In the days of Eliashib, Joiada, Johanan, and Jaddua, the Levites were recorded as heads of fathers’ houses; so too were the priests in the reign of Darius the Persian (Neh 12:22 ESV).

There are five Persian kings specifically named in the Bible: Cyrus (2 Chr 36:22-23), Darius I (Ezra 4:5), Xerxes/Ahasuerus (Esther 1:1-3), Artaxerxes I (Ezra 7:1-22), and “Darius the Persian,” (Neh. 12:22). Having written archaeological biographies on the first four Persian kings, it is time to determine who Darius the Persian is, and learn about his reign.

The Identity Darius the Persian

Identifying Darius the Persian requires a comparison of the reigns of the Persian kings named Darius and the dates of the high priests listed in Nehemiah 12:22–23.1

Three Persian kings bore the name Darius: Darius I, also known as Darius the Great (522–486 BC); Darius II (423–404 BC), who was known to the Greeks as Nothus (lit. bastard, referring to his illegitimate birth); and Darius III (335–330 BC), also known as Codomannus (warlike).2

The four high priests named in Nehemiah 12:22 are Eliashib, Joiada, Johanan, and Jaddua. While they are not described explicitly as high priests in this passage, the historian Josephus records that each served in that role.3 We can deduce the approximate years they served as High Priests from biblical chronology and archaeological evidence:

- Eliashib – Mentioned as high priest when Nehemiah arrived in Jerusalem to oversee the rebuilding of the walls (Neh. 3:20–21). Since Nehemiah came to Jerusalem in the twentieth year of Artaxerxes I (Neh. 1:1; 2:1), Eliashib was serving as high priest in 445 BC.4

- Joiada – Little is known about him, but Nehemiah 13:28 records that “the son of Eliashib the high priest, was the son-in-law of Sanballat the Horonite. Therefore I chased him from me.” This occurred sometime after 433 BC, since in the 32nd year of Artaxerxes I, Nehemiah was recalled to the Persian king and only returned to Jerusalem after some time (Neh. 13:6).

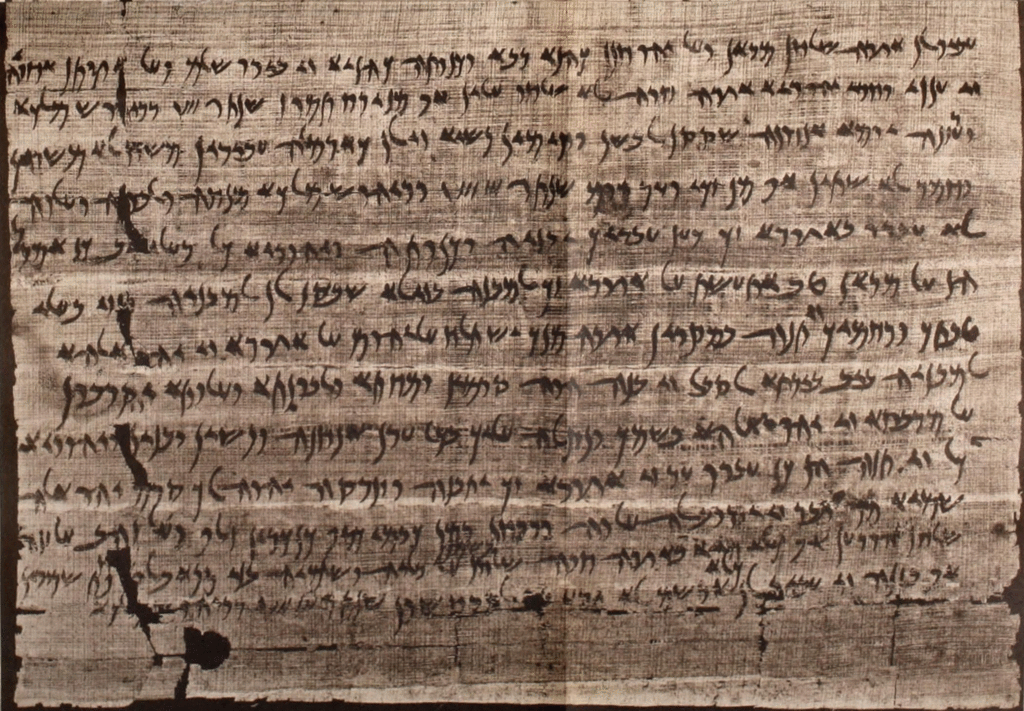

- Johanan – Named in Elephantine Papyrus No. 30, which is specifically dated to the “20th of Marheshwan the 17th year of Darius the king” (line 30).5 James C. Vanderkam notes that “factors of history and script indicate that the Darius in question is Darius II Nothus…The twentieth day of the eighth month (= Marheshwan) of his seventeenth year would be November 26, 407.”6

- Jaddua – Named by Josephus as a contemporary of Alexander the Great, who ruled from 336–323 and of Darius III.7

Nehemiah 12:23 adds further chronological information, noting: “As for the sons of Levi, their heads of fathers’ houses were written in the Book of the Chronicles until the days of Johanan the son of Eliashib.” While Jaddua is mentioned in verse 22, he is not named in verse 23. This is significant, as verse 23 states that the register of Levites was kept only up to the time of Johanan, which is linked contextually to the reign of Darius the Persian mentioned at the end of verse 22.

Since the reign of Darius the Persian appears to be linked to the high priesthood of Johanan—and because Johanan is specifically named in the Elephantine papyri as serving during the reign of Darius II—it seems most likely that Darius the Persian refers to Darius II. Persian historian Edwin Yamauchi also concludes that Darius the Persian was probably Darius II.8

The Reign of Darius II

Darius II was the son of Artaxerxes I, although he was not the crown prince. When Artaxerxes I died, he had only one legitimate son, who took the throne name Xerxes II and became king.9 According to the ancient Greek historian Ctesias, Xerxes II reigned for only 45 days before he was assassinated by his half-brother Secydianus, who himself reigned for only six months before being overthrown by his half-brother Ochus, who then took the throne as Darius II. Ctesias records:

While Xerxes was in a drunken slumber in the palace at a festival, they entered and killed him, forty-five days after his father’s death….Secyndianus became king…Ochus surrounded himself with a large army and it seemed likely that he would become king. Arbarius, the commander of Secyndianus’ cavalry, defected to Ochus’ side….Ochus became king and was known by a new name, Darius (II)… [Secyndianus] was captured and thrown into the ashes and killed after a reign of six months and fifteen days.10

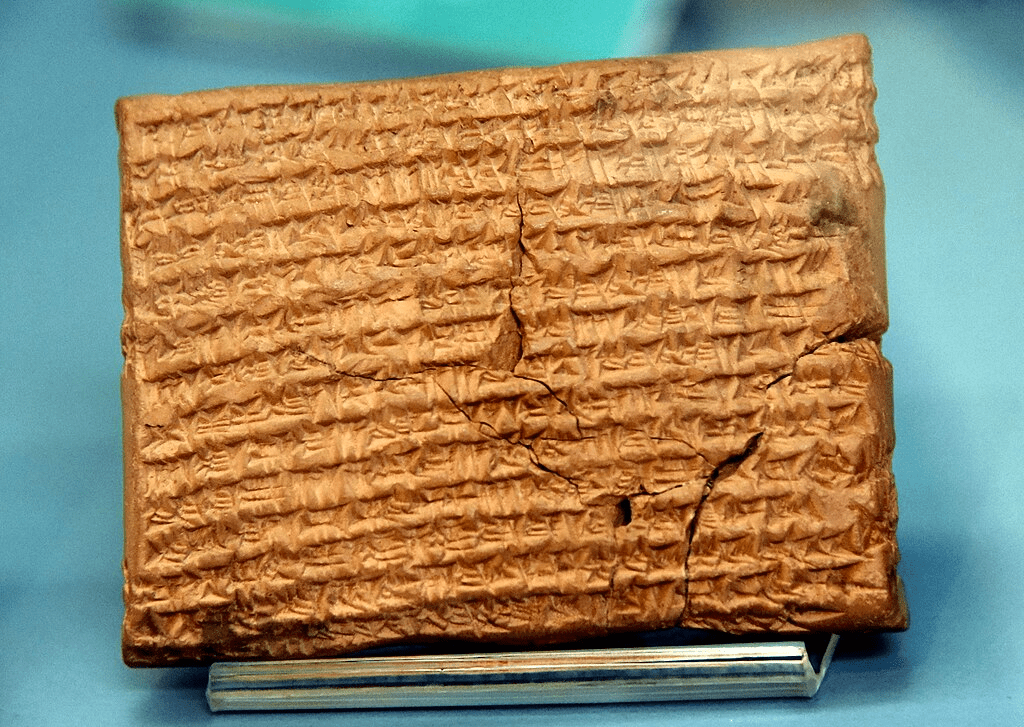

Babylonian tablets from the Murašû Archive provide evidence that the events between the death of Artaxerxes I and the accession of Darius II unfolded between the end of December 424 BC and February 423 BC. Moreover, the reigns of Xerxes II and Sogdianus were not officially recognized by the Babylonian scribes.11

Ochus, now reigning as Darius II, faced numerous revolts of his own, including one by his brother, Arsites.12 He crushed each of these challenges to his rule as they arose.

Darius II became involved in the Peloponnesian War, a political struggle between the Greek city-states of Athens and Sparta, when the Athenians provoked him by supporting a rebellion in Persia led by Amorges. Darius authorized his satraps in the region to fund Sparta’s war effort against Athens. According to Pierre Briant, “This mission involved launching overt operations against Athens so as to reaffirm Achaemenid dominion over the Asia Minor coast.”13 Darius II signed three treaties with Sparta, each of which was recorded by the Greek historian Thucydides (ca. 460–395 BC) in his History of the Peloponnesian War.14

Darius II maintained Persian control over Egypt throughout his reign. This is attested by Aramaic documents that mention Persian officials in Egypt, a cartouche of Darius II in the temple of El-Kharga, and a seal from Memphis inscribed with the name of Darius II, depicting a royal hero triumphing over two sphinxes.15

Persia also retained control over Jerusalem and the province of Yehud (Judah) in the satrapy of “Beyond-the-River.” While few surviving documents shed light on this period, one Persian governor of Judah is known from the reign of Darius II: Bagohi (Bagoas), who is called the “governor of Judah” in the Elephantine papyri.16

The Coins of Darius II

The standard coins of the Persian Empire were gold darics and silver sigloi, both of which were minted during the reign of Darius II. Throughout the fifth century, including during Darius II’s reign, coins were also minted in Philistia, operating under Persian authority. Some of these coins have been found in excavations throughout Israel.17 It was not until the fourth century, after the reign of Darius II, that coins began to be minted in Judah bearing the inscription “Yehud,” the name of the province.18

The Inscriptions of Darius II

Few royal inscriptions from Darius II have survived. One from Susa (D2Sb), discovered on two column bases reads,

I am Darius, the great king, the king of kings, the king of all nations, the king of this world, the son of King Artaxerxes, the Achaemenid. King Darius says: My father Artaxerxes had almost built this palace. Later, by the grace of Ahuramazda, I have built this palace.19

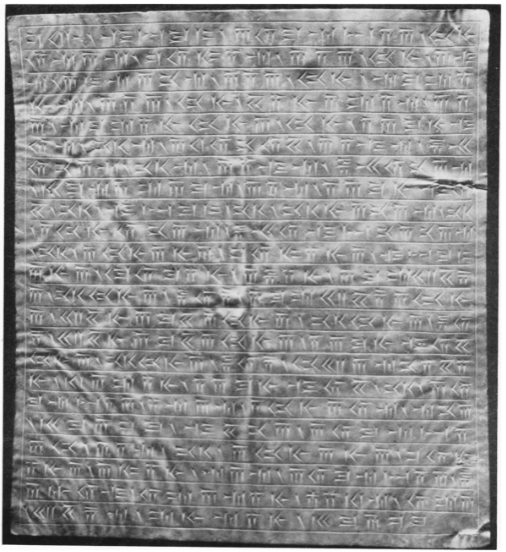

The longest inscription (D2Ha), reported to have been discovered at Hamada (ancient Ecbatana), is recorded on a gold tablet and reads, in part,

“I am Darius the great king, king of kings, king of countries having many kinds of men, king in this great earth far and wide, son of Artaxerxes the king, of Artaxerxes (who was) son of Xerxes the king, of Xerxes (who was) son of Darius the king, an Achaemenian. Saith Darius the king: Ahuramazda bestowed this land on me. I am king in this land–may Ahuramazda protect my royal house and the kingship which he bestowed upon me.”20

Darius II is also named on several column base inscriptions from his son, Artaxerxes II.

The Death of Darius II

Darius died in 404 BC, after reigning for 19 years, and was succeeded by his son, Artaxerxes II. He is believed to have been buried in the left-most tomb in the cliff-side necropolis at Naqsh-e Rustam.

Conclusion

Darius II is most likely the same as Darius the Persian, named in Nehemiah 12:22, during whose reign the names of the priests were recorded in Jerusalem. He ruled for 19 years, continuing Persia’s control over the province of Yehud (Judah) in the satrapy of “Beyond-the-River.” During this time, the Temple in Jerusalem continued to operate as the center of Jewish worship, and the priests held significant influence in the daily life of the people. However, the local governors were ultimately under Persian authority

Cover Photo: A depiction of Darius II from his tomb in Naqsh-e Rustam. Credit: Diego Delso / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 4.0

Endnotes

1 I am indebted to scholar Lawrence Mykytiuk for sharing with me his research into this issue and his reasons for identifying Darius the Persian as Darius II Nothus.

2 Ewin M. Yamauchi, Persia and the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1990), p. 129.

3 Josephus, Antiquities, 11.7.1–2.

4 James C. Vanderkam, From Joshua to Caiaphas: High Priests after the Exile (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2004), p. 50.

5 A.E. Cowley, Aramaic Papyri of the Fifth Century (Oxford: Clarendon, 1923), p. 108–119.

6 James C. Vanderkam, From Joshua to Caiaphas: High Priests after the Exile (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2004), p. 55.

7 Josephus, Antiquities, 11.8.2–5.

8 Ewin M. Yamauchi, Persia and the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1990), p. 130.

9 Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Translated by Peter T. Daniels. (University Park: Eisenbrauns, 2002), p. 772.

10 Ctesias §48–50, Lloyd. Llewellyn-Jones and James. Robson. Ctesias’ History of Persia: Tales of the Orient (New York: Routledge, 2010), p. 192–193.

11 Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Translated by Peter T. Daniels. (University Park: Eisenbrauns, 2002), p. 588.

12 Heleen Sanchisi-Weerdenburg, “DARIUS iv. Darius II,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, VII/1, p. 50-51. Online: http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/darius-iv (Accessed June 21, 2025).

13 Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Translated by Peter T. Daniels. (University Park: Eisenbrauns, 2002), p. 592.

14 “The treaties between Persia and Sparta,” Livius.org. Online: https://www.livius.org/sources/content/thucydides-historian/the-treaties-between-persia-and-sparta/ (Accessed June 24, 2025).

15 Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Translated by Peter T. Daniels. (University Park: Eisenbrauns, 2002), p. 602.

16 Nahman Avigad, “Bullae and Seals from a Post-Exilic Judean Archive.” Qedem, Vol. 4, 1976, p. 35. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43575944 (Accessed June 21, 2025).

17 Haim Gitler and Oren Tal, “The Silver Coinage of Philistia in the Fifth and Fourth Centuries BCE,” Israel Numismatic Research 5 (2010): 59–87.

18 Haim Gitler and Catherine Lorber, “A New ‘Yehud’ Coin of Hezekiah,” Israel Numismatic Journal 17 (2011): 74–76.

19 “D2Sb,” Livius.org. Online: https://www.livius.org/sources/content/achaemenid-royal-inscriptions/d2sb/ (Accessed June 21, 2025).

20 Herbert H. Paper. “An Old Persian Text of Darius II (D2Ha).” Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 72, no. 4, 1952, pp. 169–70. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/596379, (Accessed June 21, 2025).