“On the third day Esther put on her royal robes and stood in the inner court of the king’s palace, in front of the king’s quarters, while the king was sitting on his royal throne inside the throne room opposite the entrance to the palace. And when the king saw Queen Esther standing in the court, she won favor in his sight, and he held out to Esther the golden scepter that was in his hand. Then Esther approached and touched the tip of the scepter. ” (Esth 5:1–2).

The image of Queen Esther bravely entering the presence of the King of Persia unsummoned is one of the Old Testament’s most powerful and endearing scenes. Her uncle, Mordecai, had urged her to approach the king and plead for the salvation of the Jewish people. He reasoned with her, saying, “For if you keep silent at this time, relief and deliverance will rise for the Jews from another place, but you and your father’s house will perish. And who knows whether you have not come to the kingdom for such a time as this?” (Esth 4:14).

Many scholars today regard the Book of Esther as a work of fiction, viewing it as nothing more than an inspiring court tale. However, the author presents the events in a straightforward, historical way. Also, the book contains no miracles—one of the general reasons often cited for questioning the Bible’s authenticity. Some supposed discrepancies between the Bible and other historical sources have been used to challenge the book’s reliability. For example, the Book of Esther mentions 127 Persian provinces (Esth 1:1), while Herodotus describes only twenty.1 However, the Greek word satrapeia used by Herodotus may not be equivalent to the Hebrew word medinah used in the Bible, suggesting a possible difference in administrative divisions rather than a contradiction. Scholars like Jon D. Levenson cite Herodotus that Persian kings could only marry within seven noble families as another historical inaccuracy.2 But, according to Herodotus, Xerxes’ wife, Amestris, was not from one of the seven noble families, so there could apparently be exceptions to this rule.3

After studying the archaeology of the period, I find no clear, unexplainable contradictions between the Book of Esther and known history. Rather, archaeology and other ancient writings support many of the general details recorded in the biblical text. While Esther herself has not been identified, nor has the plot to destroy the Jewish people been confirmed, the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Many events described in ancient records remain unverified by archaeology.

Persian scholar Edwin Yamauchi has carefully examined the Book of Esther and concludes that it was likely written early in the Persian era.4 He argues that it is more reasonable to take the book at face value as a historical narrative rather than relying on speculative theories about its composition.5

Here are the top ten discoveries related to the Book of Esther.

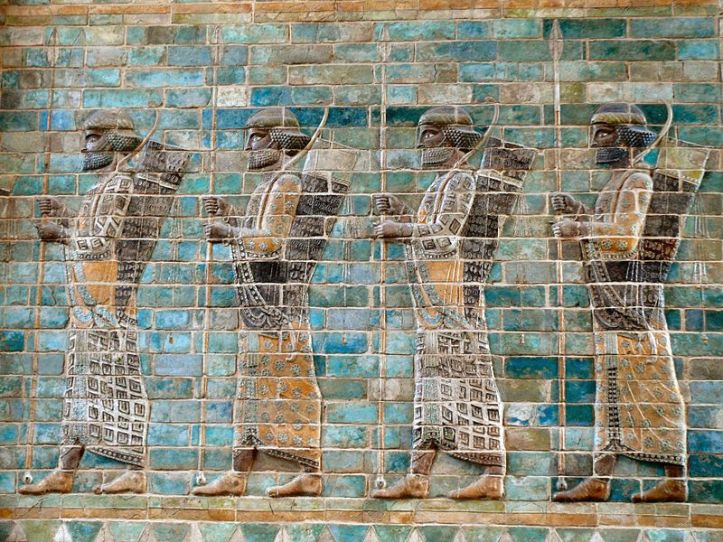

10. Reliefs of King Xerxes

“Now in the days of Ahasuerus, the Ahasuerus who reigned from India to Ethiopia over 127 provinces, in those days when King Ahasuerus sat on his royal throne in Susa, the citadel, in the third year of his reign he gave a feast for all his officials and servants” (Esth 1:1-3).

Ahasuerus is better known in history by his Greek name, Xerxes. His Hebrew name, Ahasuerus, likely derives from the Akkadian Ahsiarsu, while in Old Persian, his name was Khsayarsan.6 Numerous reliefs of King Xerxes remain, both at Persepolis and on his tomb at Naqsh-e Rustam. Persepolis was one of the ancient Persian capitals, along with Susa, Ecbatana, and Babylon. One of the most famous reliefs from Persepolis is the Treasury Relief, which once adorned the southern wall of Courtyard 17.7 It depicts a Persian king seated on a throne with the crown prince standing behind him, identified as King Darius I and his son, Xerxes.8 After ruling Persia for twenty years, Xerxes was assassinated by a bodyguard and was buried in the rightmost of the four tombs at Naqsh-e Rustam. A relief of Xerxes was carved into the upper panel of the façade. These depictions of Xerxes provide readers of the Book of Esther with vivid images of the biblical King Ahasuerus.

9. Persian Drinking Vessels

“Drinks were served in golden vessels, vessels of different kinds, and the royal wine was lavished according to the bounty of the king” (Esth 1:7).

The Persians were renowned for their extravagant banquets and, in particular, for drinking wine from splendid vessels.9 For example, Herodotus describes Persian tents filled with “golden bowls and cups and other drinking vessels,” while on their campaign against the Greeks.10 Thus, the biblical description of this detail aligns well with other historical accounts of Persian customs. Numerous examples of Persian drinking flagons, called rhytons, which were used at royal banquets have been discovered. These vessels often consisted of a horn-shaped cup with a decorative animal head extending outward from the bottom, serving as a handle.

8. Harem at Persepolis

“And let the king appoint officers in all the provinces of his kingdom to gather all the beautiful young virgins to the harem in Susa the citadel, under custody of Hegai, the king’s eunuch, who is in charge of the women. Let their cosmetics be given them” (Esth 2:3).

The harem (literally the “house of the women”) refers to the quarters where the royal queens and concubines of the Persian kings resided. At Susa, archaeologists have identified a series of rooms in the southwestern part of the palace, just south of the King’s Apartment, as the harem or “women’s quarters.”11 This area consisted of five identical apartments, each about 800 m² in size, with several smaller rooms, sanitation facilities, and a ceremonial space.12 While this area was excavated, it had suffered heavily from erosion and little can be seen there today.

In contrast, the harem of Xerxes at Persepolis is much better preserved and provides insight into the lives of Persia’s royal women. The main section featured a central hall and a portico that opened onto a garden, with stone reliefs of the king adorning the walls.13 The living quarters for the royal women included a columned main room with one or more smaller adjacent chambers. Some of the bell-shaped column bases were discovered in situ.14 The Harem of Xerxes at Persepolis has been reconstructed and now serves as a museum at the site.

7. Head of a Persian Queen

“The king loved Esther more than all the women, and she won grace and favor in his sight more than all the virgins, so that he set the royal crown on her head and made her queen instead of Vashti” (Esth 2:17)

Herodotus records that the chief wife of Xerxes was named Amestris, 15 which can be linguistically linked to the name Vashti.16 Bible scholar, William Shea, has harmonized the chronology of Herodotus and the Book of Esther, demonstrating that the Greek historian’s account only covers the first 7 years of Xerxes’ reign.17 There is no record of who Xerxes’ chief wife was from the seventh year to the end of his reign. This is precisely the timeframe that Esther was crowned queen of Persia according to the biblical text.

The head of a Persian queen, discovered at Persepolis, is on display at the National Museum of Iran. It is carved out of lapis lazuli, is 6.6 cm tall, and portrays a queen wearing a crenellated crown. While the exact queen it depicts is not known with certainty, some scholars suggest it is Queen Atossa, the daughter of Cyrus the Great, the wife of Darius the Great and the mother of Xerxes.18 It provides a visual example from the Achaemenid period of the royal crown Queen Esther may have worn.

6. Persian Silver Coins

“If it please the king, let it be decreed that they be destroyed, and I will pay 10,000 talents of silver into the hands of those who have charge of the king’s business, that they may put it into the king’s treasuries” (Esth 3:9).

Haman promised to pay an immense amount of silver into the king’s treasuries if the king consented to the destruction of the Jewish people within the empire. But what would this payment have looked like?

Coins were introduced to Persia after Cyrus the Great conquered Lydia, the birthplace of coinage.19 However, it was Darius I who standardized and expanded the use of gold darics and silver sigloi throughout the empire’s economic system. These coins often depicted a crowned Persian hero or king running while holding a spear and a bow on the obverse, with a rectangular punch mark on the reverse.20

Given the size of Haman’s intended payment, much of the silver would likely have been in the form of bullion. He may also have planned to use the plundered wealth of the Jewish population in Persia to fulfill his pledge, meaning the payment could have included a large number of silver coins as well.

5. Pur (Dice)

“In the first month, which is the month of Nisan, in the twelfth year of King Ahasuerus, they cast Pur (that is, they cast lots) before Haman day after day; and they cast it month after month till the twelfth month, which is the month of Adar” (Esth 3:7).

The practice of casting pur is documented in ancient Akkadian texts. The Hebrew word for “cast” is nâphal, which derives from a root meaning “to fall.” The word pur, meaning “lot,” likely comes from the Akkadian term pūru. The ancient Assyrians used to cast pur to make decisions. For example, Shalmaneser III recorded, “In my thirty-first regnal year, (when) I threw the die (pūru) for a second time before the gods Aššur (and) Adad…”21 An Assyrian pūru—a small clay cube inscribed with cuneiform identifying it as the lot of Yahali—is housed in the Yale Babylonian Collection.22 Haman likely cast a similar small clay die to determine the date for the destruction of the Jewish people. One can imagine his frustration when the result was a date 11 months in the future.

4. Marduka Tablets

“For Mordecai was great in the king’s house, and his fame spread throughout all the provinces, for the man Mordecai grew more and more powerful” (Esth 9:4).

Mordecai’s name is likely derived from Marduk, the chief god of Babylon, and means, “Man of Marduk.”23 It was not unheard of for Jews living in the land of exile to have been given names that honored pagan gods. For example, Daniel was known by the name Belteshazzar (meaning “Bel’s prince”) throughout his time in Babylon, spanning the reigns of Nebuchadnezzar, Belshazzar, and Cyrus (see Dn 1:7; 2:26; 4:9; 5:12; 10:1).

The name Mordecai corresponds to Marduka, a name attested in Persian records. In 1934 and 1935, excavators at Persepolis unearthed 30,000 Elamite tablets and fragments dating from the 13th to the 28th year of Darius I’s reign (509–494 BC). Among this collection, known as the Persepolis Fortification texts, there are more than thirty references to the name Marduka, which may correspond to up to four different individuals.24 Edwin Yamauchi concludes, “Though we cannot be certain, it is possible that one of these may have been the biblical Mordecai.”25

3. Darius’ Foundation Deposit from Palace at Susa

“And when these days were completed, the king gave for all the people present in Susa the citadel, both great and small, a feast lasting for seven days in the court of the garden of the king’s palace. There were white cotton curtains and violet hangings fastened with cords of fine linen and purple to silver rods and marble pillars, and also couches of gold and silver on a mosaic pavement of porphyry, marble, mother-of-pearl and precious stones” (Esth 1:5-6).

The setting for the Book of Esther and the lavish banquet recorded in the first chapter is the palace at Susa. It was constructed by Darius I and served as the winter residence for the Persian kings. A foundation deposit from the palace has been discovered, inscribed in three languages: Old Persian, Akkadian, and Elamite. This inscription, known as DSf, also provides an extravagant description of the palace:

“The palace which I built at Susa, from afar its ornamentation was brought…the cedar timber, this – a mountain named Lebanon – from there was brought…The gold was brought from Sardis and from Bactria, from here was wrought. The precious stone lapis-lazuli and carnelian which was wrought here, this was brought from Sogdiana. The precious stone turquoise, this was brought from Chorasmia, which was wrought here. The silver and the ebony were brought from Egypt. The ornamentation with which the wall was adorned, that from Ionia was brought. The ivory which was wrought here, was brought from Ethiopia and from Sind and from Arachosia. The stone columns which were wrought, a village by name Abiradu in Elam – from there were brought. The stone-cutters who wroght the stone, those were Ionians and Sardians….Saith Darius the King: At Susa a very excellent work was ordered, a very excellent work was brought to completion.26

The foundation inscription of Darius closely resembles the opulent description of the palace recorded in Esther 1:5-6

2. Reliefs from the Outer Courtyard

“And the king said, “Who is in the court?” Now Haman had just entered the outer court of the king’s palace to speak to the king about having Mordecai hanged on the gallows that he had prepared for him” (Esth 6:4)

The palace at Susa featured three courtyards: the outer (eastern) court, the central court and the inner (western) court. The largest of these was the outer courtyard, which covered 3500 m2. It was accessed through a chambered gateway flanked by statues, though only the supporting bases remain today.27 The walls around the courtyard were decorated with glazed brick friezes depicting the famous Persian soldiers called “The Immortals.” The inner courtyard, also known as the Honor Court, was smaller, measuring only 1000 m2. Above its entrance was a mural of glazed bricks, featuring lions, winged bulls, sphinxes, and griffins.28 Many of these reliefs have been reconstructed from the excavated glazed bricks and are now displayed at the Louvre Museum. These very images would have been seen many times by Ahasuerus, Esther, Mordecai, and Haman as they passed through the palace.

1. The Floorplan of the Palace at Susa

“On the third day Esther put on her royal robes and stood in the inner court of the king’s palace, in front of the king’s quarters, while the king was sitting on his royal throne inside the throne room opposite the entrance to the palace” (Esth 5:1)

French archaeologists excavated at Susa intermittently from 1897 to 1979. Thanks to their efforts, the palace at Susa has been significantly studied and preserved. Their findings have demonstrated that the author of the Book of Esther was intimately familiar with the palace’s layout. The descriptions of specific rooms and locations in the biblical text align remarkably well with what has been uncovered through archaeological excavations. The details in the Book of Esther are so precise that one can identify the exact places where key events occurred using a simple Google Earth image of the palace:

- The Audience Hall/Court of the Gardens where Xerxes’ banquet took place (Esth 1:5)

- The King’s Gate where Mordecai sat (Esth 2:19)

- The Harem where Esther and the other young ladies stayed (Esth 2:3)

- The Inner Courtyard facing the Throne Room, where Esther prepared to enter the king’s presence. (Esth 5:1a)

- The Throne Room where Esther approached Ahasuerus unsummoned (Esth 5:1b)

- The Outer Courtyard where Naman waited to speak to the king (Esth 6:4)

Jean Perrot, who led the excavations at the palace at Susa from 1969 to 1979 concluded that there is no doubt the author of the Book of Esther possessed “a knowledge of the arrangement of the royal palaces of the period and the customs of the Achaemenid court.”29

Conclusion

Ultimately, the Book of Esther purports to provide the historical background to the Feast of Purim (Esth 9:21–28), which derives its name from the fact that Haman cast the pur to try and destroy the Jewish people (Esth 9:26). Even today, many Jewish people in Israel and around the world celebrate their deliverance through the Feast of Purim.

Bible scholar Karen H. Jobes, whose commentary on Esther is consistently listed as one of the best, notes:

Christianity and its parent, Judaism, consciously rest on the concept that God has in fact worked in history through events that really happened. Judaism and Christianity rest not on the inward, mystical journey of the mind and soul of the individual, but on events in history through which the Creator-Redeemer God revealed himself to people. Biblical narratives such as Esther are the record of those events in the form of story. Purim would be a hollow religious celebration if the Jews in Persia had not truly been delivered from destruction.30

These ten discoveries related to the Book of Esther help readers visualize and contextualize the narrative while also confirming specific details in the Bible. Moreover, other features in the biblical text suggest it was written early and accurately records authentic Persian cultural elements. For example, thirty personal names and twelve Persian loan words in the Book of Esther are attested in other early Persian texts.31 All of this leads me to conclude that the most plausible explanation for the Book of Esther is that it accurately records actual events that took place during the reign of Xerxes and provides the historical basis for the Jewish Feast of Purim.

Postscript: I wish to acknowledge the assistance of Todd Bolen from BiblePlaces.com, who made several helpful suggestions. His Photo Companion to the Bible: Esther, was a great resource as I prepared this blog and I highly recommend it! You can purchase it here: https://www.bibleplaces.com/esther-photo-companion-to-the-bible/

Cover Image: Esther Before Ahasuerus, 1862 Engraving from The Popular Pictorial Bible, Containing the Old and New Testaments / Public Domain

Endnotes:

1 Herodotus, Histories, 3.89. Online: https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Herodotus/3D*.html#89 (accessed March 3, 2025).

2 Jon D. Levenson, Esther: A Commentary. (London: Westminster Jon Knox Press, 1997), 24.

3 Edwin Yamauchi, Persia and the Bible. (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1990), 233.

4 Yamauchi, 228.

5 Yamauchi, 239.

6 Yamauchi, 187.

7 Erich F. Scmidt, Persepolis I: Structures, Reliefs, Inscriptions. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953), 162.

8 Schmidt, 163.

9 Edwin Yamauchi, Persia and the Bible. (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1990), 229.

10 Herodotus, Histories, 9.80.1

11 Jean Perrot, ed. The Palace of Darius at Susa. (London: I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd, 2013), 196.

12 Perrot, 234.

13 Erich F. Schmidt, Persepolis I: Structures, Reliefs, Inscriptions. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953), 257.

14 Schmidt, 258.

15 Herodotus, Histories, 7.114

16 William H. Shea. “Esther and History.” Andrews University Seminary Studies (AUSS) 14.1 (1976), 266–237.

17 Shea, 237– 241.

18 “Statue Atossa,” IUVM Archive. Online:https://iuvmarchive.org/en/image/statue-atossa-national-museum-of-iran (Accessed March 6, 2025).

19 Michael Alram, “The Coinage of the Persian Empire.” In The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage. Ed. William E. Metcalf (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 62–64.

20 Ben Wallace, “NGC Ancients: Coins of the Achaemenid Empire,” May 16, 2025. NGC Coins. Online: https://www.ngccoin.com/news/article/11633/NGC-Ancients-Achaemenid-Empire/ (Accessed March 6, 2025).

21 A. Kirk Grayson, Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC, Part II: 858-745 BC (Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia – Assyrian Periods 3); Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996), p. 70.

22 “Lot of Yahali,” Yale Peabody Museum. Online: https://collections.peabody.yale.edu/search/Record/YPM-BC-021122 (Accessed March 6, 2025).

23 David J.A. Clines, “Mordecai.” In The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. D.N. Freedman. (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 6114.

24 Edwin M. Yamauchi. “Mordecai, the Persepolis Tablets, and the Susa Excavations.” Vetus Testamentum, vol. 42, no. 2, 1992, pg. 273. Online: JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1519506 (Accessed March 7, 2025).

25 Yamauchi, 273.

26 Edwin M. Yamauchi, Persia and the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1990), 296.

27 Jean Perrot, ed. The Palace of Darius at Susa. (London: I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd, 2013), 226.

28 Perrot, 229.

29 Perrot, 475.

30 Karen H. Jobes, The NIV Application Commentary: Esther. (Grand Rapids, Zondervan, 1999), 42

31 Edwin Yamauchi, Persia and the Bible. (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1990), 237–238 .