Setting the Stage

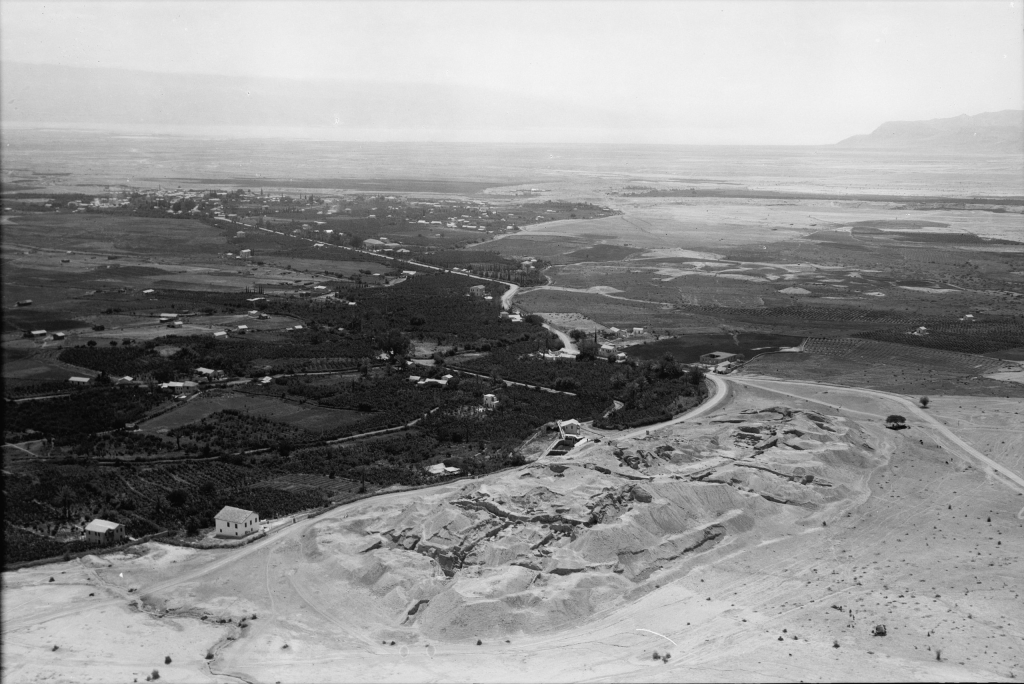

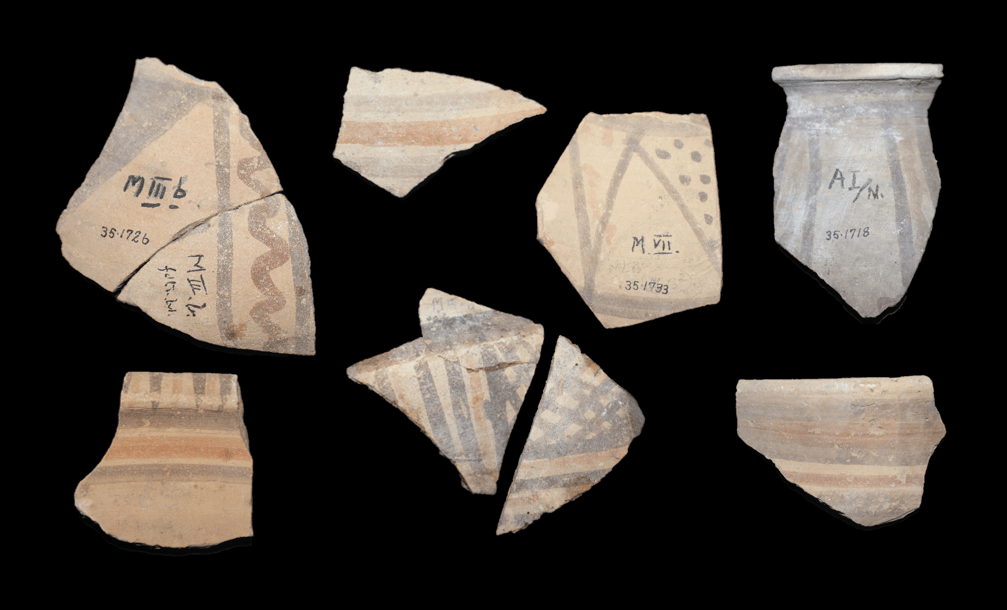

For the past several years, I have conducted a deep dive into the latest archaeological research on Jericho as part of my master’s thesis. This involved hundreds of hours of investigation, two trips to Tell es-Sultan (ancient Jericho), studying Late Bronze (LB) pottery from Jericho in person at the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem and the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. Along the way, I consulted the world’s leading expert in LB ceramic typology.1

To organize my research, I built a database of all known published LB artifacts from Jericho, as well as those held in museums around the world. In total, my database currently contains 572 LB artifacts, including 174 vessels, 392 sherds, four scarabs, one cuneiform tablet, and one figurine.

All of this came together in my thesis entitled “Tell es-Sultan/Jericho City V: The City the Israelites Conquered?” which was recently published as a book through Trowel Press entitled Joshua’s Jericho: The Latest Archaeological Evidence for the Conquest. It is available through Amazon here: https://a.co/d/iCUWXQW

Over the next few months, I will be releasing some of my research about the fall of Jericho, as described in Joshua 6. In this first post, I will set the stage by describing the history of excavations at Jericho, the debate surrounding the dating of City IV, as well as present my view that City V is the city that Joshua conquered.

The Importance of Jericho

Jericho poses a problem to those, like me, who uphold the historical reliability of the Bible. The results of multiple excavations at the site have been both contradictory and confusing. Many scholars believe the archaeological data are at odds with the description of the fall of Jericho in Joshua 6. For example, Finkelstein and Silberman noted that “the famous scene of the Israelite forces marching around the walled town with the Ark of the Covenant, causing Jericho’s mighty walls to collapse by the blowing of their war trumpets was, to put it simply, a romantic mirage.”2

Yet, if the account of the fall of Jericho in the book of Joshua is a historical record of an actual event, one would expect to find some evidence of occupation, fortification, and destruction around the time of Joshua. I believe that the most recent excavations at Jericho by Lorenzo Nigro and his team from Sapienza University, combined with past excavations, provide such evidence.

Which City is Joshua’s Jericho?

Tell es-Sultan consists of a series of cities, built on top of one another throughout the millennia, creating strata, much like a layered chocolate cake. The controversy surrounding the stratum at Jericho associated with Joshua’s conquest has largely centered on the dating of the well-known destruction of City IV. While everyone agrees that this Canaanite city of Jericho was destroyed in a violent, fiery manner, not everyone agrees on the date for this event.

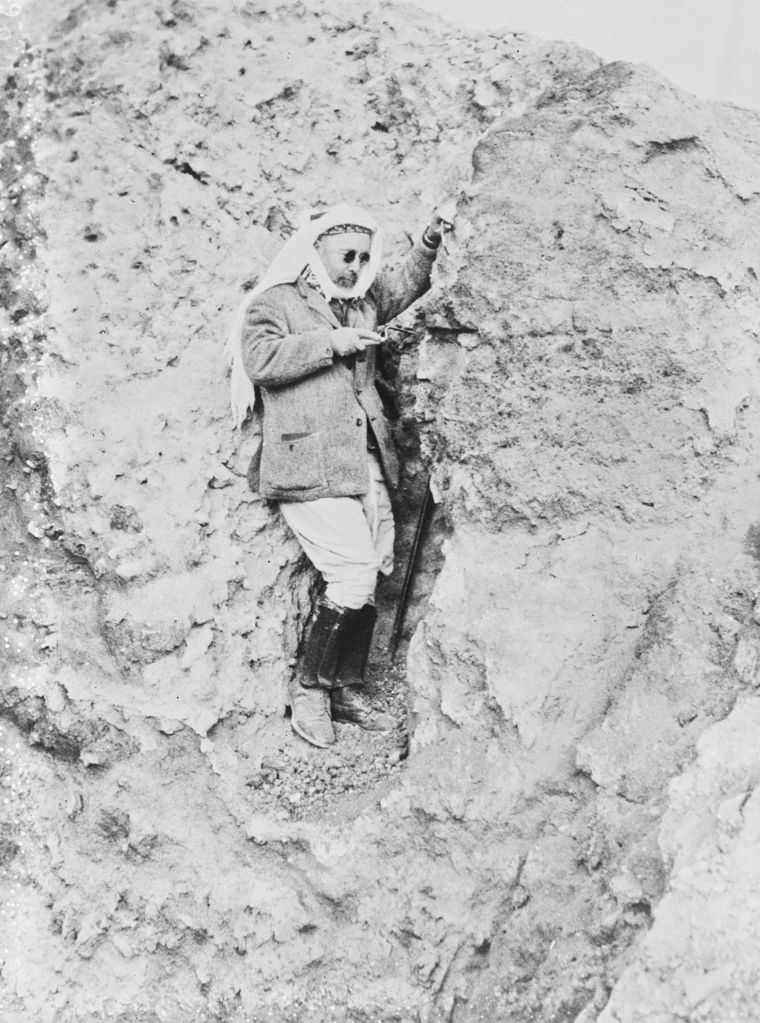

The first excavators, Sellin and Watzinger, who dug seasonally from 1907 to 1909 and again in 1911, originally misidentified the stone Cyclopean Wall as Israelite and the double mudbrick city wall as the Canaanite walls that came tumbling down before Joshua’s army.3 Later, in 1926, Watzinger adjusted his conclusions in light of other excavations, attributing the Cyclopean Wall to the last phase of the Middle Bronze Age and the double mudbrick wall to the end of the Early Bronze Age.4 This essentially placed the destruction of City IV in the Middle Bronze Age, much too early to have been destroyed by Joshua, who conquered the city in the Late Bronze Age.5

In the 1930s, archaeologist John Garstang excavated a residential area of Jericho and concluded that the fiery destruction of the city occurred in the Late Bronze Age, ca. 1400–1385 BC, linking it with Joshua and the Israelites.6

From 1952–58, Kathleen Kenyon excavated at Jericho and corrected Garstang’s view, dating the destruction of City IV to the end of the Middle Bronze Age, ca. 1550 BC.7

In the early 1990s, Bryant Wood, who did not excavate at Jericho, suggested that Kenyon’s analysis of the date of this destruction was incorrect, as he believed she had based her conclusions largely on the absence of Cypriot bichrome pottery.8

Most recently, Lorenzo Nigro, who excavated from 1997 to 2000 and 2009 to 2023, upheld Kenyon’s dating of the destruction of City IV to the end of the Middle Bronze Age.9 Moreover, one of the major achievements of Nigro’s team from Sapienza University was a harmonization of the data from previous excavations with their own into an overall periodization of the site.10 According to their stratigraphy, City V occupied the site during the LB I and II periods.11 Indeed, they found LB remains on the southern, eastern, and north-western edges of the tell.12

| The Stratigraphy of Jericho According to Lorenzo Nigro’s Team from Sapienza University (Adapted from Nigro, Lorenzo. 2016. “TELL ES-SULTAN 2015: A Pilot Project for Archaeology in Palestine.” Near Eastern Archaeology 79.1: 4–17 and Nigro, Lorenzo and Jehad Yasine. 2024. “Interim Report on the Excavations at Tell es-Sultan, Ancient Jericho (2019-2023): The Bronze and Iron Age Cities.” Vicino Oriente XXIX, 47-96.) | ||

| ARCHAEOLOGICAL PERIOD | DATES | STRATUM/CITY |

| Epipaleolithic (Late Natufian) | 10500–8800 BC | Sultan Ia |

| Pre-Pottery Neolithic A | 8800–7500 BC | Sultan Ib |

| Pre-Pottery Neolithic B | 7500–6000 BC | Sultan Ic |

| Pottery Neolithic A | 6000–5300 BC | Sultan IIa |

| Pottery Neolithic B | 5300–4300 BC | Sultan IIb |

| Chalcolithic | 4300–3500 BC | Sultan IIc |

| Early Bronze Age IA | 3500–3300 BC | Sultan IIIa1 |

| Early Bronze Age IB | 3300–3050 BC | Sultan IIIa2 |

| Early Bronze Age IIA | 3050–2850 BC | Sultan IIIb1 |

| Early Bronze Age IIB | 2850–2700 BC | Sultan IIIb2 |

| Early Bronze Age IIIA | 2700–2500 BC | Sultan IIIc1 |

| Early Bronze Age IIIB | 2500–2300 BC | Sultan IIIc2 |

| Early Bronze Age IVA | 2300–2200 BC | Sultan IIId1 |

| Early Bronze Age IVB | 2200–2000 BC | Sultan IIId2 |

| Middle Bronze Age IA | 2000–1900 BC | Sultan IVa1 |

| Middle Bronze Age IB | 1900–1800 BC | Sultan IVa2 |

| Middle Bronze Age IIA | 1800–1700 BC | Sultan IVb1 |

| Middle Bronze Age IIB | 1700–1650 BC | Sultan IVb2 |

| Middle Bronze Age III | 1650–1550 BC | Sultan IVc |

| Late Bronze Age IA | 1550–1470 BC | Sultan Va |

| Late Bronze Age IB | 1470–1400 B.C.E | |

| Late Bronze Age IIA | 1400–1300 BC | Sultan Vb |

| Late Bronze Age IIB | 1300–1200 BC | |

| Iron Age IA | 1200–1136 BC | Sultan VIa |

| Iron Age IB | 1136–960 BC | |

| Iron Age IIA | 960–840 BC | Sultan VIb |

| Iron Age IIB | 840–732 BC | |

| Iron Age IIC | 732–585 BC | Sultan VIc |

| Persian Period | 535–333 BC | Sultan VIIa |

| Hellenistic Period | 332–64 BC | Sultan VIIb |

| Roman Period | 64 BC–AD 324 | Sultan VIII |

| Byzantine Period | 324–636 | Sultan IX |

| Early Islamic Period | 636–1000 | Sultan X |

| Crusader Period & Middle Islamic | 1000–1250 | |

| Late Islamic (Mamluk) Period | 1250–1516 | |

| Ottoman Period | 1516–1918 | Sultan XI |

| After World War I | 1919–Today | Sultan XII |

My View

If Watzinger, Kenyon, and Nigro are correct, City IV could not have been the city that Joshua and the Israelites conquered, as it was destroyed much too early. However, according to the latest stratigraphy, City V was occupied in the Late Bronze Age, suggesting it may be the city that fell during the conquest.

When I began my research, I realized that few evangelical Christian scholars had interacted in a meaningful way with Nigro’s research. In fairness, it has only been in the last few years that he has published anything of substance about Jericho in the Late Bronze Age.13 Thus, in addition to rereading the writings of Sellin & Watzinger, Garstang, Riklan,14 and Kenyon, I have read everything I could find that Nigro has written about Jericho City V.

While he has not yet15 published a final excavation report, I believe there is enough detail in his current publications to establish that Jericho was occupied, fortified, and destroyed around the time the bible indicates the conquest occurred. In the coming months, I will be sharing some of my research to support the claim that City V is a viable candidate for the city that Joshua conquered.

Acknowledgements

Some of my readers who know my role as a Staff Researcher and Writer with the Associates for Biblical Research (ABR) may be surprised to find that I hold a different view on the city Joshua conquered than Dr. Bryant Wood, ABR’s Director of Research. He believes that City IV was the city that Joshua conquered, siding with Garstang over Kenyon16 (and presumably Nigro). I am grateful for Dr. Wood’s research and have tried to build upon his work. Much of the latest archaeological data, including refinements in comparative ceramic typology, was not available to him when he developed his position over three decades ago. While we have reached different conclusions about which city (stratum) at Jericho was conquered by the Israelites, I have a great respect for Dr. Wood and his legacy.

I am also grateful for the support of those at ABR who encouraged me to pursue my research, even though it went in a different direction than we, as an organization, had been presenting for many years. One of the things I appreciate about ABR is that they allow scholars to hold different views, as long as they hold to the supremacy of the Bible. Scott Lanser, the former president, as well as Henry Smith, Scott Stripling, and Gary Byers, were willing sounding boards, helping me clarify and condense my research. Both Scott and Gary were advisors on my thesis committee.

As I seek to change the paradigm by demonstrating that the archaeological evidence from City V aligns with the biblical criteria for the occupation, fortification, and destruction of the city, I am thankful for those who have helped guide me in my research.

Next Month: In part two of this series, I will be presenting my approach to the date of the fall of Jericho. If one looks in the wrong time period, then the evidence for the conquest will be missed.

Cover Photo: Bill Schlegel / BiblePlaces.com / Used with Permission

Endnotes

1 Dr. Robert Mullins was gracious enough to interact with me regarding the bichrome pottery discovered at Jericho. He co-wrote the chapter on Late Bronze Age pottery in the key book on ceramic typology that we use on our dig in Israel. Mullins, Robert A. and Eli Yannai. 2019. “Late Bronze Age I–II,” in The Ancient Pottery of Israel and its Neighbors, Volume 3: From the Middle Bronze Age through the Late Bronze Age, ed. Seymour Gitin. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

2 Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman. The Bible Unearthed. New York: The Free Press, 2001), 82.

3 Lorenzo Nigro, “In the Shadow of the Bible. Archaeological Investigations by the Deutsches Palästina Vereins before the First World War: Taannek, Megiddo, Jericho, Shechem.” In Archéologie dans l’Empire Ottoman Autour de 1900: Entre Politique, Économie et Science, edited by V. Krings and I. Tassignon, (Bruxelles-Rome: Institut Historique Belge de Rome, 2004), 224–225.

4 Maura Sala, “The Archaeological Expeditions to Tell es-Sultan (1868-2012).” In Archaeology in the ‘Land of Tells and Ruins’: A History of Excavations in the Holy Land Inspired by the Photographs and Accounts of Leo Boer. Ed. Bart Wagemakers. (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2014), 124.

5 I will address the date of the conquest in my next blog. According to a literal reading of the data in 1 Kings 6:1, the fall of Jericho occurred around 1406 BC. However, the biblical text has some uncertainty about the exact year of Solomon’s fourth regnal year, so there’s a degree of imprecision built in. To complicate matters further, the Septuagint (the ancient Greek translation of the Old Testament) reads “440th year” instead of “480th year,” which shifts the conquest date to about 1366 BC. In my own work, I prefer to use what I call a “chronological window” approach, which looks for archaeological evidence that is ± 20 years on either side of both possible “biblical dates.”

6 John Garstang and J.E.B. Garstang. The Story of Jericho. (London: Marshall, Morgan & Scott, Ltd., 1948), 179.

7 Kathleen M. Kenyon, “Some Notes on the History of Jericho in the Second Millennium B.C.” Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 83:2, (1951), 117.

8 Bryant G. Wood, “Did the Israelites Conquer Jericho? A New Look at the Archaeological Evidence.” Biblical Archaeology Review 16.2 (March/April 1990), 50.

9 Lorenzo Nigro, “TELL ES-SULTAN 2015: A Pilot Project for Archaeology in Palestine.” Near Eastern Archaeology, 79.1 (2016),11–15.

10 Lorenzo Nigro, “The Italian-Palestinian Expedition to Tell es-Sultan, Ancient Jericho (1997–2015): Archaeology and Valorisation of Material and Immaterial Heritage,” In Digging Up Jericho: Past, Present and Future, eds. Rachael Thyrza Sparks, Bill Finlayson, Bart Wagemakers and Josef Mario Briffa, (Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd., 2020), 178.

11 Lorenzo Nigro, “TELL ES-SULTAN 2015: A Pilot Project for Archaeology in Palestine.” Near Eastern Archaeology, 79.1 (2016),11.

12 Lorenzo Nigro, “The Italian-Palestinian Expedition to Tell es-Sultan, Ancient Jericho (1997–2015): Archaeology and Valorisation of Material and Immaterial Heritage,” In Digging Up Jericho: Past, Present and Future, eds. Rachael Thyrza Sparks, Bill Finlayson, Bart Wagemakers and Josef Mario Briffa, (Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd., 2020), 204.

13 Lorenzo Nigro, “Tell es-Sultan/Jericho in the Late Bronze Age,” in Durch di Zeiten: Through the Ages, eds. Katja Soennecken, Patrick Leiverkus, Jennifer Zimni and Katharina Schmidt. (Munich: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 2023), 599–614.

14 In December 1992, Shimon Riklin, on behalf of the Staff Officer for Judea and Samaria, conducted a sounding on the west side of the tell, to the south of Kenyon’s Trench I and unearthed a section of the EB mudbrick city wall. His work has no bearing on the date of City IV, but, for completeness, I read his excavation report, which is often overlooked.

15 As of September 2025

16 Bryant G. Wood, “Did the Israelites Conquer Jericho? A New Look at the Archaeological Evidence.” Biblical Archaeology Review 16.2 (March/April 1990), 44–57.

Thank you, Bryan. I look forward to reading Part 2.

Since my own research leads me to different conclusions, based on an alternative biblical chronology derived primarily from the Septuagint (especially the Lucianic tradition) and a revised Egyptian timeline, I sometimes find this Jericho debate both fascinating and a bit frustrating! It seems much of the debate could be resolved—or at least reframed—by seriously considering alternative models.

I believe the late Christine Tetley’s work (in both of her books) deserves renewed attention. While I don’t agree with her on every detail, I think she was generally on the right track, and her research offers a valuable launching point—though, admittedly, I’ve made my own revisions to her chronology.

Tetley’s conclusions would relocate the 18th Dynasty of Egypt approximately 100 years earlier than is currently accepted, which at first glance might seem implausible. However, if we utilize the LXX-based numbers, interpret 1 Kings 6:1 as referencing a cumulative total of non-sequential years (439), and count a 215-year sojourn, then the Exodus would be closer to 1547 BC, not 1446 BC.

That, in turn, would place the destruction of Jericho at around 1507 BC—remarkably close to the accepted destruction layer of City IV. Under this scenario, Amenhotep II could still function as the Pharaoh of the Exodus, and the presence of a scarab from Amenhotep III at Jericho aligns perfectly: he would have been mid-reign during the conquest, making this a synchronism rather than an anomaly – a feature, not a bug (pun intended ;>).

With all due respect, I suggest that reconsidering reliance on the 1446 BC Exodus date, the Masoretic-based Thiele chronology, and conventional Egyptian dating might open up new possibilities for synchronizing the biblical and archaeological records—possibilities that are obscured by current assumptions. These longstanding frameworks may be preventing us from seeing the synchronisms that the evidence readily supports.

If my persistence on these points sometimes comes across as repetitive, I apologize. Like you, I am passionate about pursuing the truth. Hopefully, you will be patient with my respectful disagreement, even as ABR has been graciousness in supporting your own differing views.