“And I, Artaxerxes the king, make a decree to all the treasurers in the province Beyond the River: Whatever Ezra the priest, the scribe of the Law of the God of heaven, requires of you, let it be done with all diligence…” (Ezra 7:21)

Five Persian kings are named in the Bible: Cyrus (2 Chr 36:22-23), Darius I (Ezra 4:5), Xerxes/Ahasuerus (Esther 1:1-3), Artaxerxes (Ezra 7:1-22), and “Darius the Persian,” either Darius II or III (Neh. 12:22). Having written archaeological biographies on the first three of the Persian kings name in the Bible, I now turn my attention to Artaxerxes.

Artaxerxes is the Greek form of the Old Persian Artaxšaçā (𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎠), which comes from the root words arta (justice) and khshatra (kingdom), meaning “having a kingdom of justice” or “having a just rule.”1 He was nicknamed “long-armed” (Greek, markocheir; Latin, Longimanus) because, according to Plutarch, his right hand was longer than his left.2

The Ascension of Artaxerxes

Artaxerxes I was the son of Xerxes/Ahasuerus and eventually won the Persian throne in the aftermath of his father’s murder. According to the Greek historian Diodorus, Artabanus, a Persian official, killed Xerxes in his sleep and then blamed the king’s oldest son, Darius. Artabanus convinced young Artaxerxes to kill his brother to take the throne, even though he planned to seize the throne for himself. He writes:

Artaxerxes fell in with the advice and at once, with the help of the body-guard, slew his brother Darius. And when Artabanus saw how his plan was prospering, he called his own sons to his side and crying out that now was his time to win the kingship he strikes Artaxerxes with his sword. Artaxerxes, being wounded merely and not seriously hurt by the blow, held off Artabanus and dealing him a fatal blow killed him. Thus Artaxerxes, after being saved in this unexpected fashion and having taken vengeance upon the slayer of his father, took over the kingship of the Persians.3

Artaxerxes became king in 465 BC and ruled until 424 BC. His reign serves as the backdrop to much of the books of Ezra and Nehemiah in the Old Testament.

The Kingdom of Persia Under Artaxerxes

Early in his reign, Artaxerxes had to contend with numerous rebellions, the most serious of which was the revolt in Egypt which lasted almost a decade. According to Thucydides, a Lybian king named Inaros who ruled near the Egyptian border, “caused a revolt of almost the whole of Egypt from King Artaxerxes, and placing himself at its head, invited the Athenians to his assistance.”4 The Greek city-states had formed an alliance, called the Delian League, which was led by Athens. They came to the assistance of the Egyptians, initially defeating the Persian satrap. After a prolonged struggle, Persian rule was finally restored by Megabyzus, the satrap of Syria, who later rebelled against Artaxerxes, before being reconciled again to the Persian king. Eventually, both the Greeks and the Persians, weary of continual battle, negotiated the Peace of Callias in 449 BC.5

Biblical history ties into this period in two interesting ways. The fourth chapter of the Book of Ezra describes various adversaries opposing the rebuilding in Jerusalem. There we read, “In the days of Artaxerxes, Bishlam and Mithredath and Tabeel and the rest of their associates wrote to Artaxerxes king of Persia. The letter was written in Aramaic and translated. Rehum the commander and Shimshai the scribe wrote a letter against Jerusalem to Artaxerxes the king” (Ez. 4:7-8a ESV). Artaxerxes responded by ordering the work on the city to cease (Ez. 4:21). However, three chapters later, Ezra leaves for Jerusalem with Artaxerxes’ blessing and command to take from the treasury whatever was needed for the Temple (Ez. 7:6-26). Later still, Artaxerxes allows Nehemiah to return to Jerusalem to rebuild the city walls (Neh. 2:1-8). How does one explain the initial command of Artaxerxes to cease work on Jerusalem and his change of heart? The historical background of the Egyptian revolt and rebellion of Megabyzus provides an explanation. Bible scholar Edwin Yamauchi explains: “If the events of Ezra 4:7-23 took place during the Egyptian revolt, Artaxerxes would have probably been suspicious of the building activities in Jerusalem. How then could the same king have commissioned Nehemiah to rebuild the walls of the city in 445 [BC]? By then both the Egyptian revolt and the rebellion of Megabyzus had been resolved.”6

Furthermore, Artaxerxes’ commission for Ezra to return to Jerusalem to teach the people the Law of Yahweh fits with known Persian policy. For example, Darius I commissioned an Egyptian Priest named Udjahorresnet to restore the worship and shrine at Sais and to teach the laws of Egypt.7 It appears that once the rebellions had been quelled, Artaxerxes was eager to implement Persian policy to pacify the local people.

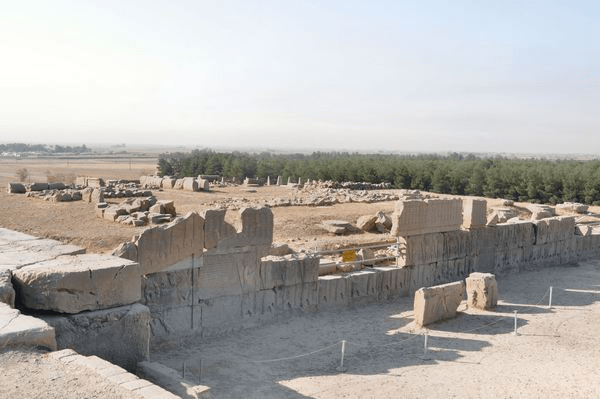

Artaxerxes’ Palace at Persepolis

Darius I, grandfather of Artaxerxes, built a new capital for the Achaemenid Empire at Persepolis and constructed a magnificent palace there. During is own reign, Artaxerxes continued building Persepolis. He finished the Throne Hall that his father had begun. An inscription on a stone slab discovered there reads, “King Artaxerxes says: My father, king Xerxes, laid the foundations of this palace. With the protection of Ahuramazda, I, king Artaxerxes, have finished it.”8 There were two entrances to the hall with reliefs of a king (likely Artaxerxes) seated upon his throne.9 Artaxerxes also constructed a palace for himself at Persepolis. Little remains of this palace, however, and the ruins are overshadowed by the more impressive ruins of the Apadana (audience hall) and Throne Hall.

Artaxerxes and Nehemiah

The first chapter of the Book of Nehemiah is set at Susa, the winter residence of the Persian kings. It was built by Darius I, and is the setting for the book of Esther. Nehemiah is introduced as the cup-bearer to King Artaxerxes (Neh. 1:11) while serving him at the citadel of Susa (Neh. 1:1). The remains of the palace where Nehemiah served Artaxerxes is located in modern-day Iran and is visible from Google Earth.

As cupbearer, Nehemiah was an official in the court of Artaxerxes and had numerous important roles. Xenophon describes Persian cupbearers this way: “Now, it is a well known fact that the king’s cupbearers, when they proffer the cup, draw off some of it with the ladle, pour it into their left hand, and swallow it down—so that, if they should put poison in, they may not profit by it.”10 A silver drinking bowl in the British Museum bears the inscription, “Artaxerxes, the great king, king of kings, king of countries, son of Xerxes the king, of Xerxes [who was] son of Darius the king, the Achaemenian, in whose house this drinking cup/saucer was made.”11 Nehemiah may have used a drinking bowl such as this in his daily duties. Ancient Cupbearers did more than just test the king’s wine for poison though: “Now Ahi′kar was cupbearer, keeper of the signet, and in charge of administration of the accounts, for Esarhad′don had appointed him second to himself” (Tobit 1:22 RSV). In short, cupbearers were important officials in the courts of the Persian kings.

Jan. 2009

Artaxerxes eventually appointed Nehemiah to be the governor over the province of Yehud/Judah (Neh. 5:14). One of Nehemiah’s first tasks was to ensure the walls of Jerusalem were rebuilt. Given the revolts Artaxerxes had already had to put down the in the west, he no doubt valued having a trusted official such as Nehemiah overseeing the region. Numerous Persian-era coins have been discovered that bear the inscription Yehud, the Persian name for the province of Judah.12

Death of Artaxerxes

Artaxerxes reigned for forty years and then died, apparently of natural causes. He was buried in a monumental tomb that had been carved into a cliff at Naqsh-e Rustam northwest o Persepolis. The second tomb from the left is usually identified as the one belonging Artaxerxes

Conclusion

The reign of Artaxerxes I provides the background to the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. Understanding the political situation in the Persian empire during the fifth century BC illuminates the account of the return of the exiles to rebuild Jerusalem.

COVER PHOTO: Diego Delso / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0

ENDNOTES:

1 Ewin M. Yamauchi, Persia and the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1990), p. 241.

2 Plutarch, Artaxerxes 1. Online: https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Artaxerxes*.html (Accessed Oct. 7, 2024).

3 Diadorus, 11.69.5-6. Online: https://topostext.org/work/134 (Accessed Oct. 7, 2024).

4 Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War 1.104.1-2. Online: https://anastrophe.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/perseus/citequery3.pl?dbname=GreekNov21&getid=2&query=Thuc.%201.104.1 (Accessed Oct. 9, 2024).

5 Ewin M. Yamauchi, Persia and the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1990), p. 251-252.

6 Yamauchi, p. 251.

7 Yamauchi, p. 256-257.

8 “A1Pb,” Livius.org. Online: https://www.livius.org/sources/content/achaemenid-royal-inscriptions/a1pb/ (Accessed Oct. 22, 2024).

9 Ewin M. Yamauchi, Persia and the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1990), p. 364.

10 Xenophon, Cyropaedia 1.3.9. Online: https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Xen.%20Cyrop.%201.3.9&lang=original (Accessed Oct. 22, 2024).

11 “Bowl,” The British Museum. Online: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1994-0127-1 (Accessed Oct. 22, 2024).

12 David Hendin, Guide to Biblical Coins, Fifth Edition. (Nyack: Amphora, 2010), p. 113.