At that time Merodach-Baladan son of Baladan king of Babylon sent Hezekiah letters and a gift, because he had heard of Hezekiah’s illness (2Kgs 20:12).

Merodach-Baladan II lived in the eighth century BC and was a contemporary of King Hezekiah. They shared a common foe in the Assyrian, which may have been the true reason Merodach-Baladan reached out to the Judahite king. Like Hezekiah, he resisted Assyrian domination and fought for independence.

Merodach-Baladan’s Akkadian name was Marduk-apla-iddina (lit. “Marduk has given me an heir”). He reigned as king of Babylon from ca. 721–710 BC, before being chased into exile by Sargon II of Assyria. He later regained the throne for six to nine months in 703 BC after Sennacherib came to power, but he was again defeated and fled into exile.

Merodach-Baladan’s First Reign

Merodach-Baladan initially reigned in Babylon for twelve years. Little is known about his reign in Babylon, aside from his frequent conflicts with the Assyrians. There are only a few royal inscriptions from his time as king of Babylon.

In one inscription Merodach-Baladan claims to have defended Babylon against the Subarians with the help of his god:

A stamped brick from early in his reign indicates he made repairs to Eanna, the temple of Ishtar at Uruk: “For the lady…lady of the lands, his lady, Merodach-Baladan, king of Babylon, offspring of Eriba-Marduk, king of Babylon, Eanna, her beloved temple, built.”2

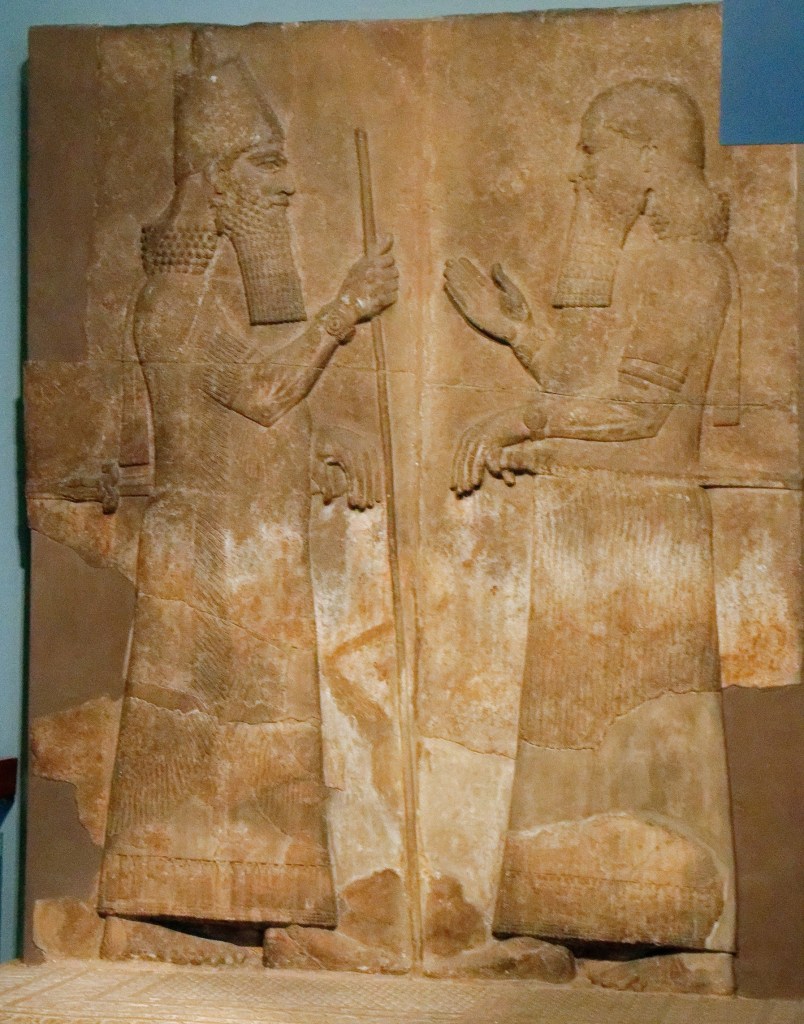

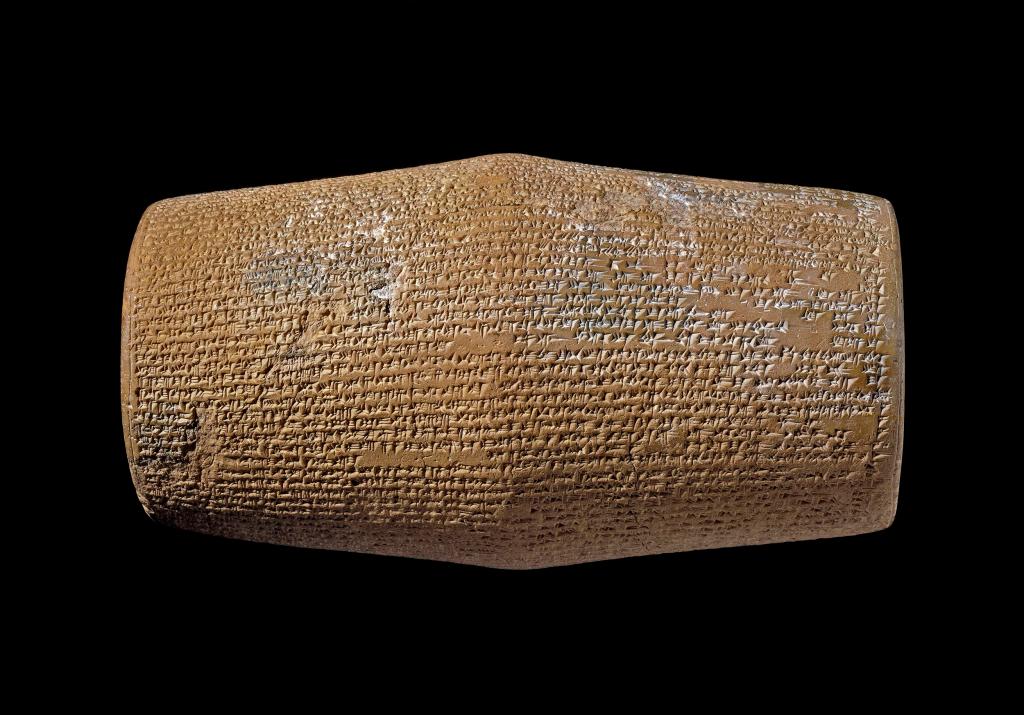

The most famous artifact is a boundary stone that records the king’s grant of land to the governor of Babylon in the seventh year of his reign.3 It contains the only known depiction of Merodach-Baladan; the king (on the left) is suitably larger than the governor of Babylon and is wearing the royal conical hat while dressed in a Babylonian robe.

All throughout his reign, Merodach-Baladan fought against the Assyrians. According to the Babylonian Chronicles, “From the accession ye[ar of] Merodach-baladan (II) until the tenth year [Assyria/Sargon (II)] was belligerent towards Merodach-baladan (II).”4

Eventually, Sargon II was able to defeat the Babylonian king and Merodach-Baladan went into exile in the territory of Elam. The Babylonian Chronicle (ABC 1) records:

The twelfth year of Merodach-baladan (II): Sargon (II) went down [to Akkad] and did battle against [Merodach-bala]dan (II). Merodach-baladan (II) [retreated] before [him] (and) fled to Elam. For twelve years [Merodach-balad]an (II) ruled Babylon.”5

Merodach-Baladan’s Second Reign

When Sargon died, his son, Sennacherib, became king of Assyria. In 703 BC, Merodach-Baladan took advantage of this transition of power to return to Babylon and reclaim the throne. His second reign was short-lived: within a year, Sennacherib had marched on Babylon to overthrow Merodach-Baladan and bring the Babylonians back under Assyrian control.

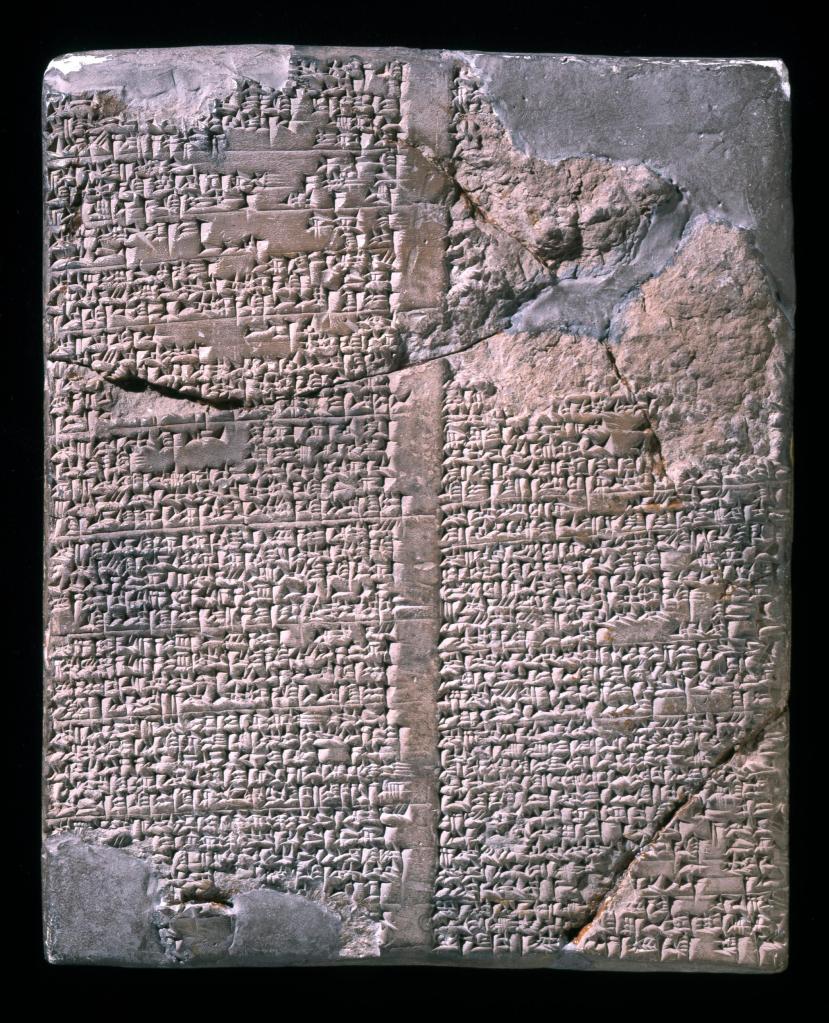

A lengthy inscription on a clay cylinder of Sennacherib describes the coalition Merodach-Baladan assembled to resist Assyria and the battle that ensued.

Sennacherib described Merodach-Baladan as an “evil foe, a rebel with a treacherous mind, and evildoer whose villainous acts are true.” The Babylonian king had assembled a coalition of Elamites, Arameans, and the kings of various city-states to oppose the Assyrians. Sennacherib says he raged like a lion and ordered the Assyrian troops to march on Babylon. In the ensuing battle, the Assyrians defeated the rebel alliance and Merodach-Baladan fled:

With my merciless warriors, I set out for Kish against Marduk-apla-iddina (II) (Merodach-Baladan II). Moreover, he, (that) evildoer, saw the cloud of dust of my expeditionary force from afar and fear fell upon him. He abandoned all of his forces and fled to the land Guzummānu.6

Sennacherib took control of Babylon, entered Merodach-Baladan’s palace, and took both plunder and prisoners:

With a rejoicing heart and a radiant face, I rushed to Babylon and entered the palace of Marduk-aplaiddina (II) (Merodach-Baladan II) to take charge of the possessions and property therein. I opened his treasury and brought out gold, silver, gold (and) silver utensils, precious stones, beds, armchairs, a processional carriage, royal paraphernalia of his with gold (and) silver mountings, all kinds of possessions (and) property without number, a substantial treasure, (together with) his wife, his palace women, female stewards, eunuchs, courtiers, attendants, male singers, female singers, palace servants who cheered up his princely mind, all of the craftsmen, as many as there were, (and) his palace attendants, and I counted (them) as booty.7

The Assyrian king then set out after Merodach-Baladan, who had hidden himself in the swamps of Guzummānu, but could not find him. It appears that Merodach-Baladan died while in exile and never again regained the throne of Babylon.

Merodach-Baladan in the Bible

Merodach-Baladan’s brief appearance in the Bible seems to be steeped with intrigue. When he heard that King Hezekiah had been sick to the point of death but had recovered, the Babylonian king sent envoys with letters and a gift to the Judahite king (Isa 39:1). The timing of this event is interesting. According to Isaiah, Hezekiah’s sickness and healing occurred “in those days,” alluding to Sennacherib’s invasion in the preceding chapters. Merodach-Baladan’s embassy may have been during his brief second reign, or just before it as he was preparing to retake the Babylonian throne.8

Set against the geopolitical backdrop of Assyrian aggression, it is not a stretch to believe there was more to this visit than just well-wishes on Hezekiah’s recovery. Gordon Franz suggests plausible ulterior motives to the overtures of the Babylonian king: “Apparently Merodach-Baladan was either proposing to have a two-front revolt against the Assyrians, he on the eastern end of the empire and Hezekiah on the western end, or he was assessing the assets of Hezekiah, and the feasibility of a future revolt.”9 It is, admittedly, speculation to posit such ulterior motives. However, it fits so well within the geopolitical situation of Assyria’s aggression, especially with Merodach-Baladan and Hezekiah sharing a common foe, that many scholars believe the Babylonian king was reaching out to seek an alliance with Judah against Sennacherib.

Conclusion

One of the great services of archaeology to the field of biblical studies is the way in which it illuminates events in biblical history. In the case of Merodach-Baladan, though we know little about his 12-year reign, the Babylonian and Assyrian records contain numerous references to his conflict with Assyria. This provides the historical backdrop to the intriguing visit of his envoys to King Hezekiah, and provides potential explanations for plausible ulterior motives.

Cover Image: Boundary Stone of Merodach-Baladan. Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Endnotes:

1 Royal Inscriptions of Babylonia. Online: https://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/ribo/Q006305?list=withatf (Accessed Feb. 14, 2025).

2 Mordecai Cogan, The Raging Torrent: Historical Inscriptions from Assyria and Babylonia Relating to Ancient Israel. (Jerusalem: Carta, 2015), 147.

3 Cogan, 144.

4 A.K. Grayson, Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles. (Locust Valley, New York: J.J. Augustin Publisher), 75.

5 Grayson, 75.

6 A. Kirk Grayson and Jamie Novotny, The Royal Inscriptions of Sennacherib, King of Assyria (704–681 BC), Part 1. (Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 2012), 32–34.

7 Grayson and Novotny, 32–34.

8 Donald J. Wiseman, Tyndal Old Testament Commentaries: 1 and 2 Kings. (Nottingham: Inter-Varsity Press, 1993), 280.

9 Gordon Franz, “The Hezekiah-Sennacherib Chronology Problem Reconsidered – Chapter 4.” Online: https://www.lifeandland.org/2011/02/883/ (Accessed Feb. 14, 2025).