In my new series, “Letters from the Biblical World,”I am exploring extra-biblical letters from the ancient Near East that appear to reference or illuminate events described in the Bible. In my first post, I analyzed the Amarna Letters. In this post, I will be studying the Lachish Letters.

Where is Lachish?

Lachish is identified with Tell ed-Duweir, now called Tel Lachish, a proposal made by Albright and affirmed through numerous archaeological discoveries.1 Lachish was first settled in the Neolithic period, but grew to become a prominent Canaanite city, and later an important Judahite city. Lachish is located in the Judean foothills, approximately 25 miles (41 km) southwest of Jerusalem. In ancient times, the Via Maris, the main coastal highway, ran past the city, giving Lachish a strategic location along an important trade route. Lachish is perhaps best known for the siege that Sennacherib, king of Assyria, laid against her in 701 BC (2 Chr 32:9). The remains of the siege ramp, Assyrian arrowheads, and depictions of the fall of Lachish from the walls of Sennacherib’s palace have all been unearthed through archaeological excavations. After its destruction by the Assyrians, Lachish lay abandoned for a period of time before being rebuilt, albeit on a smaller scale, probably during the reign of Josiah (ca. 639–609 B.C.).2 It was again destroyed by the Babylonian army of Nebuchadnezzar in 587/6 BC.3

What are the Lachish Letters?

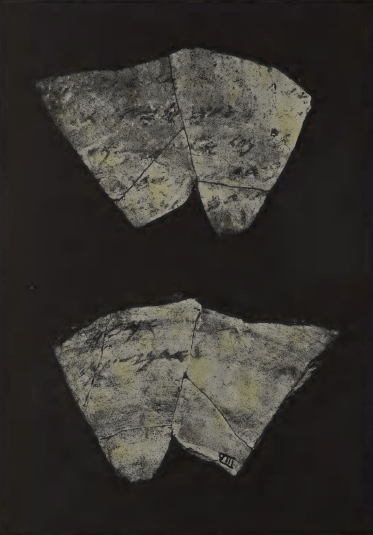

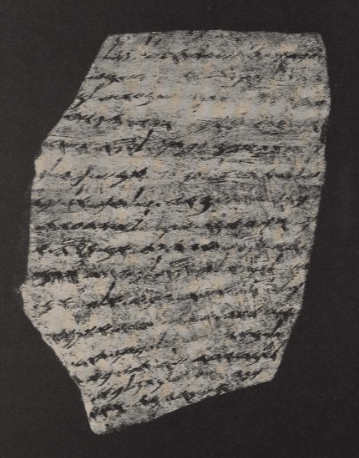

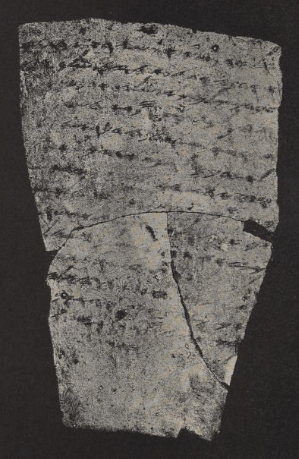

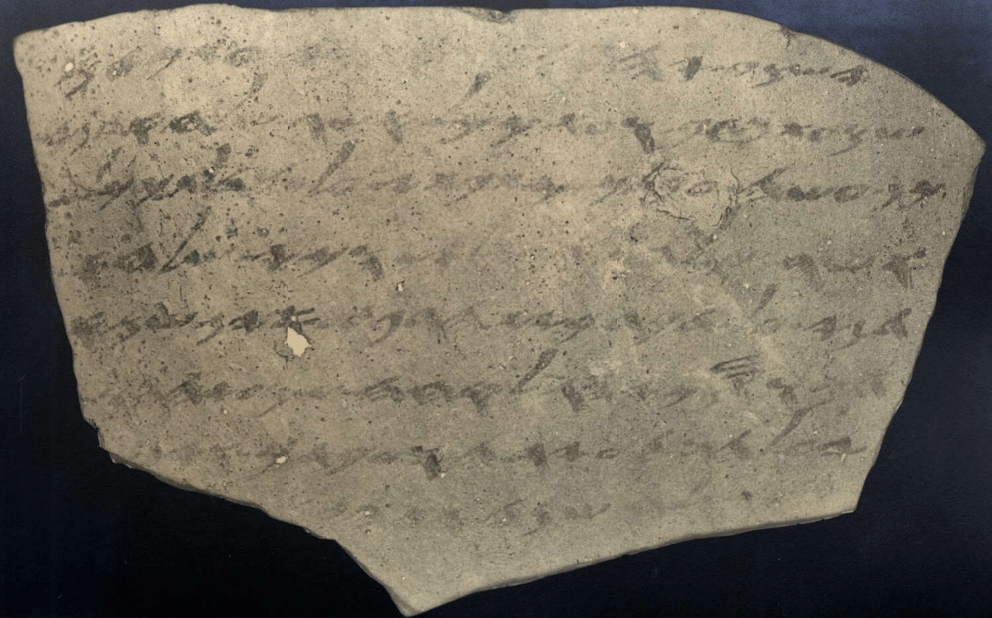

The Lachish Letters are a collection of 21 ostraca that was discovered by J.L. Starkey between 1935 and 1938 in the burned remains of the city’s gate complex. An ostracon (pl. ostraca) is a pottery sherd with writing on it. These ostraca are primarily letters containing military reports and discussions of affairs in the kingdom. As such, they provide a revealing glimpse into everyday life in Judah just before the Babylonian invasion. Since the letters only present one side of the conversation, determining the exact context can sometimes prove difficult. Of the 21 letters, three are addressed to “my Lord Yaush” (II, III, and VI), although at least three others (IV, V, and VII) seem to be sent to this same individual. Yaush is usually identified as the military commander at Lachish. According to David Ussishkin, “The letters appear to have been sent by a subordinate stationed at some point where he could watch signals from Lachish and Azekah.”4

Lachish Ostracon XIII seems to give direction for the digging of a defense trench: “Stand up to do work and Semakhyahu shall dig it out….quivers.” Harry Torczyner, who published the first translation of the Lachish letters, suggests that the sentence might have read, “Stand up and do work [and prepare a trench for the defense]; Semakhyahu shall take care of the digging work, [while other men shall make ready or bring in bows and arrows and] quivers.”5

In Lachish Ostracon III, an official named Hoshaiah writes to Yaush to defend himself against the accusation that he cannot read. “And as for what my lord said, “Dost thou not understand?—call a scribe!”, as Yahweh liveth no one hath ever undertaken to call a scribe for me; and as for any scribe who might have come to me, truly I did not call him nor would I give anything at all for him!”6 This provides evidence of a certain level of literacy within the kingdom of Judah at that time. Moreover, Hoshaiah is a biblical name known from this period (Jer. 42:1), although it is not possible to know if they are the same person in each text.

The letters also contain information on the movement of various key people within the kingdom. In Ostracon IV, it is reported that Shemaiah had taken Semachiah up into the city, while Ostracon VIII mentions that Nedabiah had fled to the mountains.7

How do the Lachish Letters Relate to Biblical History?

Since the Lachish Letters were discovered in a destruction layer attributed to the Babylonians, and because there are numerous descriptions of this event in the Bible, it is natural to compare these two groups of ancient texts. There are some striking similarities.

Letter III refers to a prophet who warns the people of Judah: “And as for the letter of Tobiah, servant of the king, which came to Shallum son of Jaddua through the prophet, saying, “Beware!”, thy servant hath sent it to my lord.”8 The Bible records that, around this time, Jeremiah was proclaiming similar prophecies: “Beware the days are coming…” (Jer. 7:32 NIV); “Beware of your friends…” (Jer. 9:4 NIV); “Beware the days are coming…” (Jer. 19:6 NIV). Moreover, the book of Jeremiah records that he was not the only prophet saying such things. Jeremiah 26:20 records, “Now Uriah son of Shemaiah from Kiriath Jearim was another man who prophesied in the name of the LORD ; he prophesied the same things against this city and this land as Jeremiah did.” While the prophet in Lachish Letter III is unnamed, his message is consistent with those being proclaimed by biblical prophets at that time.

Letter VI appears to indicate that the warnings of the prophets in the land of Judah were having a demoralizing effect upon the people. It reads in part, “Read, I pray, the words of the [prophet] are not good, (liable) to loosen the hands, [to make] sink the hands of the coun[try and] the city.”9 The idea of loosing/sinking/weakening the hands seems to indicate that the populace or the defenders were dejected. The Bible records that Jeremiah’s prophecies had the same effect on the people. “Then the officials said to the king, ‘Let this man be put to death, for he is weakening the hands of the soldiers who are left in this city, and the hands of all the people, by speaking such words to them. For this man is not seeking the welfare of this people, but their harm’” (Jer. 38:4 ESV).

Letter III mentions an interesting development in the kingdom. “And it hath been reported to thy servant, saying, ‘The commander of the host, Coniah son of Elnathan, hath come down in order to go into Egypt; and unto Hodaviah son of Ahijah and his men hath he sent to obtain… from him.’”10 The reason the commander of the army went to Egypt is unknown and Hodaviah the son of Ahijah’s role in this is unclear. Torczyner believed this letter was referring to the events described in Jeremiah 26:20–23, when the prophet Uriah fled to Egypt for his life.11 “Then King Jehoiakim sent to Egypt certain men, Elnathan the son of Achbor and others with him, and they took Uriah from Egypt and brought him to King Jehoiakim, who struck him down with the sword and dumped his dead body into the burial place of the common people” (Jer. 23:22–23 ESV). One problem with this interpretation is that the Lachish Letters are usually dated to the reign of Zedekiah (ca. 597–586 BC), and the biblical event occurred during the reign of Jehoiakim (ca. 609–598 BC). Others, like Scott B. Noegel, suggest the commander of the army went to Egypt on a diplomatic mission to obtain military support against the Babylonians.12 According to Jeremiah 37:5–7, the Egyptian army under Pharaoh Hoprha/Apries did come to the aid of Judah, although it provided only a temporary reprieve.

Lachish Letter IV contains a seemingly dramatic statement: “And let (my lord) know that we are watching for the signals of Lachish, according to all the indications which my lord hath given, for we cannot see Azekah.”13 If this letter is indeed being written from an official at an outpost to the commander of Lachish, it could indicate that writer was watching the Babylonian invasion unfold before his eyes. According to this line of reasoning, the signal fires of Azekah had gone out because that city had fallen to the Babylonians, and the writer was watching for the signal fires of Lachish to see if that city had fallen too. This fits well with Jeremiah’s testimony: “When the army of the king of Babylon was fighting against Jerusalem and against all the cities of Judah that were left, Lachish and Azekah, for these were the only fortified cities of Judah that remained” (Jer. 34:7 ESV). Others suggest the statement in Letter IV should be interpreted geographically, that is, that the writer was at a fortress that did not have a clear line of sight to Azekah.

While I have focused on the commonly accepted interpretations of the Lachish Letters, I should note that there are a host of others. For example, Yigal Yadin suggested the ostraca were drafts of letters composed at Lachish and sent to Jerusalem on papyrus.14 Anson Rainey countered Yadin’s arguments suggesting the original theory of their composition was likely correct, namely that “Hosha’yahu was writing to Ya’ush at Lachish. Hosha’yahu affirmed that he was watching out for the fire signals of Lachish according to the code set up by Ya’ush.”15

Finally, I should note another ostracon from Lachish, which was discovered in 2016 and published this year (2025).16 While this was not found in the city gate complex, it was discovered on the northern slope in Level II which was destroyed by the Babylonians in the sixth century BC. The ink on the ostracon was faded, but was readable in part when scanned by a hyperspectral camera. The clearest line read, “On the 1[6?] (day of the month) Špn son (of)…”17 A man named Špn, (Shaphan in English), is listed in 2 Kings 22:2 as an official in the court of King Josiah. A bulla (seal impression) from the time of Jeremiah bearing the inscription, “Belonging to Gemariah, son of Shaphan” was discovered in the “House of Bullae” in the City of David excavations in the 1980’s by Yigal Shiloh.18 While it is impossible to conclusively say the newly discovered ostracon from Lachish refers to the biblical Shaphan or one of his descendants, it does demonstrate that the name was in use around the time the Bible indicates.

Conclusion

The Lachish Letters highlight an important period in the history of the kingdom of Judah. They provide archaeological evidence of the military, administrative, and political situation in Judah just before the Babylonian invasion in 587/86 BC. This period is also described poignantly in the book of Jeremiah. At many points, the Lachish letters corroborate and illuminate the biblical description of the fall of the kingdom of Judah.

Cover Photo: Lachish Letter II / © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license

Endnotes:

1 David Ussishkin, “Lachish.” In The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. D.N. Freedman. (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 5019.

2 Ussishkin, 5028.

3 For a discussion of whether Jerusalem fell to the Babylonians in 586 or 587 BC, see Roger Young’s article, “When Did Jerusalem Fall?” JETS 47/1 (March 2004) 21–38. Online: http://www.rcyoung.org/articles/jerusalem.html (Accessed Aug. 26, 2025).

4 David Ussishkin, “Lachish.” In The New Encylopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land – Vol. 3. Ed. Ephraim Stern. (Jerusalem: Carta, 1993)., 910.

5 Harry Torczyner, The Lachish Letters I (London: Oxford University Press, 1938), 159.

6 James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1969), 322.

7 Pritchard, 322.

8 Prichard, 322.

9 Harry Torczyner, The Lachish Letters I (London: Oxford University Press, 1938), 117.

10 James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1969), 322.

11 Harry Torczyner, The Lachish Letters I (London: Oxford University Press, 1938), 64–67.

12 Scott B. Noegel, “The Lachish Ostraca.” In The Ancient Near East: Historical Sources in Translation, ed. Mark W. Chavalas. (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2006), 402.

13 James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1969), 322.

14 Yigal Yadin, ‘The Lachish Letters – Originals of Copies and Drafts?’, In Recent Archaeology in the Land of Israel, ed. H. Shanks.(Washington: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1984), 179-86.

15 Anson F. Rainey, “Watching Out for the Signal Fires of Lachish.” Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 119:2 (1987), 151.

16 Daniel Vainstub, Hoo-Goo Kang, Barak Sober, Iris Arad, and Yosef Garfinkel, “A New Hebrew Ostracon from Lachish.” Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology 8 (2025), 41–50.

17 Vainstub et al, 46.

18 Nahman Avigad and Benjamin Sass. Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals. (Jerusalem:

The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Israel Exploration Society, and

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, The Institute of Archaeology, 1997), p. 191 (No. 470).