction of his palace in 643 BC, it did not last long, as it was destroyed in 612 BC, likely when the Babylonians conquered Ninevah.18

Ashurbanipal’s Library

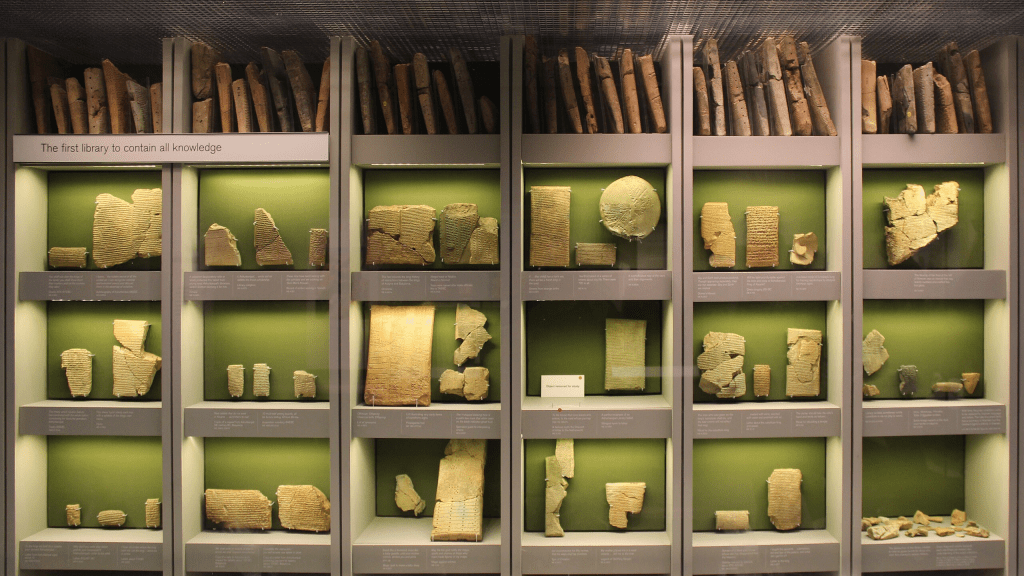

One of the great discoveries within Ashurbanipal’s palace was the library. Actually, the Library of Ashurbanipal is the name given to the collection of some 30,000 cuneiform tablets discovered both in his palace by Hormuzd Rassam and earlier by Austin Henry Layard in the palace of Sennacherib. Both palaces were destroyed by fire which hardened the clay tablets, preserving them until today.

Within the library were literary, religious, medical, historical, and legal texts. The famous Mesopotamian creation myth, the Epic of Gilgamesh was first discovered in Ashurbanipal’s library. The importance of this collection of documents is explained by Jonathan Taylor, the Middle East Curator at the British Museum: “Before the discovery of the Library, almost everything we knew about ancient Assyria came from stories in the Bible or classical historians. With the discovery of the Library, thousands of cuneiform texts were recovered, telling the Assyrians’ story in their own words. From these we can follow court intrigues, listen in on secret intelligence reports, follow rituals step-by-step, hear the words of hymns and prayers, and thumb through medical handbooks, as well as reading in incredible detail about the deeds of the kings.”19

Conclusion

While much is known about Ashurbanipal’s reign, particularly in the early years, there are very few extant sources for the final decade of his reign (ca. 642-631).20 An inscription by his son, Ashur-etil-ilani, seems to indicate his father died of natural causes.21 With Ashurbanipal’s death in 631 BC, the Assyrian empire began to decline and its capital, Nineveh, would fall to the Babylonians less than two decades later. Due to his military campaigns, his building projects, and his dedication to learning, Ashurbanipal is often regarded as the last great Assyrian king. It would seem that way he is described in the Bible -“the great and honorable Ashurbanipal” – is indeed fitting.

Cover Photo: A.D. Riddle / Bibleplaces.com

Endnotes

1 A.R. Millard, “Assyrian Royal Names in Biblical Hebrew.” Journal of Semitic Studies XXI (1-2), p. 11. Online: https://doi.org/10.1093/jss/XXI.1-2.1 (accessed Aug. 10, 2024).

2 A. Kirk Grayson, “Onsappar,” The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. D.N. Freedman. (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 6545.

3 Jamie Novotny and Joshua Jeffers, The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal (668-631 BC), Aššur-etel-ilāni (630-627 BC), and Sîn-šarra-iškun (626-612 BC), Kings of Assyria, Part 1. (University Park: Eisenbrauns, 2018), 20-23.

4 Shana Zaia, “My Brother’s Keeper : Assurbanipal versus Samas-suma-ukin,” Journal of ancient Near Eastern History, vol. 6 , no. 1, 2019. p. 20. https://doi.org/10.1515/janeh-2018-2001 (Accessed Aug. 10, 2024).

5 Daniel David Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia, Vol II. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1927), 291

6 Sami Said Ahmed, Southern Mesopotamia in the Time of Ashurbanipal. (The Hague: Mouton & Co. N.V. Publishers, 1968), 29.

7 Daniel David Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia, Vol II. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1927), 292-295.

8 Jamie Novotny and Joshua Jeffers, The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal (668-631 BC), Aššur-etel-ilāni (630-627 BC), and Sîn-šarra-iškun (626-612 BC), Kings of Assyria, Part 1. (University Park: Eisenbrauns, 2018), 66.

9 Sami Said Ahmed, Southern Mesopotamia in the Time of Ashurbanipal. (The Hague: Mouton & Co. N.V. Publishers, 1968), 80.

10 Ahmed, 87.

11 Jamie Novotny and Joshua Jeffers, The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal (668-631 BC), Aššur-etel-ilāni (630-627 BC), and Sîn-šarra-iškun (626-612 BC), Kings of Assyria, Part 1. (University Park: Eisenbrauns, 2018), 74.

12 Novotny and Jeffers, 133.

13 Hormuzd Rassam, Assur and the Land of Nimrod. (Cincinnati: Curtis & Jennings, 1897), 25-26.

14 Rassam, 27.

15 “The North Palace,” https://www.learningsites.com/Nineveh/NP_Nineveh_home.php# (Accessed Aug. 16, 2024).

16 David Kertai, The Architecture of Late Assyrian Royal Palaces. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 173-176.

17 R. D. Barnett, Sculptures from the North Palace of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh (668 – 627 B.C.). (London: Trustees of the British Museum; British Museum Publications, 1976), 12.

18 “The North Palace,” https://www.learningsites.com/Nineveh/NP_Nineveh_home.php# (Accessed Aug. 16, 2024).

19 Jonathan Taylor, “A Library Fit For A King.” British Museum Blog. https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/library-fit-king (Accessed Aug. 21, 2024).

20 Jamie Novotny and Joshua Jeffers, The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal (668-631 BC), Aššur-etel-ilāni (630-627 BC), and Sîn-šarra-iškun (626-612 BC), Kings of Assyria, Part 1. (University Park: Eisenbrauns, 2018), 1.

21 Sami Said Ahmed, Southern Mesopotamia in the Time of Ashurbanipal. (The Hague: Mouton & Co. N.V. Publishers, 1968), 121.

Thanks Bryan. Some scholars have argued that the “Nebuchadnzzar” of the book of Judith actually corresponds well with Ashurbanipal. Wiki includes that proposal. Curious, what do you think?