In the thirty-seventh year of the exile of Jehoiachin king of Judah, in the year Evil-Merodach became king of Babylon, he released Jehoiachin from prison on the twenty-seventh day of the twelfth month. He spoke kindly to him and gave him a seat of honor higher than those of the other kings who were with him in Babylon. So Jehoiachin put aside his prison clothes and for the rest of his life ate regularly at the king’s table. Day by day the king gave Jehoiachin a regular allowance as long as he lived. (2 Kings 25:27–30)

The Neo-Babylonian king, Amēl-Marduk (biblical Evil-Merodach) is only mentioned twice in Scripture (in 2 Kgs 25:27–30 and the parallel passage, Jer 52:31–34), both times in connection with the restoration of Jehoiachin, king of Judah.

Evil-Merodach’s Reign

Amel-Marduk was the son and successor of King Nebuchadnezzar. According to the Uruk Kings List, he reigned for just two years (c. 561–560 BC).1 The ancient historian Berossus wrote a history of Babylon in which he briefly summarized Evil-Merodach’s reign. He reported a negative impression of Evil-Merodach and described how he was murdered by his brother-in-law, Neriglissar, who then seized the Babylonian throne for himself. Berossus also confirmed that Evil-Merodach reigned for just two years. He wrote:

“Nabouchodonosoros [Nebuchadnezzar] fell ill after he had begun the aforementioned walls and died. He had been king for 43 years. His son Eveilmaradouchos [Evil-Merodach]became master of the kingdom. Because he managed affairs in a lawless and outrageous fashion he was plotted against and killed by Neriglisaros [Neriglissar], his sister’s husband. He was king for two years. After Eveilmaradouchos had been killed, Neriglisaros, the man who had plotted against him, succeeded to the throne and was king for four years.”2

Given Nebuchadnezzar’s fatal illness, Evil-Merodach likley ruled as co-regent for a period of time before his father died. Indeed, a cuneiform text seems to indicate that the fourth and fifth months of the accession year of Evil-Merodach overlapped with the final year of his father’s reign.3

Evil-Merodach’s Inscriptions

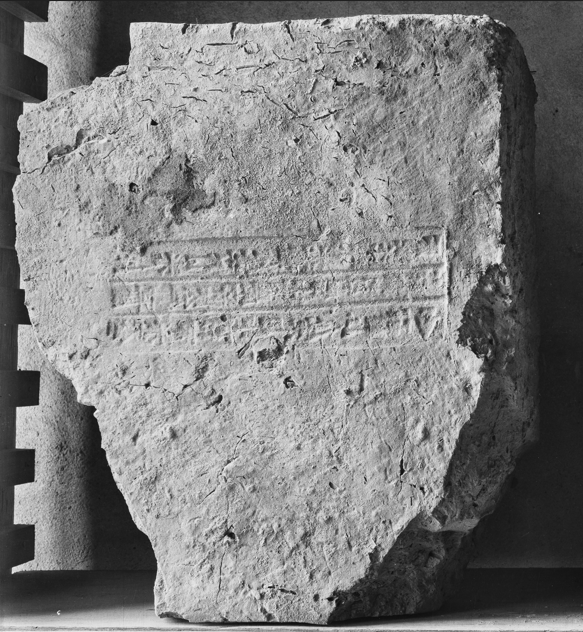

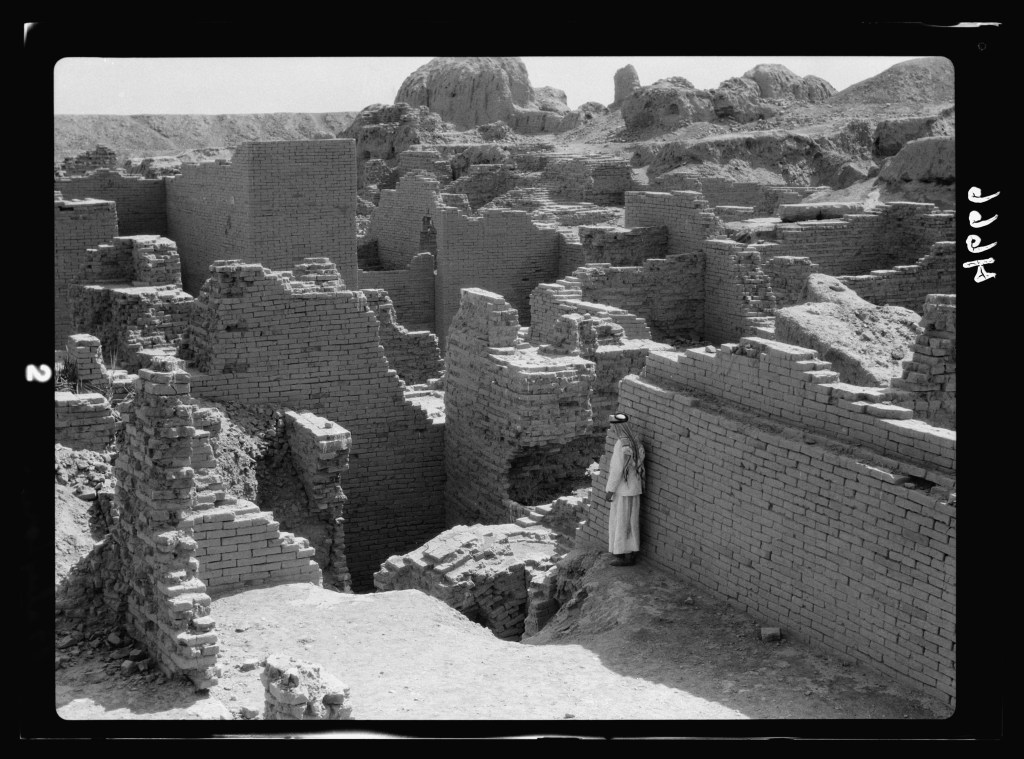

Few inscriptions from Evil-Merodach’s reign remain, possibly due to the short length of his reign. During Robert Koldewey’s excavations at Babylon, his team unearthed two bricks with short, three-line inscriptions of Evil-Merodach on them. They read, “Amēl-Marduk, king of Babylon, the one who renovates Esagil and Ezida, son of Nebuchadnezzar (II), king of Babylon.”4 This may indicate that Evil-Merodach renovated these two important Babylonian temples: Marduk’s temple Esagil (“House whose Top Is High”) at Babylon and Nabû’s temple Ezida (“True House”) at Borsippa. Alternatively, this may have simply been an honorary epithet, as both Nebuchadnezzar and Nabonidus use a similar title.5 Koldewey’s excavations at Babylon also discovered a paving stone with a short inscription reading, “Palace of Amēl-Marduk, king of Bab[ylon], heir of Nebuchadnezzar (II), king of Bab[ylon].”6

Evil-Merodach and Jehoiachin

The only known political act of Evil-Merodach is the one recorded in the Bible.7 Both 2 Kings 25:27–30 and Jeremiah 52:31–34 record that, in the first year of his reign, Evil-Merodach released the Jehoiachin from prison and that the king of Judah was permitted to eat regularly at the king of Babylon’s table for the rest of his life. The obvious question is, “Why would the king of Babylon release the Judahite king who had been taken into exile and honor him?” Two plausible explanations have been given, both based upon interpretations of Babylonian inscriptions.

A cuneiform prism of king Nebuchadnezzar lists prominent officials in his court. Included in that list are three interesting people: Hanunu, chief of the royal merchants, MuSallim-Marduk, an overseer of the slave girls, and Ardi-Nabu, secretary of the crown prince (who was likely Amel-Marduk). William Shea has presented linguistic evidence linking these three court officials with Daniel’s three friends: Hanunu with Hananiah, Misheal with Musallim (Marduk), and Azariah, who was given the name Abed-Nego, with Ardi-Nabu. Of the latter, Shea writes, “ It has long been noted and well-nigh universally accepted in the commentaries that the name Abed-Nego in Dan. 3 is transparently a corruption of Abed-Nebo/Abed-Nabu, ‘servant of Nabu’… Apparently it was distasteful to the biblical writer to have a faithful and proper servant of Yahweh named after a Babylonian god, so the name of that god was intentionally altered.”8 He goes on to note that Abed, which means “servant” in Hebrew and Aramaic, is equivalent to Ardu/Ardi in the language used by the Neo-Babylonians. Thus, Abed-Nabu and Ardi-Nabu mean the same: “Servant of Nabu.” If Ardi-Nabu, the secretary of the crown prince (ie. Amel-Marduk) and Azariah/Abed-Nego of the book of Daniel are the same person, it raises some interesting implications regarding a possible motivation for the release of Jehoiachin. Shea summarizes: “The influence which that secretary may have exercised upon the crown prince could explain his favorable attitude toward Jehoiachin when he became king.”9

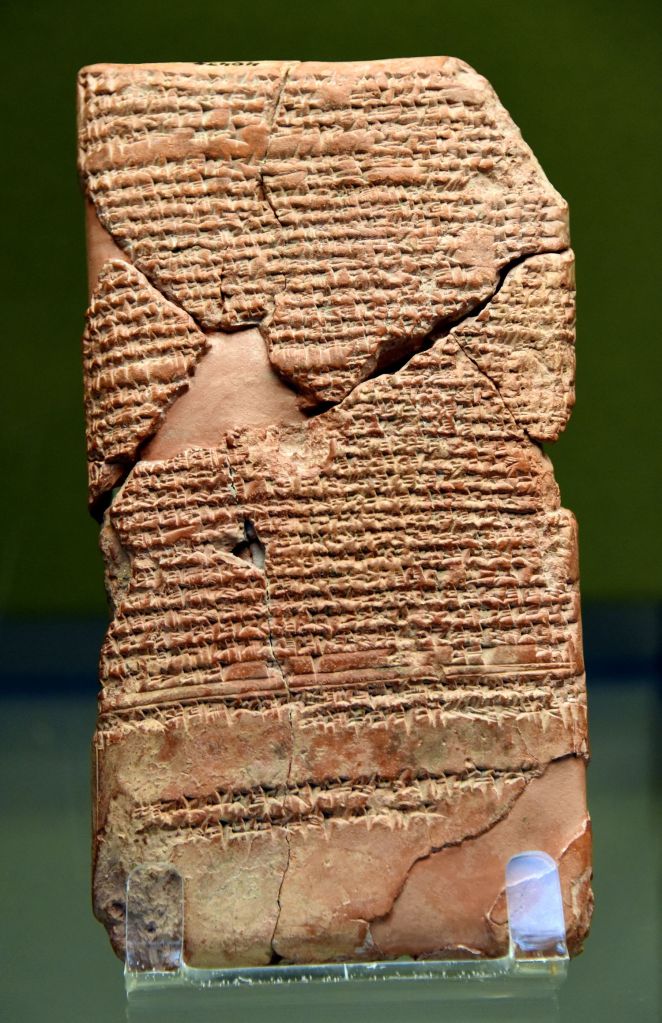

Alternatively, a cuneiform tablet called the “Lament of Nabû-šuma-ukîn” contains the prayer of one of Nebuchadnezzar’s sons who ends up in prison because of a conspiracy against him. In the lament, he proclaims his innocence and prays to Marduk for deliverance. Irving Finkel has proposed that Nabû-šuma-ukîn is biblical Evil-Merodach, who changed his name to Amel-Marduk (lit. “man of Marduk”) after he was released from prison to honor the god he credited with his deliverance.10 If this is the case, Evil-Merodach may have befriended Jehoiachin while they were both in prison, which could explain his benevolence towards the Judahite king once he had ascended the Babylonian throne.

Conclusion

Evil-Merodach’s two-year reign stands in sharp contrast to the 43-year reign of his father, King Nebuchadnezzar. It appears that he was disliked and remembered more for his incompetence than for the greatness his father projected, although a lack of Babylonian texts makes this conclusion tentative at best. Despite the fact that little is known about Evil-Merodach’s reign, there are a number of interesting possible connections between cuneiform texts and the Biblical record.

Cover Photo: © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft; Foto: Robert Koldewey, 1911 (Bab Ph 2302). Used with Permission.

Endnotes:

1 Jona Lendering, “Uruk Kings List.” Livius.org. Online: https://www.livius.org/sources/content/uruk-king-list/ (Accessed Jan. 10, 2024).

2 Stanley Mayer Burstein. The Babyloniaca of Berosus. (Malibu: Undena Publications, 1978), p. 28.

3 R. H. Sack, Amel-Marduk: 562–560 B.C., Alter Orient und Altes Testament 4 (Neukirchen-Vluyn, 1972), 3

4 Frauke Weiershäuser and Jamie Novotny, eds. The Royal Inscriptions of Amēl-Marduk (561-560 BC), Neriglissar (559-556 BC), and Nabonidus (555-539 BC), Kings of Babylon. (University Park: Eisenbrauns, 2020), p. 30

5 Weiershäuser and Novotny, 29.

6 Weiershäuser and Novotny, 31.

7 Weiershäuser and Novotny, 1.

8 William H. Shea, “Daniel 3: Extra-Biblical Texts and the Convocation on the Plain of Dura.” Andrews University Seminary Studies, Spring 1982, Voi. 20, No. 1, 48-49.

9 Shea, 49.

10 Edition: I. Finkel, “The Lament of Nabû-šuma-ukîn”, in J. Renger (ed.), Babylon: Focus mesopotamischer Geschichte, Wiege früher Gelehrsamkeit, Mythos in der Moderne, CDOG 2, Saarbrücken, 1999, pp. 333-338.